Dawson’s Daughters of the Revolution is a complex, political play

Theatre reviews should be easy to read, easy to process, and not riddled with complex terminology and jargon. That said, it is very difficult to write a comprehensive, all-inclusive review of a production that was written in the almost impenetrable language of “revolution.”

Let me preface this review by saying that the professional theatre students of Dawson College faced a multitude of obstacles in their staging of David Edgar’s politically-charged opus Daughters of the Revolution, and managed to proceed with relative success.

The play, written by Edgar in 2003 as the second of a two play series about American politics, follows community college professor and former ‘60s activist Michael Bern (played by Jean-Michel Chartier). During a surprise birthday party thrown by his girlfriend Abby (Keren Roberts), he is presented with a copy of his FBI file, discovering that one member of a group of activists he was involved with was, at the same time, an FBI informant.

Following this alarming realization, Bern sets out to track down the seven other members of his former anti-government group and uncover the traitor. The journey takes him from the ghetto to the throes of a political campaign, a gated community, and the depths of a sacred redwood forest.

The play is easy enough to synopsize on paper, but is entirely a different beast when executed in front of a live audience. Each scene was weighed down by long-winded, disjointed speeches and antiquated turn-of-phrase that was very difficult to understand. Without a prior understanding of the 1960s political landscape, or the overall “speak” of that era’s anarchists and revolutionaries, the average audience member would be lost.

Even our protagonist seemed confused, and at some points bored, in the tedious delivery of his lines. The two most striking performances belonged to secondary characters. Jack Sand (Nils Svennsson-Carell) appears only for a handful of lines in flashback segments, yet Svennsson-Carell remarkably portrays a renegade, anti-authoritarian hippie with an understated finesse. His dirty, drawly, Matthew McConaughey-esque Southern accent was razor-sharp and completely convincing. Nicky Fournier was also commendable in her turn as crooked, phony politician Rebecca McKeene, a former activist who renounces her views in hopes of pulling ahead in her campaign run.

Though the vocabulary aspect certainly muddled the experience, the rest of the undertaking was admirable. The use of popular ‘60s songs to transition between scenes kept the audience in good spirits, and the set design, while minimal, facilitated the many changes needed to follow the plot’s trajectory.

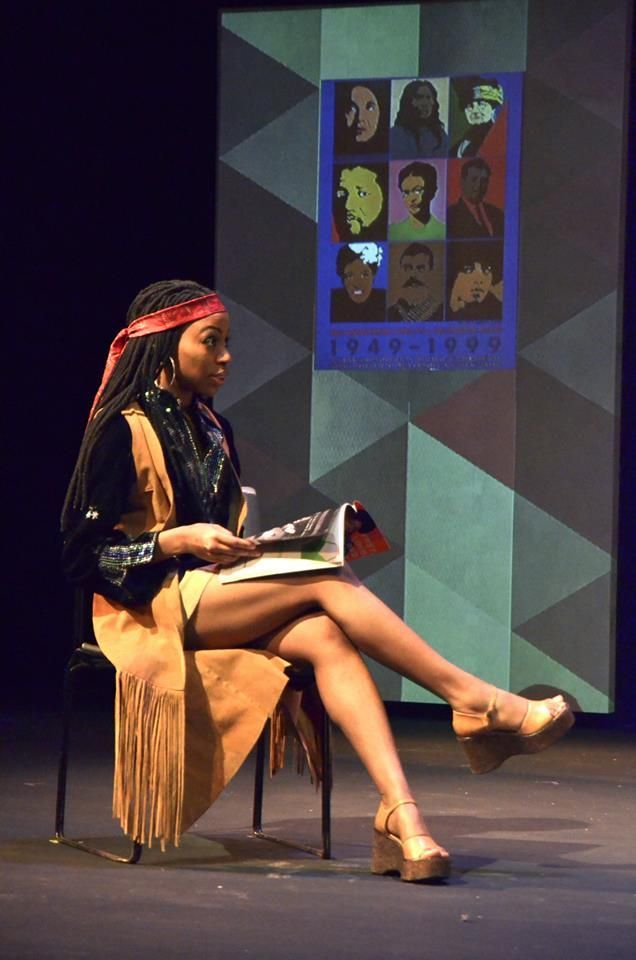

The costuming was also one of the more memorable aspects of the production, and was no doubt difficult to bring about. Not only was there a need for semi-authentic hippie costumes, but costume and makeup designer Pierre Lafontaine had to convincingly age quite a few members of the young cast. These two aspects combined actually produced a roster of believably middle-aged characters.

Overall, Director Doug Buchanan managed to put forth a production whose value extends far beyond the reach of a typical college student. A few technical glitches and acting unease did not slow the show’s pace. However, audiences are still left with one fundamental and still unanswered question in mind, which does impact the overall comprehension: who exactly ARE the “daughters of the revolution?”