If we were to live by the rules of NBC’s The Biggest Loser, one of the most popular reality competition shows on the tube, dropping more than half your weight over the span of a television season is nothing short of an extraordinary success.

And it’s inspiring, really, to see obese people who couldn’t walk up a flight of stairs be able to run a 10K after weeks of grueling exercising and dieting. The contestants’ weights keep dropping and they are rewarded almost immediately by receiving kudos from the show’s personal trainers and admiration and jealousy from their opponents. The contestants’ backgrounds and life stories (and the producers’ sneaky, strategic editing) make viewers feel like there could be a biggest loser in everyone.

Contestants exercise to better their health and their lives; the “biggest loser” also gets a cash prize. At home, viewers are treated to fat people’s families’ ecstatic faces at the contestants’ new svelte physiques.

“Look at how happy they are,” they must think. “If I get skinny, people will like me more, too.”

Victor Avon used to be obese. Today, he is closing in on his tenth year battling an eating disorder. At his heaviest, Avon was a 19-year-old college freshman tipping the scale at almost 300 pounds. After teenage years in high school that seemed like they would never end, he whispered to himself words that would change his life forever.

“It was March 4, 2002,” Avon remembers. “I was in my student dining hall and I remember I was standing in line at the grill and I said, ‘F it, I’m going to go on a diet.’ By making that decision, I pushed that first domino over. I didn’t know what I was doing.”

He continued, “I hated my body growing up because of how people made me feel and how I was treated, and because I couldn’t change myself. I couldn’t take control of my body and get that perfect body that everybody would love me with. I had a lot of self-hate. I created the eating disorder as a way to control what the world could see. I was going to get the body that everyone always made fun of me for not having. I’m going to be the person they always wanted me to be, and I’m going to be happy.”

Psychologist Anna Barrafato runs a support group for students with eating disorders at Concordia University’s Counselling and Development Centre. She says eating disorders can be triggered by many things, including a childhood trauma or a lifelong battle with one’s own body image. They can also happen when dieting turns into an obsessive fear about getting “fat” and an addiction to losing weight. She says eating disorders are sometimes developed as a coping method.

Avon describes his father and uncles as ultra-masculine, and when he wasn’t bullied by his schoolmates, his family constantly made him feel like he wasn’t good enough. He had no one to turn to, and he says his eating disorder turned into his best friend. It was also the only thing in his life he had complete control over.

Barrafato says that eating disorders undoubtedly transcend gender, race, culture and socioeconomic status. She says the belief that an eating disorder is a woman’s affliction dissuades men into seeking appropriate help when they are showing symptoms. Studies also show that people believe men obsessed with their appearance and weight are gay. The fear of being mistaken for a homosexual or thought of as unmanly is strong enough for some men with eating disorders to never admit they have a problem.

Avon’s dieting in 2002 spiraled out of control into anorexia nervosa, which he was not diagnosed with until 2006. When he finally sought help and checked into Princeton University Medical Center’s eating disorder unit, he weighed 130 pounds. “They were surprised I was still alive,” he remembers. “My body was shutting down. My fingers were blue. I weighed less than my mother.”

Avon’s body mass index went from 40.7 to 17.6. A person’s BMI is calculated by dividing the person’s weight in kilograms by the square of the person’s height in metres. By North American standards, a person with a BMI over 30 is obese, while a BMI under 18.5 is considered underweight. According to 2004 figures from Statistics Canada, more than 23 per cent of Canadian adults and 30 per cent of American adults were obese.

According to the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders used by mental health professionals in North America, anorexia nervosa is diagnosed overwhelmingly in females, with up to 90 per cent of cases seen in women. The National Eating Disorders Association, for which Avon is the male spokesperson, echoes that statistic: of the more than 10 million people struck by eating disorders in the United States, only 10 per cent—or one million—are men.

“I stuck with the old stigma that men can’t get eating disorders,” Avon recalls. “I didn’t think anything was wrong with me. It was easy to fool myself for a long time because of the gender issue. I had never in my life heard of a guy getting an eating disorder. I also had a lot of positive reinforcement, ‘You look great, you’re taking care of yourself, dropping some weight and getting healthy.’ I just thought that it was the lifestyle that I had chosen.”

Avon has written a book about his experience, My Monster Within: My Story, in which he describes the mental anguish he felt when he missed a workout. “If I decided to run 55 minutes one day, instead of 75, the backlash that came with that in my head―it was not normal. It was never an option not to exercise. It was never an option to change without severe mental anguish. It was a total belief that if I changed one thing I did for one day, that I’d wake up the next day having gained 100 pounds overnight. It was fear that people would start rejecting me again. It was the fear that everything I ever felt growing up would come flooding back and happen again.”

From 2002 to 2008, Avon severely restricted his daily food and calorie intake and exercised like a “madman, to the point that I have major joint problems today. The only things I ate for six years were: chicken breast, turkey breast, beef, broccoli and some cheese. That’s it.

