The five-day festival was part of a larger global screening aimed at drawing attention to the intersection of pinkwashing, queerness, and the nuances of Arab identity

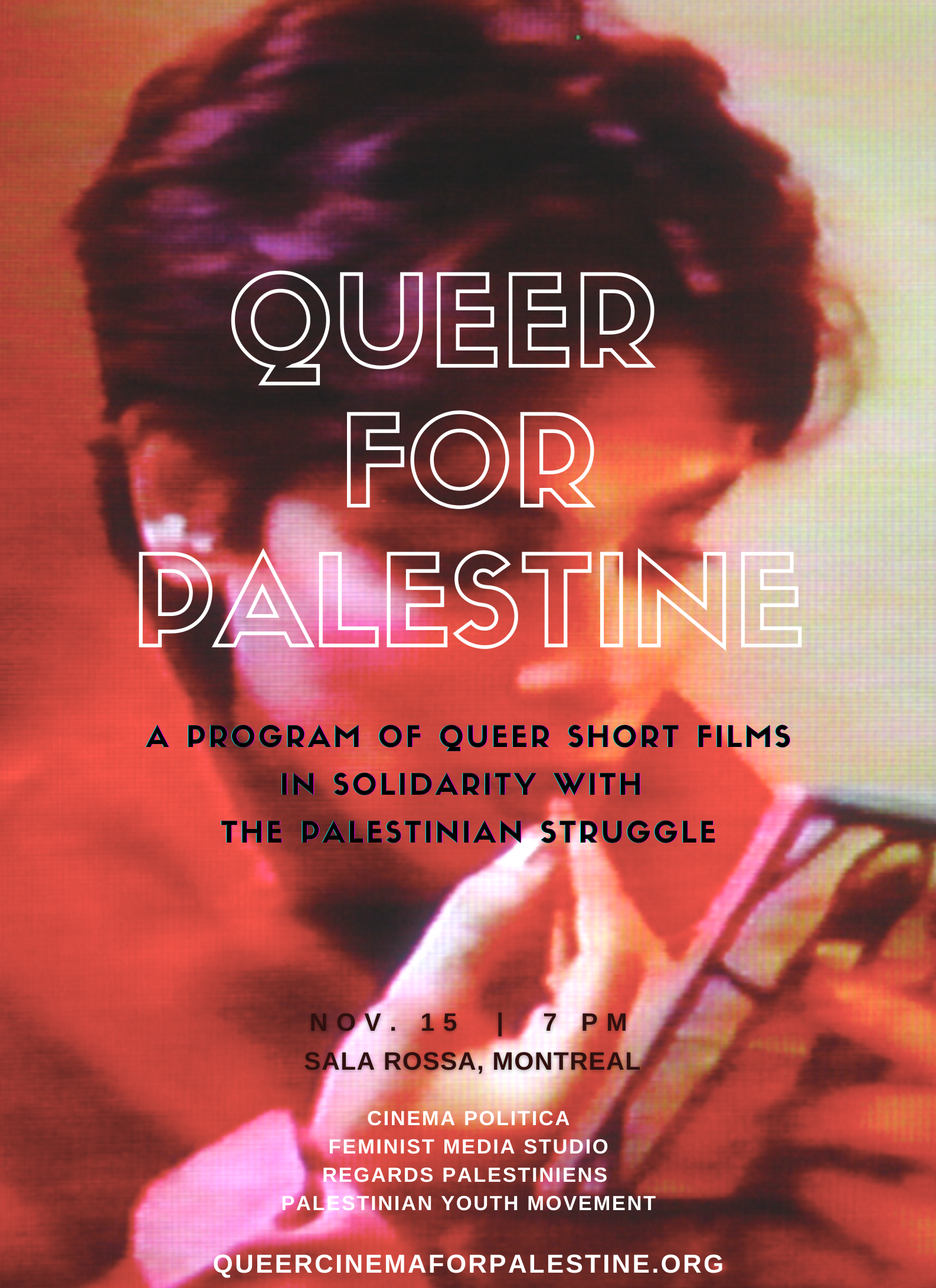

Four short but powerful films composed the Nov. 15 screening at the Queer for Palestine film festival at La Sala Rossa, located at 4848 Saint-Laurent Blvd.

