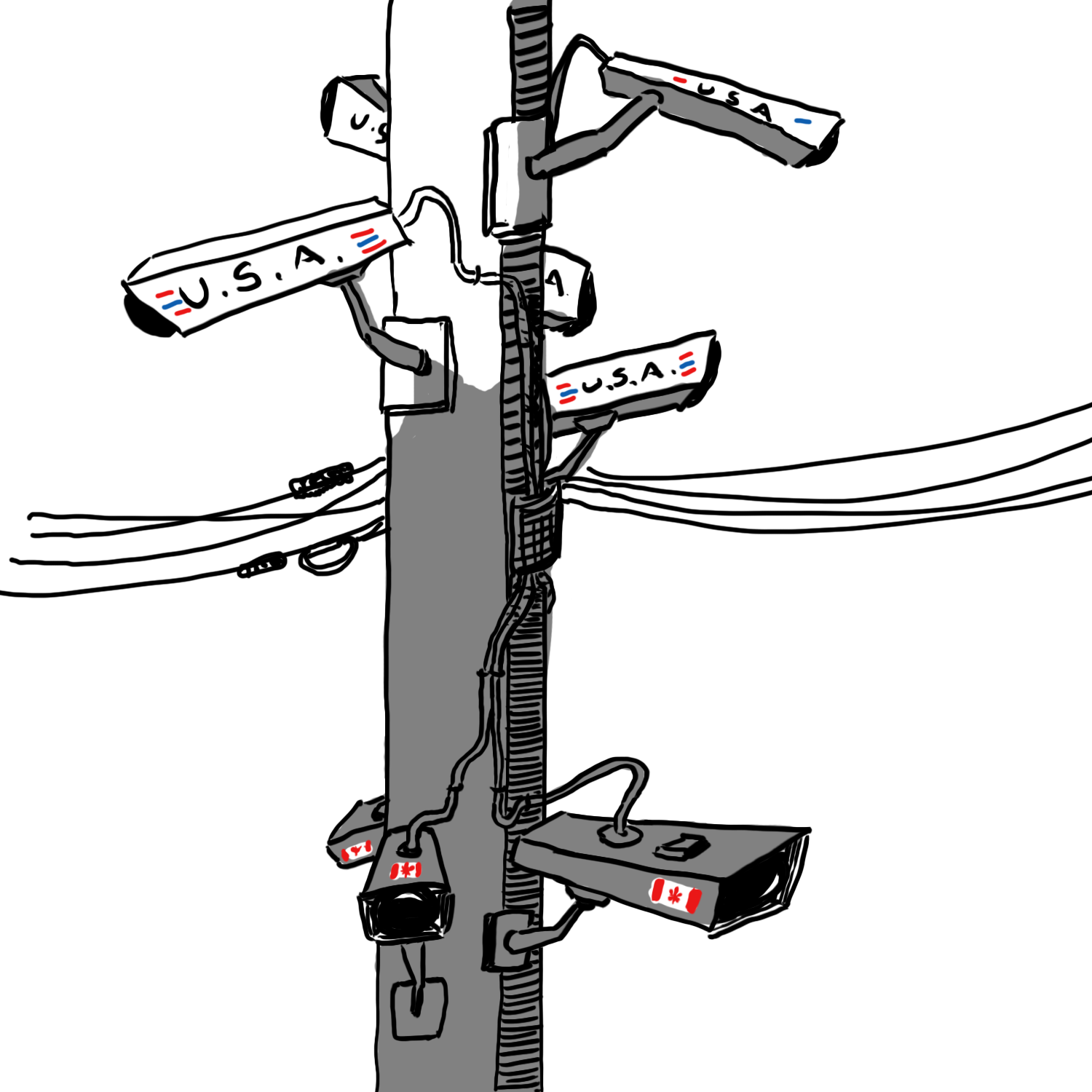

How Canada is quickly becoming a surveillance nation

It is not uncommon for us Canadians to compare ourselves to our American neighbours. Often, we consider ourselves better off, especially when looking at an issue like national surveillance and privacy concerns for the general population.

In May 2013, American whistleblower Edward Snowden fled to Hong Kong and published an array of classified documents, detailing the American government’s abuse of surveillance power. We scoffed at the unlawfulness of our neighbours to the south, yet are we really any better?

In the past few months alone, two cases of very controversial police action regarding surveillance in Canada were made public. These cases, both occurring in Montreal, have forced many, myself included, to question the power of the police as well as the amount of freedom we think we have.

At the end of October 2016, it became apparent that the mobile phone of La Presse journalist Patrick Lagacé was being tracked for several months prior, by the SPVM – unbeknownst to him – in an attempt to identify some of his sources. The 24 separate warrants the police issued allowed for them to legally conduct this highly controversial operation.

“The new powers that the police have to surveil Canadians are absolutely horrifying. They’re basically limitless, there’s very little oversight and, when that happens, the system will be ripe for abuse, and this is just an example of how it’s abused,” said Tom Henheffer, the executive director of Canadian Journalists for Free Expression (CJFE) in an interview with CBC News.

The other case occurred in September of last year, when Michael Nguyen, a journalist with the Journal de Montréal journalist had his computer seized by the Quebec provincial police, after they believed he hacked their website to obtain information about a judge’s abusive behaviour. Nguyen and George Kalogerakis—the managing editor of Le Journal—are strongly condemning the actions taken by the Quebec police via multiple interviews with the media.

“I can tell you that our reporter did not break any laws to get his story,” said Kalogerakis in an interview with the Toronto Star. “We do not break laws at the Journal. We will contest the validity of the search warrant as far as we can.”

It is completely unacceptable, in my opinion, for the police to conduct themselves in this unethical, privacy-breaching manner—not because I am a journalism student, but because I am a human being with morals. The worst part is the police’s actions in the two abovementioned instances were completely legal because they obtained permits from the courts—and that worries me. How much privacy do we really have as Canadians?

While some may argue that journalists should realistically expect some interference from the police, these incidents of surveillance are deeply disturbing. Journalists are supposed to ask the difficult questions and investigate. How are we supposed to perform our duties when those in power are establishing a state of fear and intimidation?

In Edmonton, for example, the police recently admitted to using International Mobile Subscriber Identity (IMSI) catchers, also known as “stingrays,” according to CBC News. These devices allow the police to essentially eavesdrop on any cell phone call within range of the device.

This sort of technology breaches privacy and violates the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the Privacy Act passed, which was adopted in 1983 and serves to protect Canadian citizens from surveillance. It allows the police to easily gain access to the private conversations of any individual, and this is just not right. Where do we draw the line between security and privacy? I can only imagine what the police will be allowing themselves to do next in the name of surveillance, if we continue on this path.

So far, Canada’s two largest police forces—the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP)—are refusing to confirm whether they use these devices, which work by picking up on the cellphone signals of people nearby. Both forces declined to comment when questioned by the Toronto Star with regards to their possible use of “stingrays.” The fact they haven’t denied it leads me to believe they may be using this technology, and it is worrisome.

It is our duty as Canadians and citizens of a democracy to question those with power and always fight for our rights and freedoms.

As Edward Snowden said, “Arguing that you don’t care about the right to privacy because you have nothing to hide is no different than saying you don’t care about free speech because you have nothing to say.”

Graphic by Florence Yee