Part-time faculty member Philip Szporer breaks down contemporary dance

After a few years of performing with a dance company, Philip Szporer realized he did not want to dance—instead, he wanted to talk about what was going on in the world of contemporary dance.

Over 35 years later, Szporer, now a part-time faculty member at Concordia, hasn’t run out of topics to feed his passion for dance. He hasn’t even run out of inspiration—he’s excited about his upcoming project—a film collaboration, which took him to India during Concordia’s reading week. The film, with Shantala Shivalingappa, who performs the southern Indian classical dance style of kuchipudi, has been in the works for three years. The 10-minute dance film will capture Shivalingappa as she dances in this classical form. Szporer beamed when he said the project will be filmed in Hampi, India, a cherished place for Shivalingappa and a new location for him.

“It’s going to be fascinating. [Shivalingappa]’s a marvelous artist,” Szporer said. One of the first times Szporer worked with her was when he was a scholar in-residence at the Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival in the U.S. After getting to know her form of dance and witnessing a part of her production, Szporer said to himself: “That could be an amazing film.”

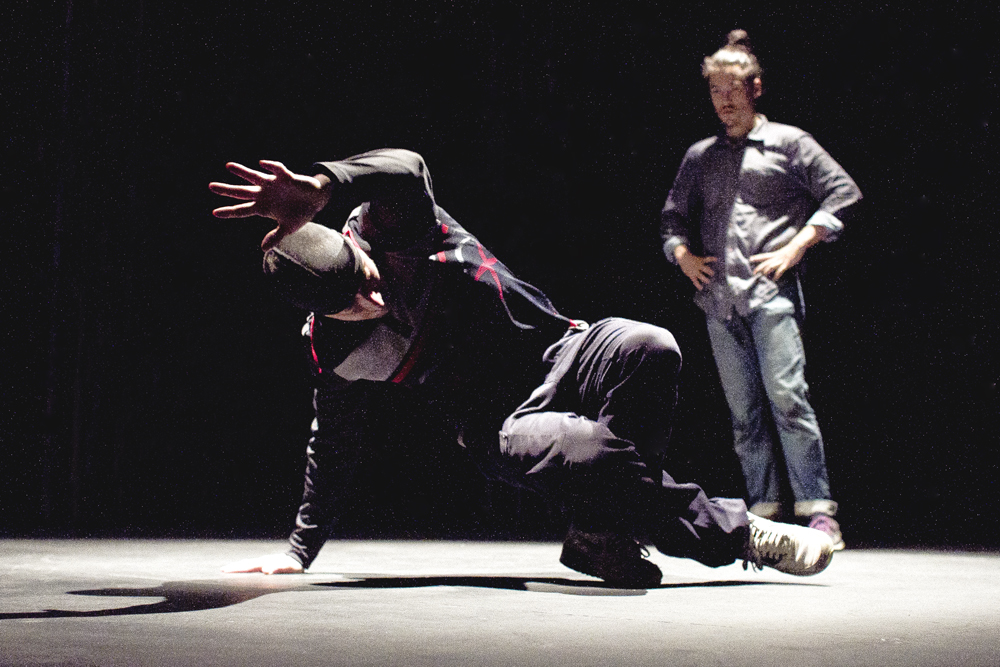

Filming and producing dance films and documentaries is not new to Szporer. In 2001, he and his friend Marlene Millar co-founded the arts film production company Mouvement Perpétuel. The pair’s work ranges from 3D films showing human struggles using contemporary dance in Lost Action: Trace to Leaning On A Horse Asking For Directions, which incorporates BaGuaZhang martial arts and contemporary dance choreography to evoke empathy by watching how performers move and interact with one another.

“We were interested in uncovering the landscape of the body,” Szporer said, regarding the way he and Millar go about filming their work. Their process begins with knowing the choreography to anticipate where the body will be in the space, and further convey a message in the captured movement. Szporer doesn’t describe filming a dance performance as formulaic, but there’s definitely emphasis on the “expressive quality the body can have” in stillness and in motion.

Before Szporer and Millar created Mouvement Perpétuel, they were Pew fellows at University of California in Los Angeles. “This allowed us to go deeply into the area of dance film,” Szporer said. Working with professionals in L.A. and being mentored by professionals from other countries was a great, immersive experience for Szporer. “It was great to be … in this academic environment,” he said. “It allowed us to question ‘how do we want to make films?’ And ‘what kind of films do we want to make?’”

