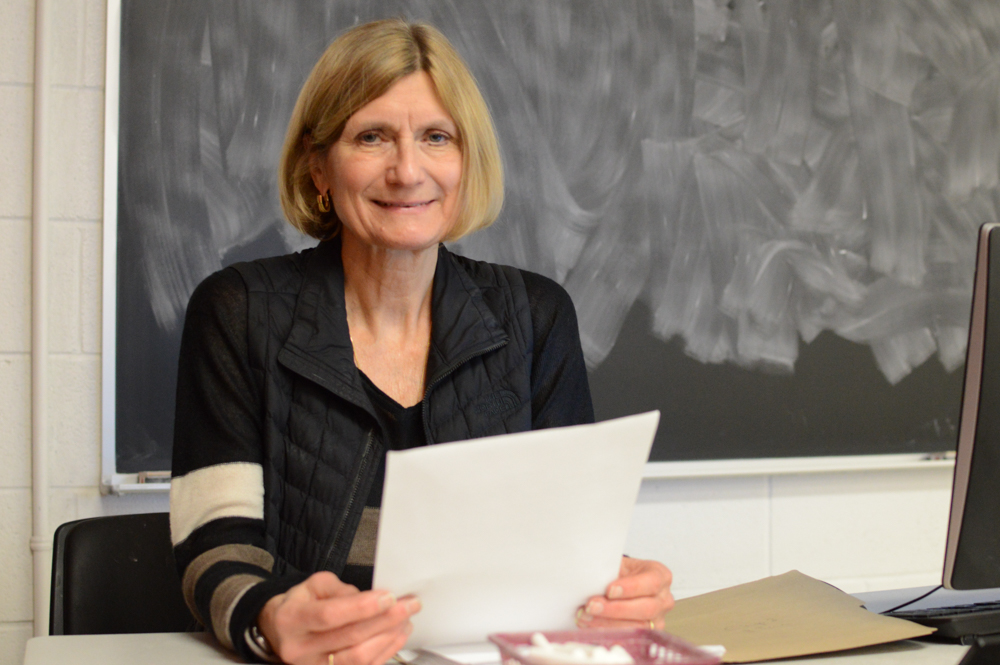

Colleen Gray brings her experience as an editor, writer and poet to the classroom

Colleen Gray was flipping through books at the St-Sulpice Library, searching for a topic for her PhD thesis, when “this person’s voice just jumped out of the book and grabbed me.” It was the voice of Marie Barbier, a teaching nun from the Congrégation de Notre-Dame who lived in Montreal between 1663 and 1739. “I had this feeling I was going to write about this woman,” Gray recounted. “I felt that her voice needed to be heard by other people.”

The book in which Gray first discovered Barbier’s voice was actually written by a male priest who had collected the nun’s writings, inserted them among his own depiction of her story and then thrown away the originals. As with so many marginalized voices in history, what remained of Barbier’s work was fragmented and corrupted.

“That’s what happened to women in history. It’s your classic paradigm of how we’ve lost our voices in history,” Gray explained.

When Gray began studying history at the undergraduate level in the 70s, it was not only the women in history who were being marginalized; little space was provided for the women seeking to study it. This was one of several factors that stopped Gray from pursuing a master’s degree at the time.

She also saw that the field of history was moving away from a narrative discourse and focusing more on quantitative analysis. As a writer and a long-time poet, it was a shift Gray wasn’t willing to make. “That was just a little bit over the edge for me,” she said. “So I thought, ‘Well it’s time for me to step outside of that area.’”

Over the next two decades or so, Gray traveled and taught English as a second language; she edited manuscripts, had children and worked for the Science Council of Canada. In the early 90s, however, something began to change.

“I started to feel like time was running out, and if I wanted to really do something in academia and poetry, I had to do it now,” Gray said. Even her poetry, which she had continued to write and publish over the years, focused on historical themes in Montreal and seemed to demand the footnotes that characterize scholarly writing.

When she returned to university to complete her master’s, Gray was surprised to find that, not only had narrative history made a comeback, but women had also taken centre stage in her field.

“I came back at just the right time,” she said. “The beginning of my PhD was a wonderful adventure, a wonderful exploration in women and women’s voices and women’s archives. It was just such a liberation for me to be able to do that and do that with integrity without hiding it.”

