Politics, water and the Experimental Lakes Area take centre stage at the Centaur Theatre

Have you ever heard of the Experimental Lakes Area(ELA) near Kenora, Ontario? Have you ever thought about how much clean water is worth? Are you willing to find the answers by driving across the country in a Winnebago crammed with three children, a husband and a bacon-loving dog? Maybe not, but thanks to Montreal playwright Annabel Soutar, you can experience that journey from the comfort of the Centaur Theatre.

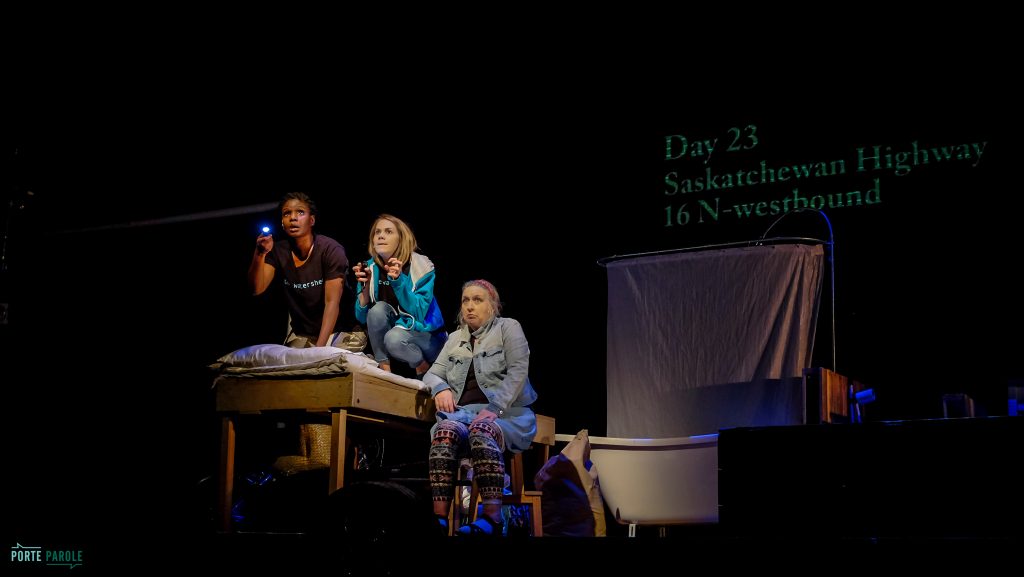

The Watershed is Porte Parole and Crow Theatre’s newest venture in documentary and political theatre. According to the Porte Parole website, documentary theatre is a creative process whereby artists record current event stories from many different perspectives, such as TV segments, in person interviews, radio and online sources. They then sort and mediate those perspectives for an audience in the form of a play. All of the dialogue in The Watershed came from recorded interviews and family conversations about water and the ELA. The Watershed explores Soutar’s journey to find answers about why the Canadian ELA the world’s only freshwater research site, was shut down by the Harper government in 2013, after a scientist who worked there published an unflattering review of the Oil Sands.

Commissioned for the 2015 Panamania Festival, the play begins with Soutar speaking to a local plumber about how water comes into the home. It then grows to become a cross-country journey to find out why the Harper government cut funding to the ELA, which had an annual budget of about $2 million.

The greatest part about this play is its documentary style, specifically the dialogue and characters. The play’s characters range from Soutar’s hilarious children to former Prime Minister Harper and scientist Diane Orihel, who put aside her research to fight for the ELA. The documentary style gives the characters depth, reliability and reasoning since they are real people speaking their own words, rather than ones made up by a playwright to go along with a story.

Soutar’s children, Ella and Beatrice (the third child on the trip, Hazel, is director Chris Abraham’s daughter), played by Amelia Sargisson, and Ngozi Paul, are almost like average audience members within the play. They begin the journey with little knowledge about water, watersheds or where freshwater comes from. As the play continues, the girls become more and more knowledgeable as they sit in on many of the interviews—which the audience also witnesses as they are reenacted on stage.

By the end of the play, the children are conducting their own interviews and learning more about how different people view the oil sands—for example, as a vice president of sustainability for a Montreal oil company said in her interview with Soutar, “People who are for it call it the oil sands. People who hate it call it the tar sands.”

Both The Watershed and Soutar’s previous documentary play, Seeds, have definitely solidified documentary theatre as my favourite style of theatre. While traditional playwriting definitely has its place, this new documentary style feels much more sincere and appeals to modern-day audiences. The Watershed runs until Dec. 4 at the Centaur Theatre. Tickets are available online, at centaurtheatre.com.