I’m not entirely sure what happened.

It was the 30th nightly protest in downtown Montreal and I met up with thousands of protesters on the corner of Sherbrooke St. and University St. around 9:15 p.m. I carried a backpack with me, crammed with pieces of identification, extra water bottles, scarves and bandages in case things turned ugly. Except Wednesday was energetic and peaceful, and I wasn’t worried to be out on the streets reporting. It was hot out; protesters clanging pots and pans marched without incident through the downtown core.

This has become the norm in Montreal. Quebec’s tuition crisis has been a three month long affair and complex to say the least. A sea of red squares can be found on every street corner, every city bus in Montreal and beyond into the outskirts of the city. The iconic red square has been seen on Saturday Night Live on the shirts of Arcade Fire, in France at Cannes and even on individuals in Chicago and western Canada. The student movement has grown into societal discontent among more than just students, it’s spread to labour unions, older generations, families, lawyers, artists and citizens in general.

It’s sneaked its way into the homes of individuals on a worldwide scale, transcending international borders and divides. On May 22, various cities held demonstrations and events in solidarity with Quebec’s student protests. Outside the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, hundreds congregated to voice their discontent with the Charest government. The Occupy Wall Street Movement in New York City has come out in support of the students, holding their own protests in several areas of the city.

But the crisis coupled with the historic, controversial and questionable Bill 78 has created an environment of tension and backlash. People from all sides are tired; the government, students, protesters, police officers and citizens all caught up in what seems to be an endless and exhausting crisis.

On that Wednesday night, after three hours of following separate protests calmly move through the streets, the atmosphere changed within a matter of seconds. Marching south on St-Denis St., I was tweeting and snapping photos at the head of the protest when I spotted a line of police officers waiting on Sherbrooke – and a massive gathering of countless riot cops standing behind them. A tiny bit of apprehension gnawed at me; a warning sign.

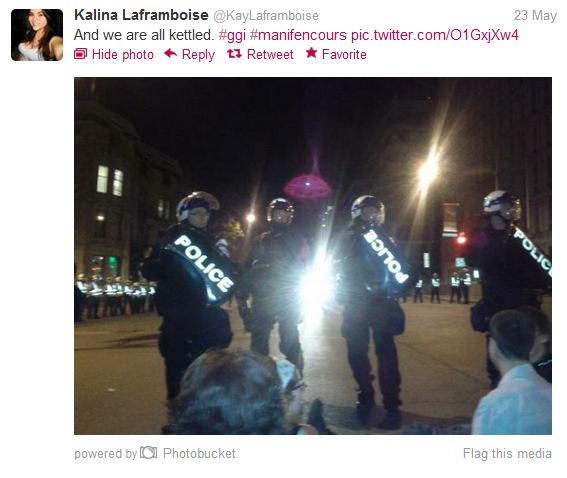

It happened so quickly. A weird standoff between police and protesters started and ended within five minutes. Protesters would charge, attempting to break through the line and the police would quickly respond in the same matter, sending dozens of students running in different directions. I tried to leave by going west on Sherbrooke but was met with an additional line of blue uniforms and shields. An officer not much older than me told me to move back into the middle.

Kettled. Kettling is a riot tactic that controls protesters by limiting them to a small area as police move in from all sides. It’s controversial because it forces everyone, including bystanders and law-abiding citizens, into detention and prevents them from leaving. In 2010, this crowd control method was used at the G20 summit in Toronto, enclosing hundreds people of all ages to a confined space, drawing criticism from many and spurring Toronto police to ban further use of this tactic altogether. In Germany, kettling has been challenged several times in court and has been ruled as inhumane or unlawful in many cases.

I was forced into the middle as police approached from all sides while protesters chanted in unison to remain calm and peaceful. This is a perfect example of a disadvantage of being a student journalist. We’re young. We’re students. And we’re not properly accredited. Therefore it’s difficult to be differentiated as a journalist rather than a protester. I’ve come to learn that police don’t discriminate.

It’s kind of scary to be caught in the middle, waiting to know what you’re going to be charged with and if you can leave. Fortunately I found other student journalists and we were instructed through Twitter by Canadian University Press Quebec Bureau Chief Erin Hudson and the Montreal Police to present ourselves to constable Daniel Lacourcière. It was quick and I was surprised with how helpful the Montreal Police’s media have been with young journalists.

It’s surreal to be looked at with hard, blank expressions from both Montreal and provincial police like I’ve done something wrong just for doing my job. But I was ultimately released, along with a handful of other journalists. I had to present my press pass and submit pieces of identification, explaining that I was not participating but reporting. Demonstators looked confused, some asking why we were allowed to leave while they couldn’t. Some just wanted to use a bathroom but were met with little response, officers have an uncanny ability to remain stoic in a situation where emotions are so present they are almost tangible.

It was an illegal protest and we were warned that prosecution awaits if we are found in violation of the law. Over 500 arrests were made that night and we were lucky to leave.

I was escorted by two young Montreal Police officers, a firm grasp on my elbow, to a second point just outside of the kettle. I was held there for approximately ten minutes, where I was asked again for my press pass and identification in order to leave.

Once I was released, I walked through the McGill Ghetto in a daze, with a provincial police helicopter flying overhead, avoiding Sherbrooke where city buses waited to transport the detained. I’ve lived in this province all my life, and I can’t remember a time where I worried for the safety of everyone. I never thought the crisis would get to this point, but it’s escalated to the degree where it’s dangerous. It’s no longer just a student movement and I wonder where the answer to this problem lies.

And to be honest, I’m not entirely sure how this will end.