Come away and Reset with me

“Someone once said it is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism.”

This quote, taken from Fredric Jameson’s “Future City,” given the current state of global affairs, might feel more relevant than ever.

On March 11, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a global pandemic and in just under a week, it ushered in a new era of social distancing. This article, originally conceived before the pandemic, was intended to pique the reader’s curiosity about the exhibit (and unintentionally the COVID-19 curve). So instead, we invite you to venture beneath the downtown core, into the underground city and visit Art Souterrain, a public art exhibition, from the comfort of your own home.

Art Souterrain’s 2020 theme Reset showcases art as a response to “humanity at a turning point.” Up until last week, the COVID-19 pandemic felt more like a distant possibility than a pressing reality.

It is true that many people, pre-COVID-19 crisis, had already seen the world at a tipping point, one that cried out for massive intervention. People were in the process of reorienting their own courses, avoiding the onset of environmental extinction, fighting the privatization of public services, protecting Indigenous lands or even preparing for an inevitable pandemic.

And yet now, all of our active, externalized and productivity-focused lives have abruptly come to a halt. We’re seeing the collapse of already precarious economic and healthcare systems, extensive financial turmoil, extreme physical isolation and a move to bring the real world, more than ever, online.

Social distancing is certainly in our best interest. And while we remain secluded, our pace will slow. We might have the time to rethink, reimagine and reset our social patterns and behaviours.

And although a visit to The Underground City is not condonable under the current circumstances, perhaps this piece will soothe your needs to escape the confines of your home while you embark on a virtual tour, highlighting the contributions of Concordians at Art Souterrain.

On March 7, I googled 10,000 steps. “Should you really take 10,000 steps a day?,” a headline for a click-bait “article” posted on the Fitbit—a popular and elite fitness tracking device—Get Moving blog was the first thing to appear. The content of the article meant little to me so I decided to skip over it. Its content is irrelevant, but what the article represents is what matters.

The commodification of fitness, 10,000 steps, is movement to quantify health habits and include them in daily assessments of productivity. Measured on your smartphone, Fit Bit, or other costly technical devices, 10,000 steps symbolize a bourgeois obsession with the analysis of a daily routine. These very devices are marketed towards the white-collar class as objects that define a productive, wealthy, and superior lifestyle.

RESO or the Underground City is Montreal’s subterranean labyrinth. It’s a highly developed, intricate, permanent network that on a regular day, is a transitory space for the bulk of its regular users; a site where Montreal’s establishment clock in their daily steps en-route to meetings, brief errands and quick lunch breaks.

It’s a conduit between the largest shopping malls, banks and businesses in the city. A site of convenience, and rather pedestrian in nature—both figuratively and literally—a patron of the Underground City may never have to leave the indoors to transfer from one building to the next, making their life simpler, shorter and more efficient.

Walls of the tunnels are plastered with posters of advertisements, interactive marketing strategies, TV advertisements and out-of-date pop music blaring through speakers. Some walls are long stretches of wide spaces with small storefronts selling luggage, computer items, gaming paraphernalia, customizable t-shirt stores or food courts armed with a visual grammar all too ubiquitous and familiar.

In a narrow, grey, hallway between L’OACI and Bonaventure Metro, five human-like forms clad in geometrically painted pylons lay scattered intermittently throughout the space. A few wear them like hats and look like witches. Others carry them like a javelin, resembling medieval knights on horses.

Gab More’s One Cone Army reinvents painting as a medium, using it as a sculptural street sign, occupying physical space. More’s signs stick out like sore thumbs, obstructing a hurried pedestrian’s path, reminding us that our city remains in a constant state of disarray.

From a distance, they look like war photographs you’d see at the World Press Exhibition: piles of rubble-strewn bodies, clouds of fire, mass armed conflict. At a closer glance, one might think it’s piles of debris leftover from the Turcot Interchange.

It is neither. Using digital manipulation, artist Sean Mundy has created Ruin, his own interpretation of a post-apocalyptic world. These austere images are concepts of a dystopian future. But their visual grammar is familiar, and the thought of a cataclysm doesn’t seem so distant either.

By the large fountain in the Centre de Commerce Mondial, a wedding party poses for bridal photos. Throughout the space, tour groups gather to learn about Canada’s parliament pre-confederation. Supposedly, this experience also functions as an escape room.

Surprisingly, none of these are performance pieces, they’re not part of Art Souterrain. These groups are the Saturday crowd.

