Canada is finally breaking the silence around anti-Asian racism

Ever since I’ve been old enough to recognize patterns of race and gender-based discrimination in society, my mother has denied being a victim of either of those things.

My Taiwanese mother immigrated here over 20 years ago. Single-handedly, after only a few years of living here, she had bought a house and started taking French classes offered by the Quebec government’s immigrant integration services — the fourth language she would be learning after Hokkien, Mandarin, and English.

I’ve witnessed her being talked down to by bureaucrats at government offices and had countless store employees turn to face me to answer a question she had asked, sometimes with a look on their face that was asking me to relate to their deliberate misunderstanding of her Chinese accent. As a teenager, I remember looking at my sister as we drove past someone who had just yelled out a racial slur and commented on our mom’s driving. I’ve never rolled up my window so fast. To this day, I’m still glad she didn’t hear it.

And yet, despite all this, my mom is probably the person I know who is the most optimistic about the social climate of Canada; she’s never let her optimism and gratitude towards the country be clouded by microaggressions and negativity.

I was on exchange in Singapore when COVID first hit, when the western world was busy making coronavirus memes instead of planning ahead for an inevitable pandemic. And one day, on a WhatsApp call with my mom, as I was telling her I was okay and was monitoring my temperature every day, she told me she didn’t want to go out too much because there were increasing reports of anti-Chinese violence in Chinatown. She told me there was a lot of racism around Montreal those days.

To say the least, that made me terrified.

East Asians are often dubbed the “model minority”: they have the benefit of a skin tone fairer than other ethnicities’. Some have even said they don’t fall into the “people of colour” category.

And the stereotypes associated with being East Asian, including academic excellence, obedience, bring really good at martial arts, and eating dogs are frankly not as harmful as being associated with inherent violence, terrorism, and drug addiction.

They also experience discrimination to a lesser degree than other visible minorities; Chinese people in Canada only earn 91 cents for every dollar a white person makes, which is far higher than for, say, Black people, for whom this number is 73 cents.

Yet, the model minority attribution becomes especially toxic when it comes as an excuse to dismiss anti-Asian racism on the belief that Asian people don’t stand up for themselves or fight back. It takes advantage of Asian stereotypes being associated with silence and endurance to double down on bullying, microaggressions, theft, and violence.

In my view, this is why we never heard about anti-Asian hate crimes until the numbers shot up by over 700 per cent in the past year, like the Vancouver Police Department has reported. In Canada alone, community-based groups have reported over 600 cases of racial aggression against Asian people since the start of the spread of COVID-19. In the first four months of 2020, 95 per cent of reported incidents happened in March and April, as the country entered lockdown.

Our generation is pretty good at recognizing and calling out discrimination when we see it, and especially taking a stand against it. But the state of anti-Asian racism in Canada has gotten so bad that even my mother, who has always had so much faith in this country, has noticed and become apprehensive because of it. For a second-generation immigrant, it’s almost worse than seeing your mom cry.

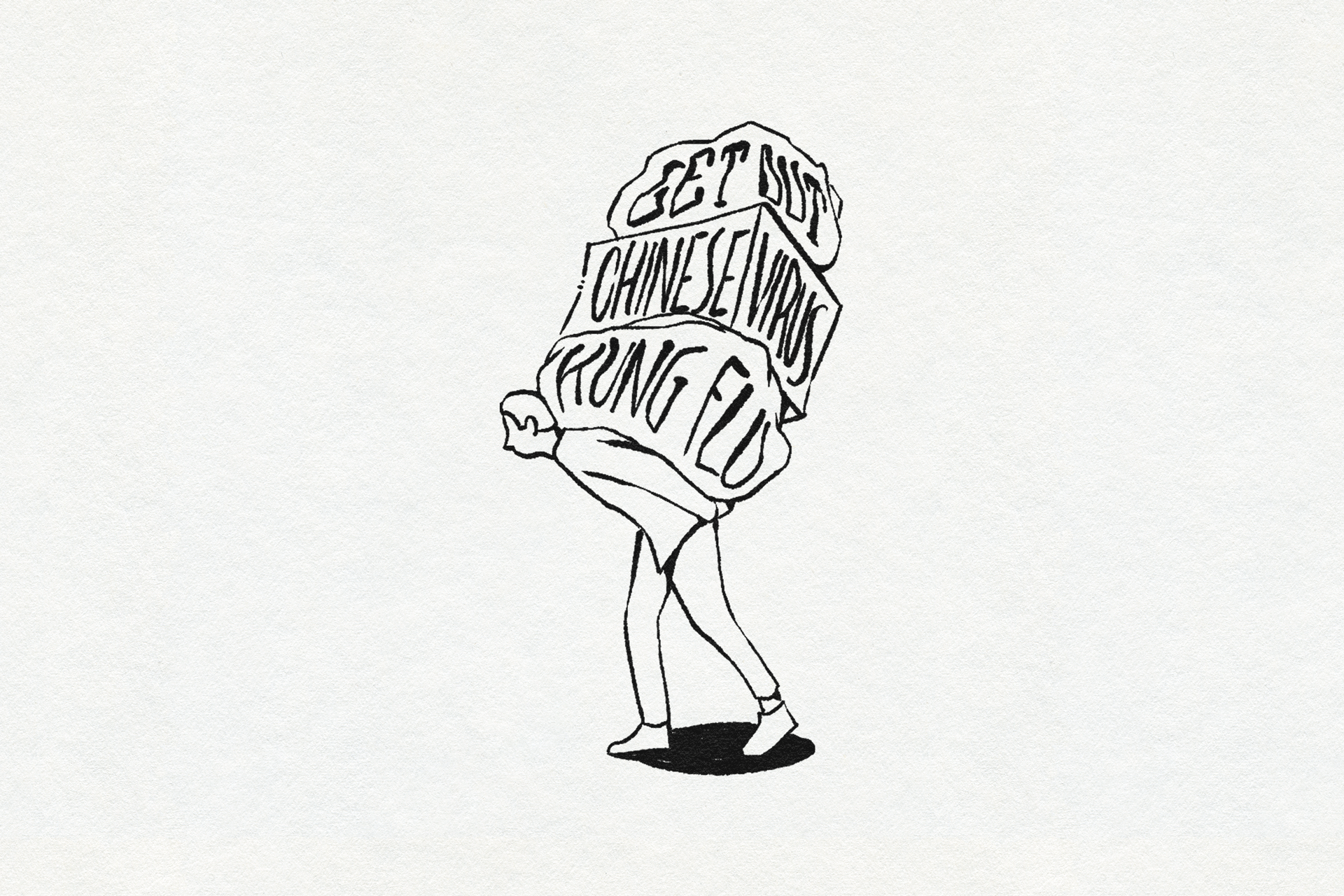

Graphic by Taylor Reddam