A few years after she completed her PhD at McGill University in 2004, Gray decided it was time to rescue Barbier’s voice as best she could. The process involved transcribing, translating and annotating the nun’s writings to give them context. Compiled in the latter half of Gray’s book, As a Bird Flies, Barbier’s writings tell their own story. For the last three years, Gray has been writing a biographical introduction for the book—an endeavour that has grown from an anticipated 10 pages to nearly 100.

“It wouldn’t have gotten bigger if I hadn’t seen, as I was doing it, […] how much more real she became and how much more we could understand her life if it was presented this way,” Gray explained.

Yet a comparison can be made between the priest’s appropriation of Barbier’s work and the way Gray is presenting the nun’s writings. In fact, it was a realization that slowed down the progress of As a Bird Flies. “I was very judgmental with what he had done when I started the project, but as the journey advanced, I realized that I have no right to judge him because that’s what I’m doing,” Gray said.

The difference, Gray explained, is that she has preserved the integrity of Barbier’s writings in the second half of her book for people to read and interpret on their own. “I didn’t throw her writings away, and I tried to be as true as possible to the original source as I encountered it,” she said. “It’s corrupted, but the fact remains—and this is something that is difficult to prove—you can hear her voice.”

Part of the challenge has also been striking a balance between historical accuracy and an engaging narrative. “It’s the hardest thing I’ve ever had to do,” Gray said with a laugh. “I just reach a point where I can’t do it anymore, and I have to do something else.”

For Gray, there is always something else to do because the trajectory of her career has allowed her to remain “diversified,” as she put it. Although completing her master’s and PhD later in life didn’t make her an ideal candidate for tenure, Gray said that path “wasn’t in the cards” for her anyway. Instead, she has worked as a part-time professor at Concordia since 2006, and also taught at Queen’s, McGill and Nipissing University in North Bay, Ont.

Most of the courses she teaches—including her pre-civil war American history class at Concordia this semester—are what she refers to as “survey courses.” Typically assigned to part-time professors, these classes take a broad look at long periods of history and have allowed Gray to diversify her own expertise.

“Now, I’m no longer this 17th century PhD specialist,” she explained. “I have really a broad, expansive understanding of North American history—both American and Canadian perspectives—and history from women, from natives, from different ethnic groups.”

Unfortunately, cutbacks in education in general have significantly reduced the number of courses available to part-time faculty in the history department, Gray said. The last course she taught was in 2016. While her freelance writing and editing offer her other sources of income, “it’s very difficult to rely on being a part-time faculty member,” she admitted. “It’s inconsistent and it’s insecure, but it has its advantages too.”

Gray said she enjoys being able to teach and still have time to work on her poetry and her freelance writing and editing. “You get to develop yourself outside of that box,” she said. It is this ongoing personal and professional development that can make part-time faculty members a unique asset to students.

“Many of us are not mainstream academics,” Gray said. “I have one side of me that is, but I’m a poet, I’m an editor. I have a lot of these different dimensions that I do bring to the classroom.”

She added that she feels her “roundabout journey” to the academic world is a valuable life experience she can share with her students. “When they come to me for help with their essays, you can’t help but talk to them about what they’re going to do and what they want to do and if they feel they should be doing history,” she explained. What Gray said she hopes students can learn from her experience is to see the bigger picture.

“It looks so difficult when you’re young. It seems so narrow, and there don’t seem to be any openings,” she said. “Maybe at the moment [history] is not for you, but that doesn’t mean 10 years down the line it’s not going to be. […] People change directions all the time, and it’s not looked down upon.”

Although these interactions allow Gray to mentor students to a certain degree, she said part-time professors are limited in the work they can do with students outside of the classroom. In particular, she said the fact that part-time faculty are not allowed to supervise a master’s or PhD thesis is “a huge restriction” for her.

“I feel I am very qualified to do so, and I feel stifled by that [restriction],” she said. “It’s understandable, because I’m not working sometimes, but so what? I would continue to supervise somebody’s work even if I wasn’t teaching just because I’m interested in it.”

For Gray, being interested in the subjects she engages with is a driving force for her work. “Writing is always a headache,” she said. “But it can be so invigorating as well, if you get the right project.”

