Missing Justice organized a discussion on the issue of missing and murdered indigenous women in Canada

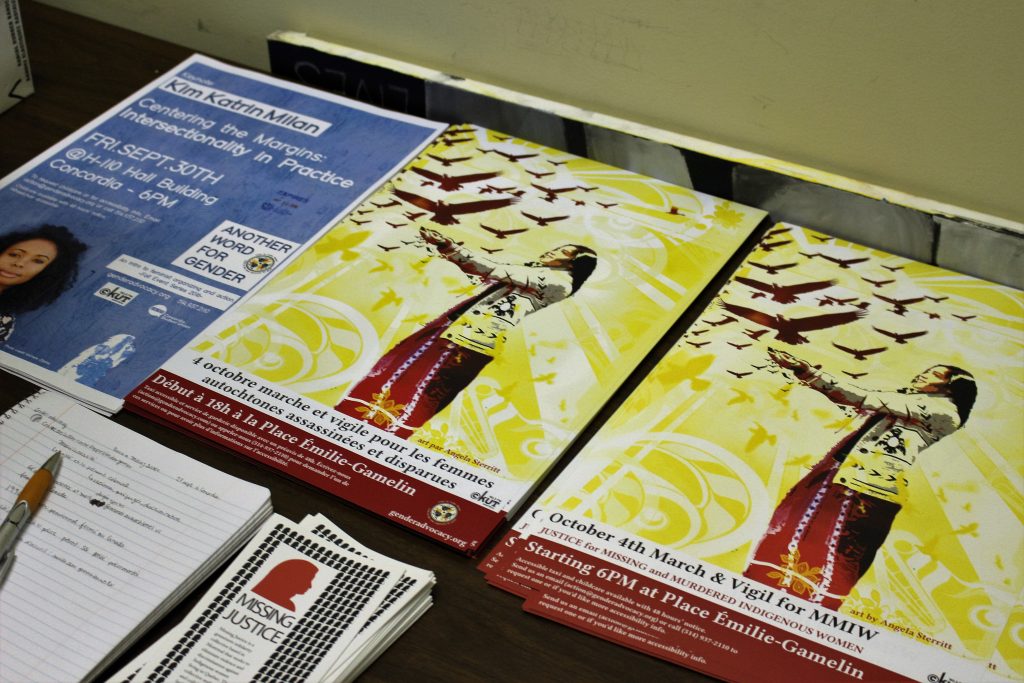

Missing Justice hosted a teach-in on Sept. 27 to shed light and engage Montrealers on the issue of missing and murdered indigenous women in Canada.

The event, facilitated by Missing Justice members Chantel Henderson and Chelsea Obodoechina, explored the past as a cause, the present as a time for action, and the future as hope for the conversation of the issues surrounding indigenous peoples.

A diverse crowd of students and community members, both indigenous and non-indigenous, gathered at Concordia’s Centre for Gender Advocacy for the evening discussion.

Missing Justice is a fee-levy organization that operates under the Centre for Gender Advocacy’s umbrella. According to the organization’s website, Missing Justice’s mandate is “to promote community awareness and political action through popular education, direct action, and coalition-building, all of these in consultation with and in support of First Nations families, activists, communities and organizations.”

Henderson has been a member of Missing Justice since January 2015. She got involved with the organization when she moved to Montreal from Winnipeg for school, two years ago. As a Master’s student in community economic development at Concordia, Henderson explained she had to find an organization to get involved with as part of her program. Henderson knew she wanted to get involved with a centre or organization that focused on missing and murdered indigenous women.

As an indigenous person herself, Henderson wanted to join Missing Justice because she said she feels personally impacted by the issue.

“I went missing when I was 16. I went missing when I was 20. And yeah, I’m here to tell you my story, to tell you why this issue is important,” she said. “Being from Winnipeg, it’s hard to be native and to not know somebody who has gone missing or who has been murdered,” said Henderson.

Obodoechina joined Missing Justice four months ago. “I kept hearing about missing and murdered indigenous women, and I just wanted to get involved any way I could, as a non-Indigenous person,” said Obodoechina.

According to the Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC), aboriginal women are almost three times more likely to be killed by a stranger than non-aboriginal women are. Additionally, the NWAC found that between 2000 and 2008, aboriginal women represented approximately 10 per cent of all female homicides in Canada, even though they only make up three per cent of Canada’s female population.

Last year’s scandal surrounding allegations of sexual and physical abuse of indigenous women by Sûreté Québec officers in Val d’Or caused an uproar in the province, and sparked pressure on the federal government to launch an independent investigation into the issue of missing and murdered indigenous women. The Canadian government announced the launch of an independent national inquiry into the affair on December 8, 2015, according to the CBC.

The facilitators discussed indigenous peoples’ history in Canada, going back to colonization, the Indian Act and the more recent residential school system.

“It all comes back to that. Colonization. The loss of land. The patriarch. And of course, the Indian Act, where indigenous women lost their status. [The women] married non-indigenous men, and therefore that affected generations of indigenous peoples that were, you know, not Indian anymore,” said Henderson. “So it was a slow genocide, and it continues to this day.”

Until Bill C-31, or the Bill to Amend the Indian Act, revised the laws on Indian status under the Indian Act in 1985, indigenous women who married to non-indigenous men would lose their Indian status. Additionally, according to Indigenous Foundations, under Section 12(1)(a)(iv) of the Indian Act, an indigenous child would lose status if both their mother and grandmother acquired status from their husbands.

Henderson and Obodoechina also discussed the negative impacts the residential school system had on indigenous children, mothers and fathers, and generations that followed. They also discussed the lack of representation and misrepresentation of indigenous peoples in mainstream media and Hollywood.

Jonel Beauvais, an attendee of the event, introduced an activity after the first half of the talk. Beauvais is a community outreach worker from Seven Dancer’s Coalition—an indigenous coalition of workers from Haudenosaunee and other areas of the state of New York that seek to educate and support indigenous communities. She had attendees stand in the middle of the room and form a circle that would represent an indigenous community. The “children” sat in the middle, the “mothers” placed themselves behind, and the “fathers” behind them—each row supporting the other with a hand placed on someone’s shoulder.

Beauvais wanted to show that when a member of that community is not there, the community is not complete—the link is broken. “Now you have missing mothers, missing women, missing grandmothers, missing men. If we took at least one person from each level, our circle, our community, is very much deprived now. That’s the kind of state in which we’re in,” said Beauvais, her tone strong, but her voice shaky.