Once Szporer returned to Montreal in the 90s, the pieces fell into place—he and Millar knew how to convey a story through a dance film, and networks in Canada like Bravo! were supporting short-form arts films. The crucial components—the skillset to make quality productions and the demand for dance films— were put in place for Szporer and Millar to build up their production company to what it is today, taking on international collaborations and local projects alike.

Early in his career as a dance commentator and filmmaker, Szporer never had to look too far from the city for fascinating shows and movements. The Montreal dance scene in the 80s was flourishing with local homegrown talent and material.

“Many people were starting out [in Montreal]: the Édouard Locks, the Ginette Laurins, the Marie Chouinards, … I was interested in what they were doing,” Szporer said. In addition to witnessing the then up-and-comers of the dance community, Szporer was intrigued by viewing people’s work in a unique, untraditional way. “You could go to performances in people’s lofts, you could see them in galleries,” he said. “It was inspiring to be in the midst of all that.”

Later, the larger, more well-known post-modern artists “migrated north,” to use Szporer’s words, from New York City. The post-modernists brought a different flair to Montreal’s existing arts scene. Szporer sums up the time perfectly: “You knew you were seeing something key to the development of the form.” Montreal was evolving into a dance hub, with external influences shaping the larger arts scene and homegrown talent creating an established dance community within the city.

Szporer also ventured into an area many dancers shy away from: talking and writing about dance to the general public. He never accepted the assumption that dancers and choreographers can only express themselves physically through movement.

“I am totally of the mind that there are a lot of [dancers] who are extraordinarily able to express themselves with words,” Szporer said. “I believe dancers and choreographers have something to share with people.” Words, especially those describing dance, captivated Szporer.

After working a few odd jobs, including as a “singing telegram,” he started working as a dance columnist on CBC radio during the 80s. This gig allowed Szporer to show listeners dance could be articulated in non-visual ways. “The big thing … you are speaking to many different kinds of people who are not necessarily understanding what you’re talking about, so you have to make it understandable and not sensationalize it,” he said. The radio dance column, alongside writing for other publications like Concordia’s own former newspaper, Thursday Report, plunged Szporer further into Montreal’s dance community.

He still writes for several dance publications, like The Dance Current and Dance Magazine, where he reviews performances and breaks down Montreal’s evolving dance scene by detailing new studio openings, as well as chronicling the city’s dance trends past and present.

These skills, along with his undisputed passion for dance, come in handy as a part-time professor at Concordia. Unlike other faculty members, Szporer teaches four courses between two different faculties. He teaches Dance Traditions and Dancing Bodies in Popular Culture within the Faculty of Fine Arts, and teaches two classes at the Loyola College for Diversity and Sustainability.

“[Teaching] wasn’t something I sought out to do—it came to me,” Szporer said as he remembered being approached in 2002 by Concordia’s contemporary dance department to teach the Dance Traditions course.

Although Szporer jokes about his teaching skills improving over the years, one can’t help but think he’s being modest. His newest class, Dancing Bodies in Popular Culture, which is available to non-fine arts students, is an embodiment of what Szporer has built his career on—talking about dance.

The Culture and Communication course he teaches at the Loyola College for Diversity and Sustainability continues to foster Szporer’s passion of introducing and articulating arts and performances—this time in ways that are “grounded in ideas about the environment and ecology … and general notions of diversity.”

Ideas of diversity struck a chord with Szporer. “Diversity is so fundamental,” he said. “We all have to get on board with developing language surrounding these ideas.” He was thrilled when he was offered another course, which he decided to turn into into a film course: The Future in Film: Ecocide and Dystopias.

In class, Szporer stands away from the podium, centred in front of the large screen behind him, and turns the class into an active discussion where everyone can comment and reflect on elements of dance. Last week’s contentious question: Is striptease considered dance? “The dialogue that happens within the class is fascinating because it’s … a different kind of conversation that begins [when] people ask different questions from within the [dance] profession and without,” he explained.

Perhaps that’s the most enjoyable part of teaching at Concordia for Szporer—the notion of putting forth an idea and being met with positivity and encouragement on the other end. It’s liberating and motivating to be at an institution where there’s always room to grow, he said. Szporer especially enjoys being able to teach students from varied disciplines to be “comfortable with knowing that you are in a big world with lots of richness you can learn from.”