Talk at McGill looks at causes and current issues surrounding the crisis

The Syrian Students’ Associations (SSA) of McGill and Concordia hosted a panel discussion on the Syrian refugee crisis at McGill University Leacock building on Friday. The talk, also co-hosted by Standpoints, Amnesty International (AI) McGill and Concordia, and Journalists for Human Rights McGill (JHR), covered the origins of the crisis, but also the current and future problems the region and the refugees will face.

The conference was comprised of three parts; a video presentation, a talk by the executive director of Action Réfugiés Montréal (ARM) and a panel discussion.

The video presentation included a documentary from The Guardian, “We walk together: a Syrian family’s journey to the heart of Europe” which followed thousands of refugees who decided to walk to Western Europe from Budapest.

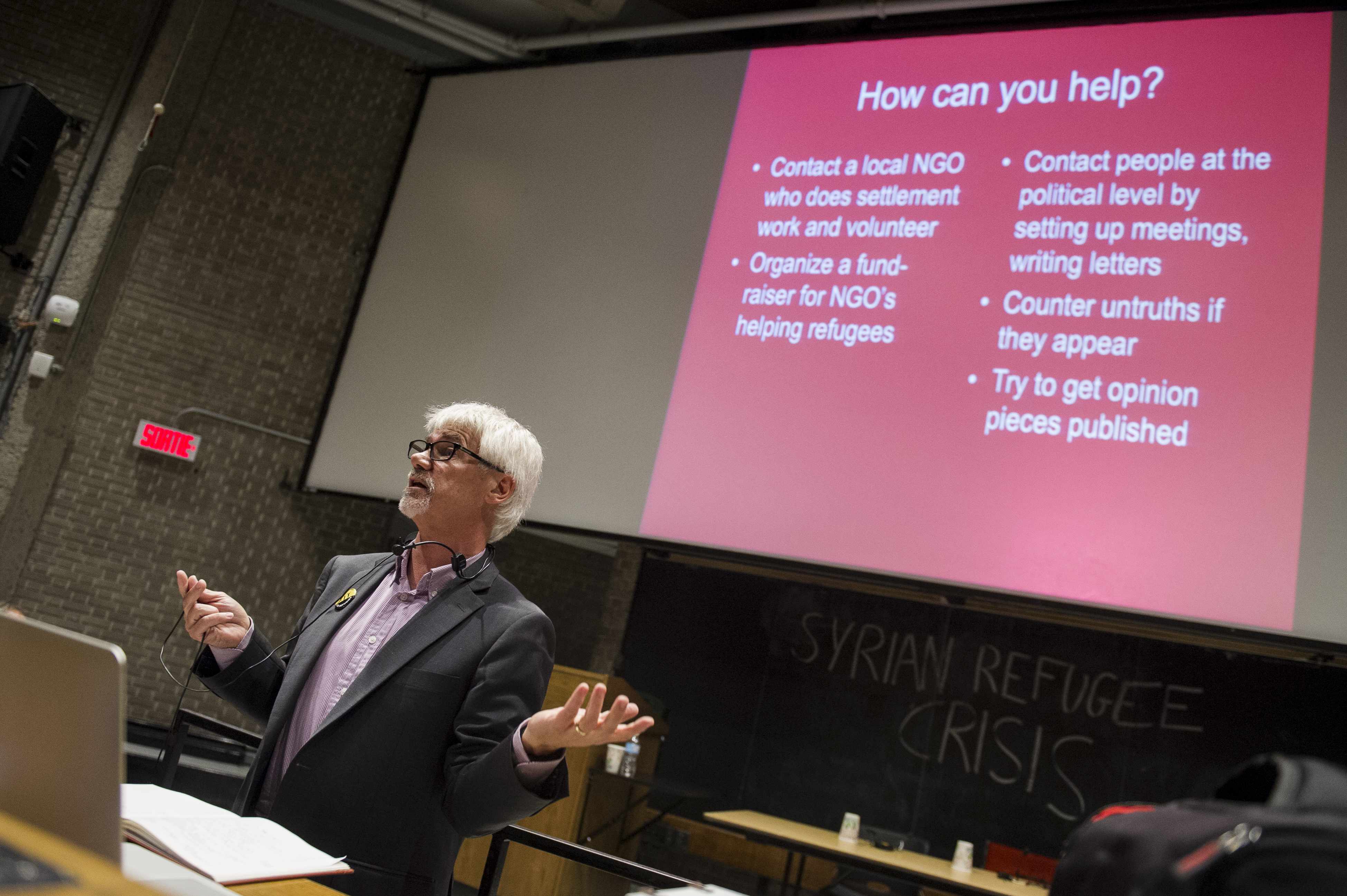

Then, ARM executive director Paul Clarke spoke about his organization’s work to bring refugees to Canada. Clarke opened his talk with the importance of correctly identifying the differences between migrants and refugees.

“Migrants are people who choose to leave where they are because they want to go,” he said. “A refugee is someone who has [undergone] forced migration.”

Clarke also discussed how about 600 refugees in 2015 brought into Quebec were privately sponsored. However, there were only eight government-assisted refugees during that time.

The evening ended off with a four-person panel discussion; Jon Waind, PhD student in McGill University’s religious studies department; Afra Jalabi, a founding member of the Syrian National Council; Matvey Lomonosov, an expert on nationalism and ethnic conflict in the Balkans; and Ecem Oskay, a masters student in McGill’s political science department.

Waind said issues of xenophobia or anti-immigrant sentiment in Europe stems from a “failure of collective memory.” He also discussed how the viral image of Alan Kurdi gained attention internationally through “common human vulnerability.”

“There’s this core feature that we have has human beings,” said Waind. “I don’t just mean our susceptibility of being harmed … it also means a sense of helplessness.”

Oskay, meanwhile, discussed how the European Union set up rules such as the Dublin Regulation and Schengen Agreement which have made it harder for the continent to deal with the influx of refugees. The Dublin Regulation, which was initially established in 1990s, was an attempt by EU member states to coordinate their policies on how they deal with refugees that enter Europe. The Schengen Agreement created Europe’s borderless Schengen area which pushed responsibility of border patrol to the countries along the edges of the EU.

“These two frameworks, the reality that they created is an uneven distribution of responsibilities,” she said. “What we see today, most refugees who come in come through the Mediterranean, so it’s Italy, Spain and also Greece that carry the largest burden of registering them and figuring out what to do with them.” Oskay said inner countries of the EU have been able to avoid responsibility in dealing with the Syrian refugee crisis and straining resources in exterior countries.