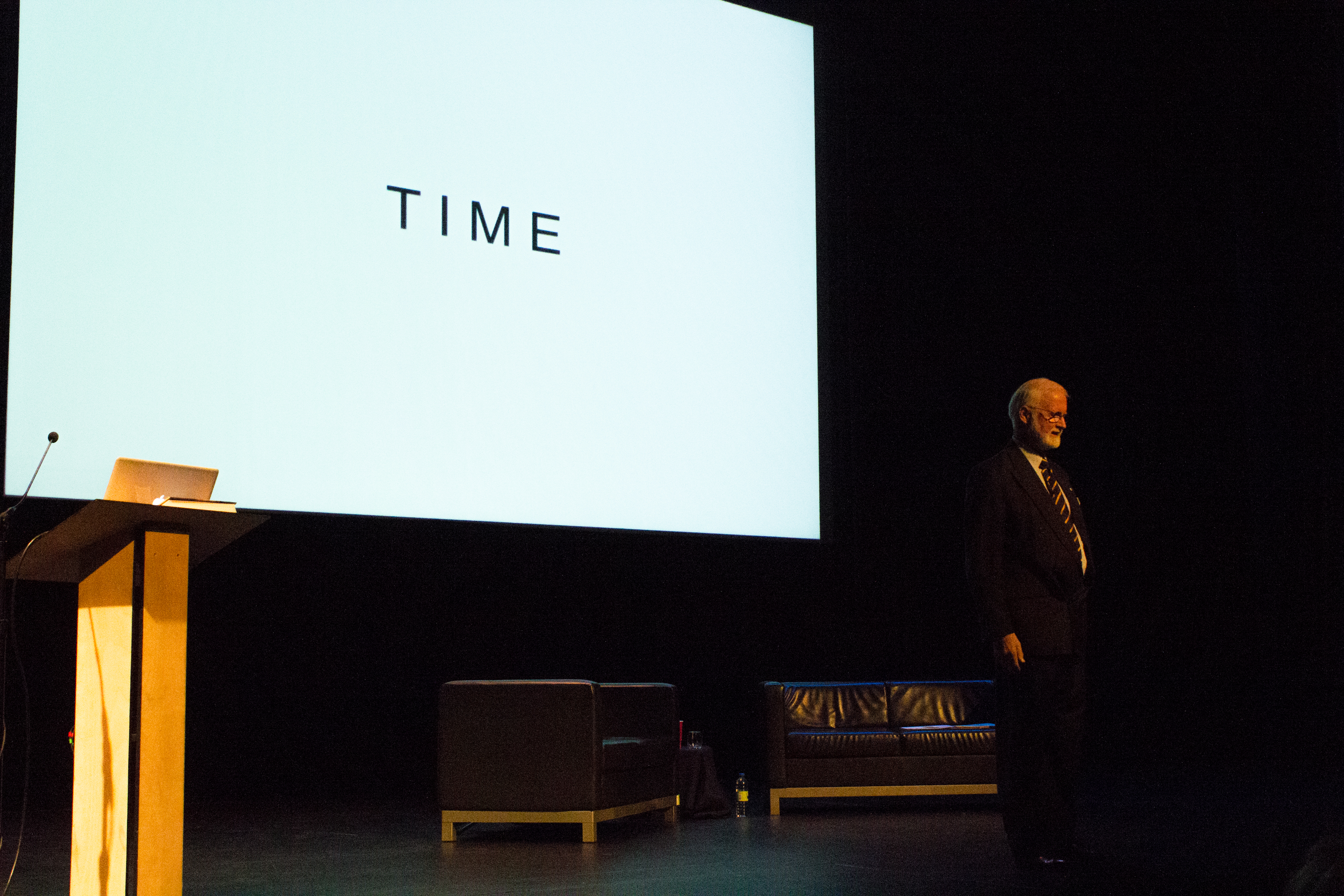

Former Canadian ambassador to the United Nations Robert Fowler discusses his “season in hell”

Canada’s former ambassador to the United Nations, Robert Fowler, spoke about his experience as a prisoner of the Al Qaeda terrorist group at Concordia’s DB Clarke theatre on Sept. 25.

In his presentation, “Sleeping with Al Qaeda,” Fowler discussed his 130-day experience of horror, as well as his thoughts on curbing radicalism, terrorism and violence in the regions of Africa where he was captured.

It was December 2008. Fowler, along with his colleague Louis Guay, were chosen by the United Nations’ secretary general to help defuse the tense political situation in Niger during a citizen-led rebellion against the government. Following a meeting with Niger’s president, Fowler and Guay were ambushed and captured by a group of radical terrorists, and smuggled into Mali. It was the start of what Fowler called “a season in hell.” Fowler would later go on to publish a book about this experience in 2011, which he titled Season In Hell: My 130 Days in the Sahara with Al Qaeda.

Fowler explained that he and Guay were considered prisoners of war, and were treated as such. They were hated. “Every moment was filled with fear,” said Fowler.

The men who captured Fowler and Guay were militant Salafist terrorists—conservative extreme radicalists who believe in violent jihadism. “[They] hated everything we stand for… our most cherished concepts of liberty, democracy, equality and free will,” said Fowler. “They were the most focused, most selfless, most single-minded and least horny group of young men I have ever encountered.”

In the depths of the Sahara Desert, Fowler experienced first-hand the mentality of these violent, extreme radicals. “The whole issue of free will is wrought with horror for them … In their view, nothing is man’s choice—it’s God’s choice … They wanted paradise. It didn’t matter when. If they died in jihad, it would be theirs.”

Fowler described a time during his imprisonment when he was assigned to a small area—the foot of a tree in the middle of a field, with a single guard keeping watch. The man was clearly upset—he was gnashing his teeth, pacing and mumbling angrily to himself. Eventually, the man thrust his gun in Fowler’s face and told him: “Just kill me, I want to go to paradise!”

After 130 days, the Malian and Canadian governments finally negotiated Fowler and Guay’s release. The “season in hell” came to an end, and Fowler said the experience convinced him these jihadists could not be reasoned with.

Despite this, Fowler doesn’t think all-out military action is the solution. “It is about diminishing the jihadi threat to the point the Africans can handle it. It is not about turning Niger into Alberta,” said Fowler. He cited the violence and poverty that continues to this day in areas like Mali and Niger as an example of how little Canada and the rest of the western world have done to help. “The Canadian senate published a paper called ‘Forty Years of Failure’ because we haven’t fixed Africa,” he said.

Fowler said he believes that the solution to the problems in Africa is to keep funding and supporting UN peacekeeping missions in areas where jihadism continues to cause problems. Fowler gave the example of the UN’s Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA). The mission consists of about 15,000 military personnel with a current budget of just under $1 billion. Rather than attacking with all-out force, MINUSMA carries out security-related tasks and helps defuse violent situations, while protecting and promoting human rights in Mali.

While Fowler has high hopes for programs like MINUSMA, he said he realizes that the conditions in places like Mali and Niger have not improved significantly since the time of his imprisonment. He recalled a time in the 60s, after he finished college, when nearly every one of his friends had traveled to culturally diverse countries like Niger. Nowadays, Fowler said, “it’s just too damn dangerous” for people to explore many parts of Africa.

Fowler’s discussion was the first in a series of speeches and panels organized by the Montreal Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies, titled “Assaulting Cultural Heritage: ISIS’s Fight to Destroy Diversity in Iraq and Syria.” The series was held at Concordia on Sunday, Sept. 25 and Monday, Sept. 26.