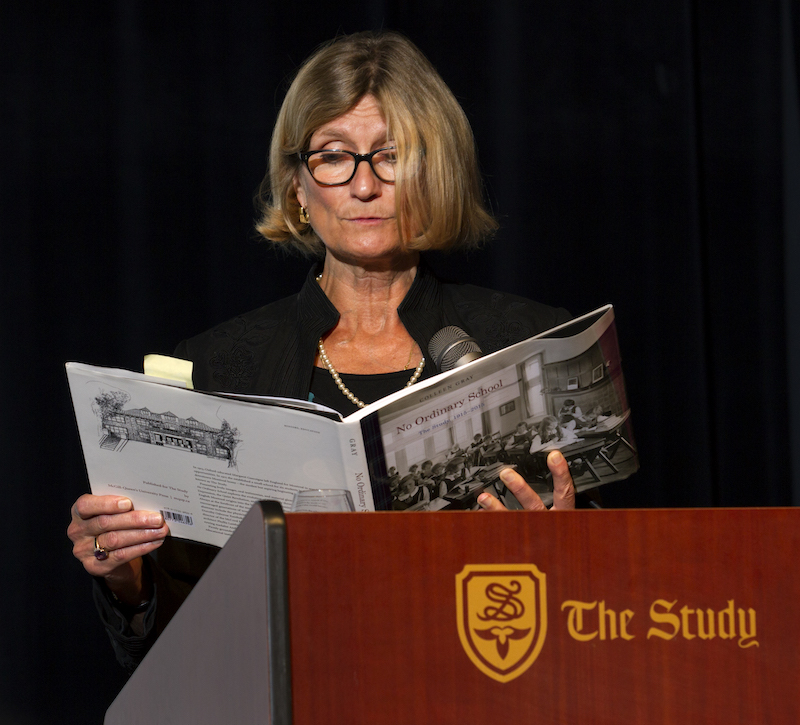

This was the case for a book Gray wrote in 2015 as part of the centennial celebrations of The Study, a Montreal private school. “It was like the Marie Barbier project,” Gray said. “It jumped out at me that I wanted to do this project.”

The result, No Ordinary School: The Study, 1915-2015, “was a two-year, huge, under-the-gun project,” Gray recounted. The process involved sifting through old student newspapers and the school’s archives, as well as speaking with former students, teachers and headmistresses.

“There were 90-year-old women with wonderful memories, and they could give me the history of their school and what it was like during World War II,” Gray said. “One person could even go back as far as the 1920s.”

Part of what kept Gray engaged as she rushed to meet her deadline was the connection she felt to the women she was writing about. “It was almost like reliving my girlhood as a privileged private school girl,” she said with a laugh. While some people may have perceived these students as snobbish, upper-class girls, Gray didn’t approach it that way.

“I saw it as having a wonderful girlhood where you had the best education that was available for women at that time,” she explained. “I looked at it from a different angle, and stepped into those shoes.”

For Gray, being able to put herself in her subjects’ shoes and immerse herself in the material is crucial. “I wouldn’t take up a project unless I could do that, because it’s fun,” she said. “If it’s a project where you don’t want to put yourself into it like that, then that’s for somebody else to do; it’s not for me.”

..

At the age of 10, Colleen Gray discovered poetry. It was the spark for her career as a writer. “[Poetry] is something I’ve always had, that I’ve always done,” she said. Gray’s poems have appeared in literary journals such as The Canadian Forum, Zymergy and Fiddlehead, and she has performed her work at venues like the Yellow Door.

Consolidating her interests in history and poetry did not come naturally to Gray at first. “It took me a while to see the two of them merge,” she said. Although Gray has experimented with confessional and political poetry, historical topics often become the focus of her poems. “It’s not strictly history—it’s interpretive history,” she explained. “[The facts] are still there, but you can play with them a little bit more.”

Atironta, ca. 1650 1

(I am Atironta, son of mighty warriors)

… and in the silence of the night I pray

to you my Holy Mother, Blessed Virgin

my lighted

candle flickers in wind howling through the bark

of our longhouse and beyond the forests, above

the pine trees rushing into the mist of a thousand

cataracts I follow the wind to our home

Huron Land

(Holy Mother, Blessed Virgin, save us)

… our dead are strewn beneath the earth

their groans echo in my prayers –

you have not released our souls

to our Villages of the Dead

Atironta, mighty warrior

- Loosely based on a historical person, Pierre Atironta, survivor of the dispersal of the Hurons by the Iroquois in the late 1640s, appearing in Reuben Thwaites, ed., The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents (Cleveland: The Burrows Brothers Company). Published in Matrix: Writing Worth Reading 32 (Fall 1990): 37.