The seriousness and jest in satire and religious mockery

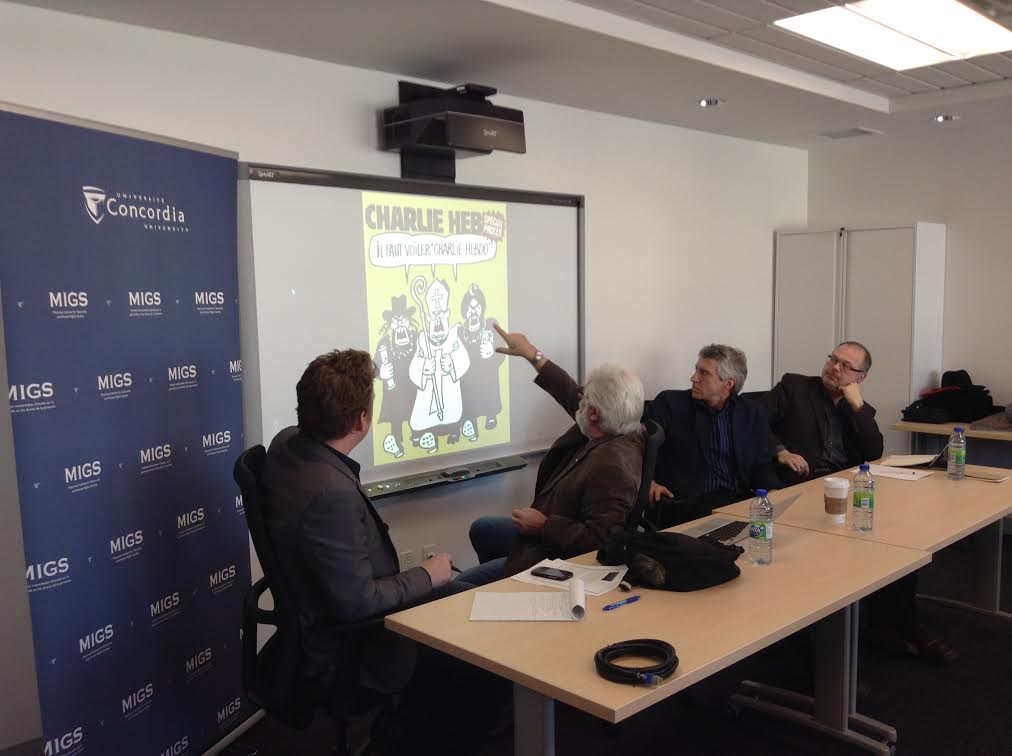

Two satirists and a religious studies professor walk into a room: this isn’t a joke, but what happened last Tuesday at an event sponsored by Concordia’s Montreal Institute of Genocide and Human Rights Studies (MIGS) in light of the Charlie Hebdo attacks in France.

The panel’s resident academic and assistant professor in the Departments of Religion and Theology, Dr. André Gagné, began by contextualizing the discussion and showing the historical and modern differences in Islam itself. Islam, said Gagné, has had a long history of using imagery, and rather than forbidding its making, made the distinction between imagery for representational and illustrative purposes—which was sanctioned— and imagery as something to stand between God and man and be the object of worship—which was considered idolatry.

“It is sad to see there is actually little justification for such horrific crimes,” he said, continuing: “[these are] interpretations over which people are fighting to the death in the Middle East.”

For Gagné, religious adherents pick what they will of their religions, and thus picking one ‘authentic’ Islam among many for the role of yardstick is an ambiguous concept: “There is no such thing as a true or false Islam. Scholarship has abandoned the concepts of orthodoxy and heresy. What we see are simply the various manifestations or facets of a religion,” he said.

However, this does not mean that the violence exhibited by some Islamists is completely groundless, especially when one considers the concept of abrogation, whereby latter, generally more forceful and violent, verses of the Qur’an (revealed at a time where ascendant Islam feared less from its pagan milieu) replaced older, sometimes more peaceful commandments revealed when Muhammad needed to tread more lightly.

“People who say that the Bible or the Qur’an do not contain violent commands or narratives have not carefully read them or are simply deluding themselves. Holy books do contain the good and the bad,” he cautioned.

These exhortations can sometimes give direction when personal and collective injustice is experienced, or when people searching for an aggressive worldview as answer to the ‘hopelessness they experience.’ When one is vulnerable, says Gagné, is when one is most open to radicalization, and it is up to modern secular societies to both integrate and accept religious traditions and to maintain a critical perspective toward ideologies by upholding humanistic principles.

“Ideas that promote violence should be denounced and resisted. This is why Islam, or any other religious tradition that stifles human dignity, should be critiqued.” For Gagné religion, unlike other parts of culture, is still strangely off-limits and sacrosanct. Pluralism entails the right to disagree, and the need for religions to cope with disagreement—something contemporary global Islam may be as yet unable to do.

“Muslims can surely disagree with the assessment people can have of their tradition, but the best way to state their case is with ink and paper. This is what freedom of speech is all about,” he said in a brief statement at the start of the panel.

“It is strange how we are quick to say the perpetrators of the Paris attacks do not represent true Islam, but rarely say the same thing when the attacks are far from home,” said Gagné, referring to the West’s obsession with Islamist attacks only insomuch as it was the centre of the story. Ignored is the the rampant Muslim-on-Muslim violence the world over.

Montreal Gazette cartoonists Pascal Élie (Pascal) and Terry Mosher (Aislin) balanced the intellectualism with the welcome dose of (solemn) lightheartedness that befit satirists.

“If you’re going to laugh at other people, you’re going to have to laugh at yourself. The proof is in the pudding,” said the irreverent and rascally Mosher. “When the Pope says we are not allowed to poke fun [at religion],” he continued, referring to the Pope Francis’ reaction to the attack when he said the world should not be surprised by violence when the sacred is mocked, “let me be blunt: fuck him. This is a very established part of the process. We poke fun, this is what we do, and we’re a very important part of freedom.”

Fittingly, humorous self-criticism alongside Gagné’s academic introspection was at the heart of the message Pascal and Aislin delivered. More than anything they pointed to the need for criticizing ourselves and making fun of our own actions, as during the PR nirvana that occurred when world leaders joined in a solidarity march in Paris in support of the freedom of expression. The amusing thing the two noticed—and drew—was a good portion of those ministers and presidents were part of coercive, oppressive regimes that have a long pedigree of media control and intimidation.

“We grab these things and sort of run with them,” said Aislin, cycling through a series of cartoons poking fun at the ‘Je Suis Charlie’ trend. “You have to get cheeky and poke fun.”