A lifetime of lessons

Born in 1929 and now residing in Montreal, Irene Steiner is an extraordinary woman; she is the culmination of vast and tremendous travel, violent and painful hardship, and a relentless devotion to learning. Steiner, Somogyi and Even are all last names acquired from different points in time, stemming from varying circumstances, yet belonging to the same person. Her life stages correspond to her different names, creating a map with pins that connect her long and arduous path. Much like her collection of names and identities, Steiner’s story is a vast one.

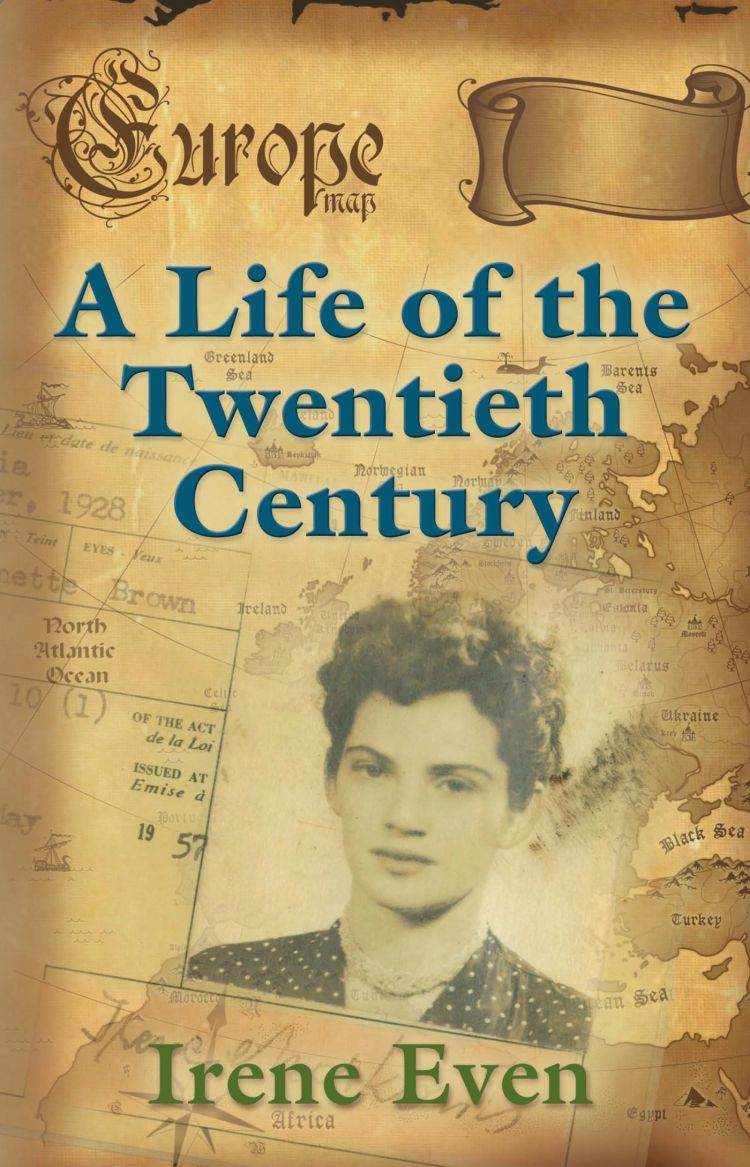

Steiner, whose pen name is Irene Even, detailed her life story through the perspective of a protagonist named Aya in her book titled A Life in the Twentieth Century. According to the Montreal Times, she is the oldest living university graduate in Montreal having completed three undergraduate degrees. She still attends continuing education classes at McGill. Learning and educating throughout her life has fulfilled her through trying times, and she continues to advocate for education.

Steiner was born in Nagyfalu, Hungary, a Romanian village before Nazi occupation. Her parents died when she was three, so Steiner grew up under the care of her grandparents. In September 1941, she began boarding school in Budapest.

Initially, Steiner was reserved and shy, but through reading and learning, she began to find herself, becoming the energetic, curious and passionate person she is today. In the spring of 1943, Hitler’s fleet marched into the heart of Budapest, leaving Nazi posters everywhere. “They looked like robots. And of course they were not human. They were robots in effect,” Steiner explained in an interview with The Concordian.

Hungarian authorities executed Nazi law with enthusiastic malice, even more than the Romanians. Gestapo-issued edicts calcified fear in the branded stars and the people who wore them.

Bombs fell from British and Russian planes, leaving Budapest destitute. Explosions set the ghastly, dissonant rhythm of the city, a song leaving the dead and dying scattered in the streets. It was the first massacre of the Holocaust to reach a five-figure casualty count.

Students at Steiner’s school were sent home, but she was one of the few left unclaimed and forgotten. She sought refuge with representatives of a Zionist movement, who taught Jewish people how to survive the regime and provided resources to do so. Steiner was given false papers that labelled her a Christian named Somogyi.

Russian liberators freed Budapest from the Germans, yet enslaved them as their own. Some surviving Jews showed their yellow stars with the hope of better treatment, only to be labelled capitalists and enemies of socialism and sent to Siberian work camps. The Russians were no better than the Nazis.

A line from Steiner’s book reads: “True, she had survived the horrors of Nazi rule, but there was no celebration; her heart was void of emotion in the face of the universal hunger, the naked fear on the face of people.”

Under the guidance of Palestinian Zionist representatives, Steiner was indoctrinated with socialist ideologies. Unfazed by the Soviet oppressors, Steiner dreamt of going to Palestine to build a Jewish state with Russia as its model and Stalin its hero. She lived in a kibbutz (a communal settlement) with fellow survivors in Transylvania for five months, each day hoping to begin their journey to Palestine.

Disguised as Czechoslovakian refugees, Steiner and her group fled from Austria to Italy through the Alps. On foot. The group was relieved when they reached the Jewish Brigade in Italy, which led them to Palestine. The Brigade is where she met Mort, a Hungarian-speaking soldier who took interest in the pilgrimage and in Steiner.

Steiner was coerced into a toxic marriage. “He was jealous of the air I breathed,” she said. Her young adult years were spent serving Mort, who treated a self-fabricated illness with a drug addiction. Surrounded by pain, Steiner’s optimism cut through the dark as she recalled a good life: “We had money, we had two beautiful houses.”

Steiner and Mort moved to Montreal in 1952. “My unhappiness was so deep in me that one day I just collapsed,” she said. She described her home as the “infirmary to battle zone,” but she vowed not to remain a wounded medic. Steiner went to school, rekindling the passion that sparked in Budapest. “My formal education really started after [I was] divorced,” she said. A new liberation prompted her love for learning and teaching. “It was the first thing in my life that gave meaning,” she said.

After completing her studies, Steiner spent 22 years teaching in Sderot, a small village in Israel (formerly Palestine) before retiring in 1997. Her passion and love for learning made Steiner an incredible educator. “The nicest years of my life were in teaching,” she said. When asked if she could label a quality that exists in every great teacher, she instantly said, “Absolutely! You have to believe that those kids can learn.”

The name ‘Steiner’ is Bavarian (‘Even’ is the Hebrew translation); it refers to a person who resides near rock. Steiner’s surname draws parallel with her resilience and grit, as if she took pieces of mountains and incorporated them into her character. Her life is chaptered in three, the Carpathians, the Alps and Mont Royal representing her birth, growth and retirement. In light of this, it is most fitting that Givat HaShlosha, the kibbutz she lived in during her exodus to Palestine, translates to “hill of three.”

Author’s note: some names have been changed throughout Steiner’s book to omit their identity.

Feature image courtesy of interviewee.