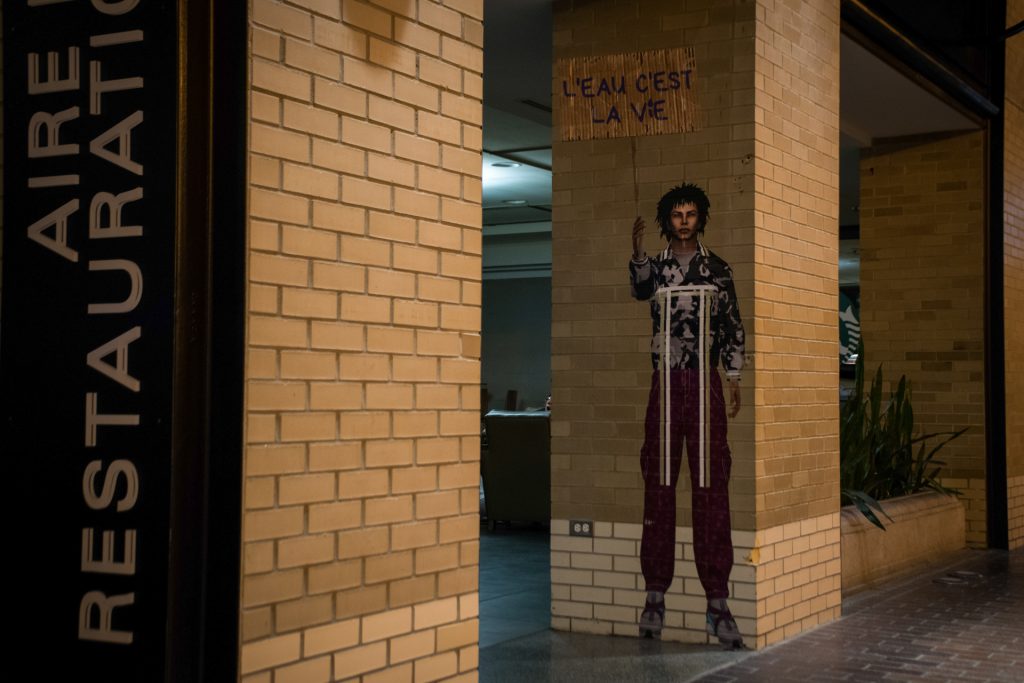

Throughout the centre, plastered on brick pillars and marble walls, are life-sized digital avatars. They carry protest signs with phrases such as “I can’t believe we have to protest this shit” and “Water is life.”

Skawennati, a Mohawk multi-media artist, brings visions of Indigenous futures developed in virtual reality to be as large as life in the form of plastic wall decals. Covered in neon camouflage vests, cargo pants or skirts, they look like computer-generated images used in a rendering of a condominium development or the Sims. But they’re the opposite of that. This is Calico & Camouflage: Assemblée.

Skawennati still arms the space with viewing stations, a style more evocative of her traditional work. On TVs, you can watch her films Words Before All Else Part I, II and III. Her videos are powerful, but it’s the figures on the wall that are eye-catching. They are what Skawenati says is a form of “visibility in spaces of assimilation.”

In a quiet corner of Palais des Congrès, Montreal’s largest convention centre, lies a beige mission-style bench. It looks like a giant extended rocking chair situated beneath a reflective ceiling.

Arkadi Lavoie Lachapelle has created La Chorale, resistance against “productivity centred” lives. Its form is simple, its message is subtly disarming: sit down, relax, disconnect from your daily routine and rethink.

Warm pastel portraits decorate the walls of a tunnel leading towards pension fund investment offices in Edifice Jacques-Parizeau. JJ Levine’s Family is quietly on display.

The shots are soft meditations into intimate private lives. A parent and baby are asleep, covered by magenta sheets, lying in a bed beside a bright orange wall. A soft pink backdrop, grey couches and a young couple in jungle-print t-shirts hold hands. A toddler sits in a baby-blue jumper on turquoise stairs, their piercing gaze pointed directly towards the viewer. A parent breastfeeds their baby in a floral-print gown seated on top of a chestnut coloured storage trunk.

Family is a series of portraits of queer family life, made visible in a space that represents traditional values. Levine boldly subverts images of the nuclear family and claims them as their own symbols of family life.

In front of a Van Houtte Café in Palais Des Congrès are a series of perfectly arranged white cubes protruding diagonally into the air. At the top of the cubes lie charcoal coloured, miniature mountains. This topographical sculpture is Elyse Brodeur Magna’s Un Tout Parallèle.

Applying thought from Greek philosophers, Lucretius and Epictetus, Un Tout Parallèle suggests that when atoms deviate from their parallel path, they create new physical bonds; in turn, new forms. Although uniform in their style, these sculptures are products of fresh physical creations, and invitations to climb the mountain in search of a restored purpose and a new physical form.

Tough times are certainly ahead, but how do we transcend them? Perhaps Un Tout Parallèle leaves a hint.

“Eat, Sleep, Game, Repeat. Eat, Sleep, Game, Repeat. Eat, Sleep, Game, Repeat.” This routine, or rather, this mantra is the modus operandi for the stereotyped gamer. Using performance and installation, artist Maxime Loiseau propels the imagined reality of the disconnected gamer into the real world.

Occupying a storefront opposite a food court buried beneath Place Victoria, Loiseau has created a life-sized diorama. It resembles a gamer’s basement, covered in gaming paraphernalia, junk food, used pizza boxes, with clothes strewn across the floor. This is Bac à Sable, giving the public a voyeuristic view into virtual life.

It’s a reference to geek culture and comment on overconsumption. But as we retreat into cloistered lives for the foreseeable future, gaming might be the antidote to reimagine the reality we’re facing.

This is where I end my 10,000 steps, in a food court in downtown Montreal, decorated like a 1990s shopping mall. Its shabby decor is a fitting backdrop for Reset and its exploration of urban obstruction, public display of private life, productivity culture, questions of alternate futures and transcendentalism.

This reset is an artistic form. We’re in a state of reset, but don’t know what it looks like yet. Our lives are slowing. As we retreat inside for society’s betterment, there are barriers that inhibit one from collecting their 10,000 steps, but the pressure to do so might also be dwindling. If anything, when we make our way out of it, hopefully, we can take these messages to heart and reset our daily lives.

Photos by Anthony James Armstrong.

Video by Lola Cardona.