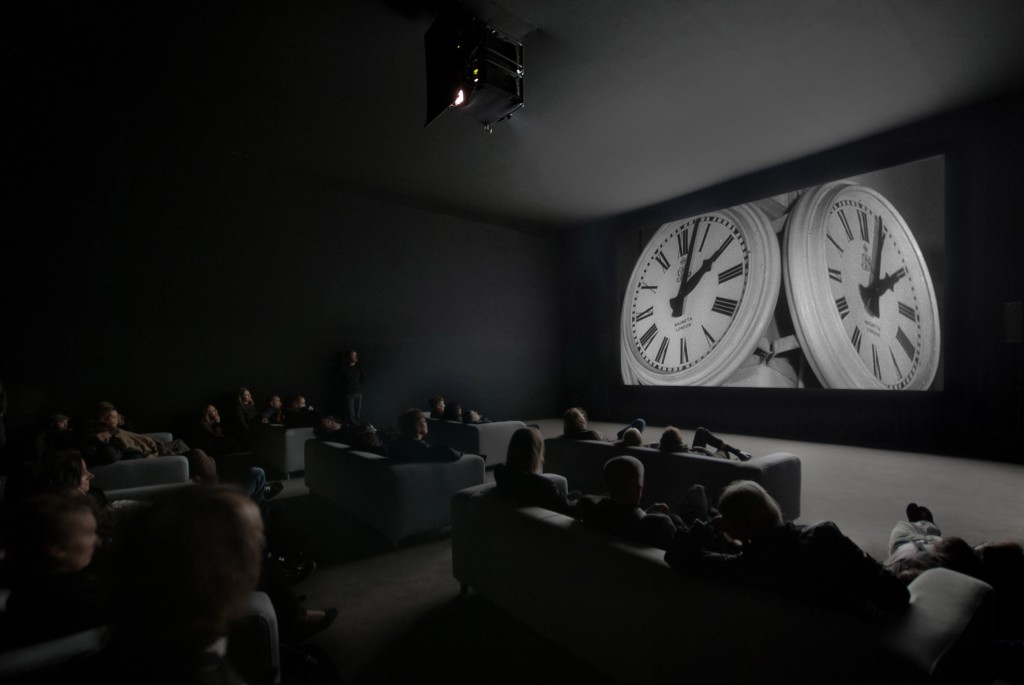

The Clock is a 24-hour video installation that traces through the history of world cinema and television

Time. It is unavoidable, reflective, and theoretical. It is also much, much more.

As such, Christian Marclay’s exhibition, The Clock, highlights the myriad characteristics of time and the way it affects

humans on a grand scale. Winner of the Golden Lion, the top prize awarded at the Venice Biennale, this exhibition is sure to make you look at your watch in a completely new way.

The Clock is a series of vignettes taken from films and television shows showcasing cinematic scenes where characters are shaped or altered by the concept of time. It took Marclay and his assistants over three years to produce this 24-hour-long cinematic chef d’œuvre which pulls the audience into the narrative fold with gratifying results. You are forced to ponder, theorize, deliberate and conclude. And start again.

The Clock works in a number of ways. First of all, it demonstrates the narrative quality of time. As the clips reveal, the time pinpointed in various clips marks the actual passing of time. So, for example, if it is currently 11:20 a.m. and you are watching the clips, the scenes will showcase films where the time is 11:20 a.m, and so on.

Audience members are invited to be actually part of the filmic narratives, whereby the passing of time is revealed. It’s genius, at best. As Zadie Smith from the New York Review of Books said, The Clock is “neither bad nor good, but sublime.”

The audience is subjected to a wide variety of scenes, and to a variety of emotions at that. Marclay shows how time can be theorized. We see a small boy earnestly drawing a watch on his wrist with a felt pen, then bringing his wrist to his ear and hearing ticking sounds.

Time is a memory-shaper. We see a woman standing over her dog. She has just realized that the dog had passed away. She glances at the clock on the kitchen wall, and the audience understands — she will never forget the exact hour at which her dog died.

Time also acts as an event-maker. We see a couple glancing outside and worriedly eyeing at their watches. “It should have happened by now,” mutters the man, referring to a bomb detonating.

Time can seal someone’s fate. A blonde woman sits nervously smoking in a hall, checking the big clock on the wall. A uniformed guard approaches her and declares: “You can come in now. The jury has decided.”

Alternatively, we see an even darker side to the power of time. A man is holding a gun to a woman’s head, singing: “Ain’t got no alternative, ya got 40 seconds to live.”

Time is also, sadly for some of us, unavoidable — hello, Monday mornings. The audience giggles when a man is brutally woken up by his alarm clock, emanating “Jingle Bells” music. The man promptly throws the alarm clock against the wall and repeatedly sends empty beer bottles its way, screaming: “Fuck you!”

Finally, time can accentuate our boredom. In one clip, we see actor Matt Damon walk into a room and suppress a sigh, as if once again being confronted by a state of utter monotony.

The clips are as diverse as can be, showcasing beautiful black and white shots of women with pearl necklaces, followed by clips of American men zooming off into the desert. All of the filmic genres are covered: romance, action, thriller, comedy, gangster, musicals, adventure, historical. You name it, and it’s there.

The Clock speaks to us on many issues, but it fundamentally succeeds in bringing people to a more complex and thorough appreciation of those little ticking machines we wear on our wrists. Time exists, and merits our attention. Although it is conceptual, time delivers a powerful message: it is here, and it is here to stay.

The Clock exhibit runs until April 20 at the Montreal Museum of Contemporary Art.