The recent cloning of monkeys in China highlights potential risks, discoveries and dilemmas

Biologists in Shanghai, China, announced on Jan. 24 their successful attempt at cloning two macaque monkeys, Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua, reported CTV News. Though it was not the first time humans have attempted to clone a non-human primate, Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua are the first to be successfully cloned into “fully developed monkeys,” according to National Geographic.

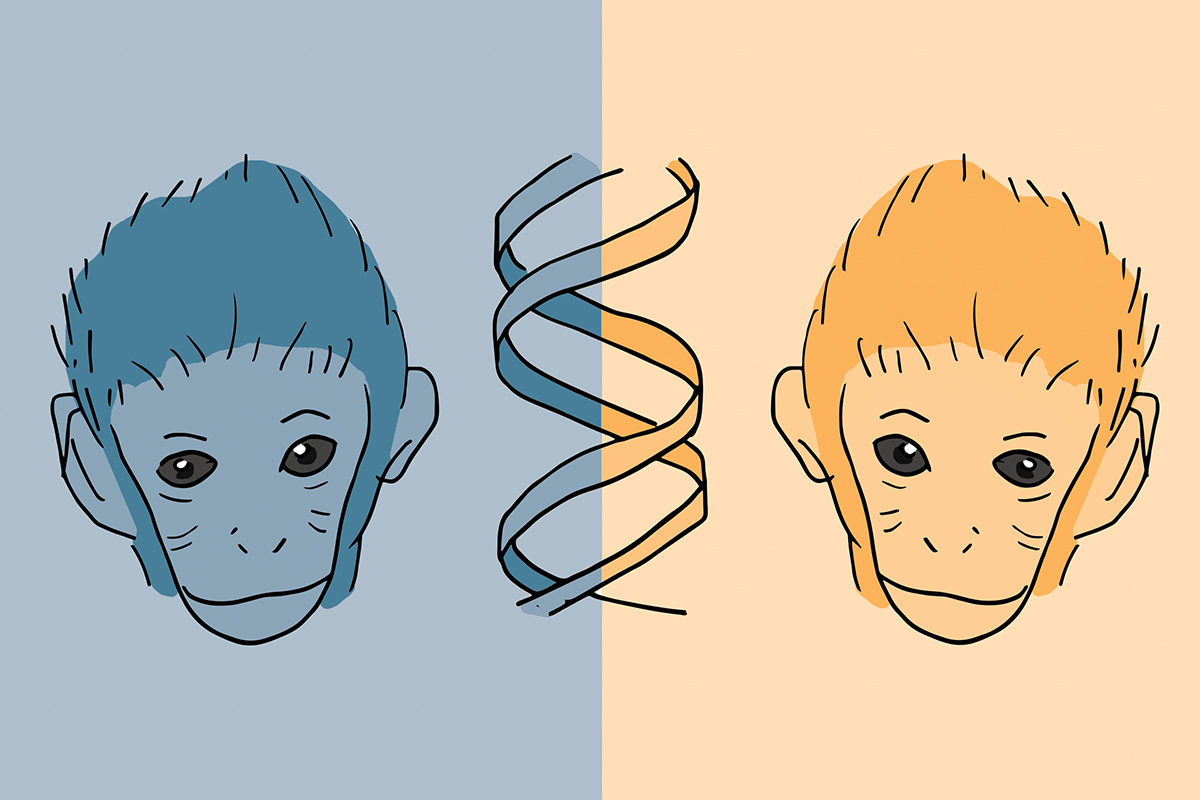

The method used by the scientists was an improved version of the technique used to clone Dolly the sheep in Scotland in 1996. The process is called Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer, and is described by National Geographic as the transfer of the nucleus from the cell of an animal donor into the egg cell of another similar animal, where a simulated fertilization occurs. Once it reaches a certain level of maturity, the egg is then implanted in a surrogate mother. In this case, the subject was a macaque monkey instead of a sheep.

This latest cloning success highlights a breakthrough in both the biological and medical fields. The macaque monkeys were chosen specifically because researchers insist that studying a primate model is essential for researching complex human diseases, according to National Geographic. Due to the genetic similarities between humans and other primates, cloning monkeys can lead to a better understanding of mental and physical conditions like Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease and autism.

However, this breakthrough also raises some ethical questions about the field of cloning and what it could mean for the future. It will surely reignite discussions about the laws and regulations put in place to control the practice of cloning.

Presently, more than 46 countries, excluding the United States, have banned human cloning. In China, while cloning is permitted for research purposes, it is prohibited for the purpose of reproduction, according to National Public Radio (NPR). The team of Chinese researchers responsible for the procedure claim they have no intention or valid reason to begin cloning humans, according to National Geographic. They have said their only purpose is to study how cloning can improve the medical field.

According to an article from The Cornell Daily Sun, there are two possible applications for human cloning. The first involves cloning another human, either living or deceased. The other involves using therapeutic cloning to treat illnesses using stem cells from human embryos.

One of the most prevalent ethical dilemmas surrounding cloning is how it potentially disregards life, rights and dignity. Through therapeutic cloning, an embryo is created for the sole purpose of scientific progress.

Another critical issue is the controversial mistreatment of and experimentation on animals. According to Reuters, the process used to clone Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua has a low rate of success and required 127 eggs to produce two live births. It doesn’t help that China is also facing scrutiny about the safety and ethical treatment of animals, in science and in general, since the country has no laws in place against animal cruelty, according to National Geographic. Fortunately, grassroots animal welfare groups, like the Freedom for Animal Actors (FAA), are helping to strengthen the country’s stance against animal cruelty.

The Chinese research team behind Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua have said they are monitoring the macaques’ long-term health, and that further improvements in genetic research and technology will limit the need to perform experiments on non-human primates, according to National Geographic.

Personally, I think the idea that cloning could potentially cure illnesses is a compelling argument, and is arguably a good thing. Yet, I also believe there is a risk scientists will take this too far. It isn’t hard for humans to lose their sense of ethics and conscience in the quest for scientific progress. At this point, it is crucial for us to retain our ethical standards and avoid potential risks that could harm people and animals. As writer Kristin Houser stated in an article published on Futurism, “scientific advancements aren’t always determined by what we should do, but simply what we can do.”

Graphic by Zeze Le Lin