Brotherhood showcases the struggling humanity of a war-torn family

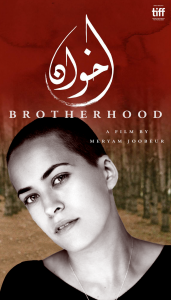

There’s a lot that could be said about Concordia Alumna Meryam Joobeur’s Brotherhood. The short film was nominated for an Oscar in the live-action short-film category. In its simplicity, the film showcases the deep disturbance and shifting family dynamics caused by the emergence of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS).

Centred around a distrusting and hardened father, Mohamed, the 25-minute short follows the story of his moral conflict upon the arrival of his eldest son, Malik, who had left to fight in Syria with ISIS. Malik returned a year later with a very young and pregnant wife, clad in a niqab— forcing the father into a deeper conflict within himself.

There are a couple of things about the North-African and Middle-Eastern cultures that are important to know. Family is a founding value in this culture; a father’s responsibility towards his family is heavy and permanent. This responsibility is emphasized in the dialogue between Mohamed and his wife, Salha, where he says “I have slaved away my life for these boys.”

Salha, the boy’s mother and Mohamed’s wife, is mostly passively present; not so much taking part in the moral conflict that is set throughout the whole story. In a way, it’s reflective of the passive role of mothers in dealing with life-changing decisions. Although her role is not active, her presence certainly is; she welcomes Malik back without a second thought, expressing “as long as he’s alive, I’ll stand by him and defend him.” There’s a word in Arabic that perfectly embodies what a mother represents: hanan. It means tenderness. A mother’s love is never distrusting, always loyal to her children, and never-fading.

Watching this film was like reading a book—there was a lot left for imagination, for your own understanding. Nothing is said explicitly, nothing is forced upon you. There are a myriad of ways to interpret the struggles of Mohamed’s family. The underlying pressures of societal family values combined with this family’s faith and morality are all challenged when Malik left for ISIS. As an Arab, I think of what must have been going through Mohamed’s mind when Malik returned: he is my son, but he brought shame upon us. He is my son, but he joined an immoral killing machine. He is my son, but he impregnated a child.

Mohamed’s inner struggle to accept the moral wrongs of his son is the core of Joobeur’s short. There’s a never-ending battle between unconditional love for his flesh-and-bone and loyalty to his moral grounds, and what he believes his religion, also his son’s, actually stands for.

The film is raw, and not very easy to watch. The very opening scene sees Mohamed and his middle-child, Chaker, looking at a flock of sheep that had been attacked by a wolf—a sheep was bleeding profusely, and the father and son went to kill it. The togetherness of this act strengthens father-and-son narrative, while also highlighting the contrast between the two characters—the father as a hardened man, and the son, sensitive and hesitant to kill. This contrasts directly the idea of Malik killing with ISIS— something Mohamed accused him of in one of the scenes, even though Malik said he never killed anyone.

The soundtrack consisted of wild sounds, setting a rural and haunting environment for viewers, forcing them to listen to the tension that is almost palpable on screen. In a scene where Malik takes his two younger brothers to the beach, a moment of confession ensues: “I regret going to Syria,” Malik told Chaker. “Promise me you will never go.”

It’s reflective of how misconceptions and false propaganda hurts people.

In parallel to Malik’s confession, Mohamed makes a call. An argument between him and Salha leads Malik’s young wife, Reem, to confess that the baby was not his—she was forced to “marry” many fighters. In other words, she was raped by ISIS terrorists and got pregnant, and Malik, while running away, chose to help her even though he knew it would only make things worse with his father. That call was to authorities to take Malik away, a deed Mohamed instantly regretted as he ran towards his sons at the beach, calling for Malik in breathless shouts—only to realize it was too late.

Brotherhood, in asserting the difference between the Tunisian-Muslim family and ISIS, very subtly says that ISIS is not Islam. I’ve read great reviews of the film, but none of them recognized this—most of them related the strain between Mohamed and Malik to the latter leaving family responsibilities, and none highlighted the fact that he left to join a terrorist group, and that was the source of Mohamed’s moral conflict.

ISIS shook the Middle-East and North-Africa. It shook the world of Islam and only fed Islamophobia further, it justified the West’s pre-existent bias and discrimination. Brotherhood depicts how torn families suffered the aftermath of such a phenomenon in the rawest and most simplistic way—strictly humanized, embellished in nature, and thriving in moral conflict.

Brotherhood can be watched online, on vimeo.com.

Collage by Laurence Brisson Dubreuil.