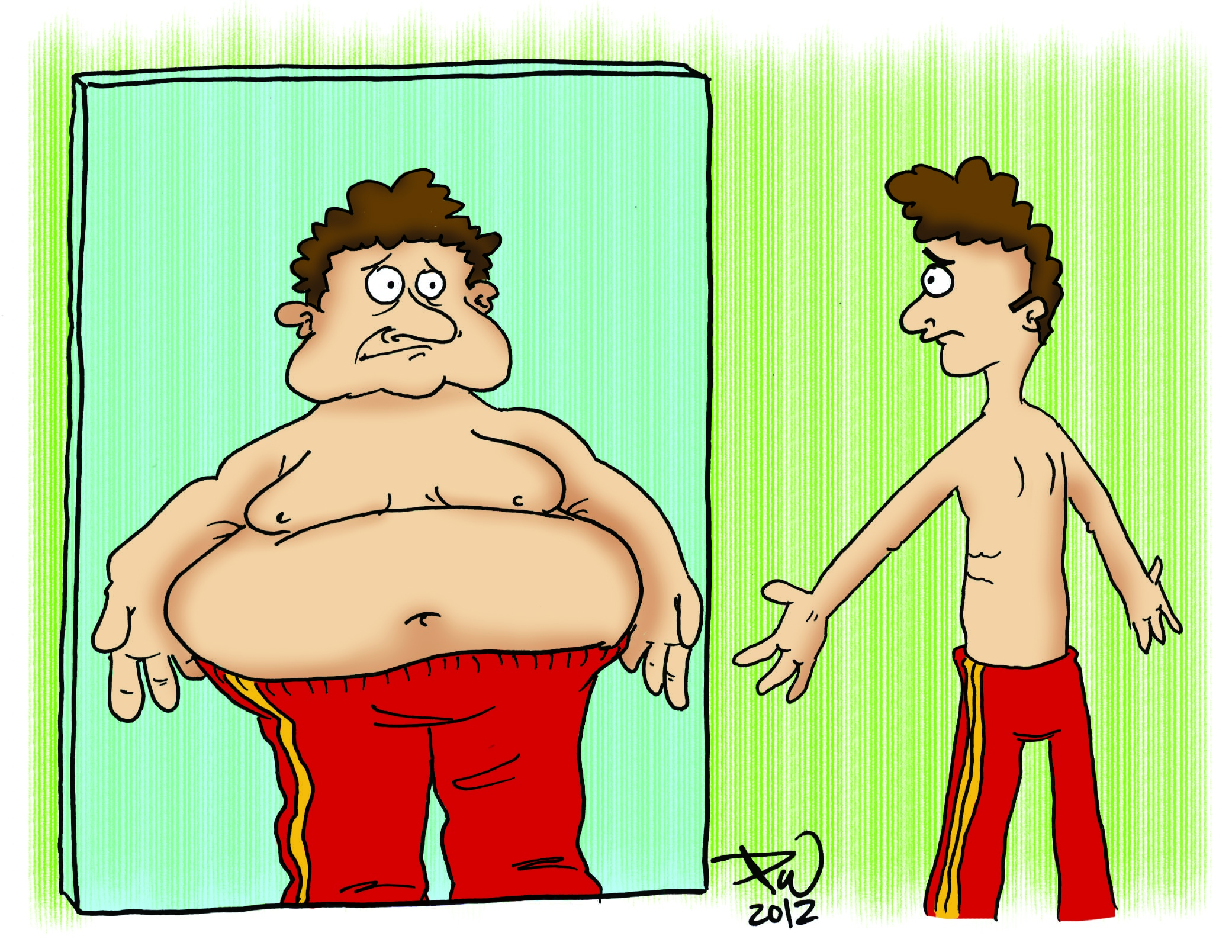

“I got myself to the weight that I thought I would be happy with. My physical body changed, but everything up here,” Avon said, pointing to his head, “always stayed the exact same. I still felt like I was in my old body, so I had all the insecurities that I lived with. It never got easier. I was never happy.”

Avon was hospitalized for four months, where he met with therapists and psychiatrists daily. Patients were also required to attend group therapy sessions where they essentially had to be retaught how to eat again and why food is so important for the human body. Avon, now 29, considers himself on the road to recovery, a road he has been trekking since 2008. “I was so sick for so long; six years with the eating disorder, and for most of my life I had major body image and food issues. I don’t want to say that my wiring’s all messed up. It’s a goal of mine to be fully recovered, but I don’t know if it’s going to happen.”

Avon says he has been on the road to recovery since 2008. As a spokesperson for NEDA, he attended a conference on eating disorders in Los Angeles over the summer hosted by medical professionals in the field. While Avon’s goal is to raise awareness for men afflicted by eating disorders, he found it disenchanting when psychiatrists turned to his accompanying wife to ask her how long she was sick for, requiring Avon to interject.

According to Barrafato, eating disorders are lifelong struggles and “it takes a very strong will to say that you are okay with the way you look.”

“I don’t think I’m happy with the way I look,” admits Avon, “but I accept the body I have. I could stand in the mirror and pick myself apart if I wanted to, but doing that only fuels the illness. I know I will never have the perfect body that I once craved, so the way to live and be okay with myself is to accept the body I am given and do my best to keep it healthy, to not focus on the outside but rather the inside.”