Spanning from six to 41 minutes long, the films, in order of appearance, were Houria (2011) by Raafat Hattab, Blessed Blessed Oblivion (2010) by Jumana Manna, Mondial 2010 (2014) by Roy Dib, and Cinema Al Fouad (1993) by Mohamed Soueid.

With films chosen by members of Regards palestiniens, a Montreal collective composed of researchers, artists and activists, the festival was meant to raise awareness and celebrate the experiences of queer Arabs, in solidarity with Palestinians and as a part of the global festival, Queer Cinema for Palestine. The collective aims to organize cinema events that draw attention to the multifaceted lived realities of Palestinians and highlight the community’s creativity and engagement. Cinema Politica and the Feminist Media Studio were involved in the production as well.

The curators of the Queer for Palestine festival were Farah Atoui, Razan AlSalah, Muhammad Nour Elkhairy, and Viviane Saglier.

Speaking as a collective to The Concordian, the curators explained the rationale behind the choice of films. “We were looking for films that explore sexual and gender identity as part of the larger struggle for Palestinian liberation. […] These films expand queerness beyond an individual or collective identity into a political life project. These films also retell Palestinian history from a queer perspective.”

La Sala Rossa has a history of hosting progressive cultural events, beginning in the early 1930s as a gathering place for the left-wing Jewish community in Montreal.

The Nov. 15 live screening was followed by a discussion hosted by members of the Montreal chapter of the Palestinian Youth Movement, a grassroots organization of young Palestinians and their allies dedicated to the liberation of Palestine. Colonialism and western imperialism were discussed in relation to the films, as well as the intersecting experiences of queerness, Arab and Muslim identity.

The choice of short films versus long ones was conscious on the curators’ part, aimed at fostering conversation. “We hesitated between a long-feature and a program of shorts. We opted for a program of shorts because it offers a diversity and multiplicity of perspectives, as well as presents different aesthetic approaches, and thus makes for a richer and more layered reflection and discussion.”

The film festival also had a virtual component: the screening was available online until Nov. 20, featuring a pre-recorded discussion between two of the filmmakers, Dib and Hattab.

Queer Cinema for Palestine also hosted screenings worldwide from Nov. 11 to 20 partially featuring works from Palestinians, North Africans, and South-West Asian directors and artists. It spanned five continents, the virtual world and the physical one, as well as the line between film and documentary. The festival, in its first edition, was a 10-day long queer solidarity initiative that used art to combat the violence of Israeli apartheid and pinkwashing.

Pinkwashing is a form of propaganda that portrays (in this context) the Israeli government as being inclusive to the queer community (in contrast to the Palestinian government), though that isn’t necessarily accurate to reality.

The festival was meant to “offer a space for artists and filmmakers who have pulled their films from TLVFest, a government-sponsored LGBT film festival that plays a key role in pinkwashing Israel’s regime of military occupation and apartheid. The TLVFest portrays Israel as [a] safe haven for queer folks while justifying the oppression of queer Palestinians,” explained the curators.

The stereotype of Arabs and Muslims as being anti-LGBTQIA2S+ has also been employed in relation to pinkwashing efforts by the Israeli government. Western media doesn’t proportionally highlight these groups, which in turns help to support the Islamophobic propaganda that positions queerness and being Arab and/or Muslim as totally non-existent. Initiaves like the film festivals help to counter pinkwashing by showing that not only do queer Arabs or Muslims exist, but they are mutli-facted within those categories.

Houria by Raafat Hattab was perhaps the least accessible in terms of its message. It was the shortest at six minutes, and the emotional scenes featuring Hattab’s grandmother, Yousra, were more compelling than the conceptual ones featuring a merman on a beach. These were meant to explore his conflicting feelings surrounding identity, in part due to the family’s displacement during the 1948 Nakba. Yousra, who came across as strong and sympathetic, detailed how she was expelled from the village she’d grown up, Jasmeen Al-Garbi, by Zionist paramilitary.

Blessed Blessed Oblivion by Jumana Manna was the standout of the festival. Her film combined visual collage and documentary techniques to create a powerful portrait of masculinity in occupied East Jerusalem. Manna entered into spaces usually occupied by males to film, and the result was an interesting, thoughtful, and at times satirically funny comment on the way men behave around women, and the expression of gender roles in the Arab world. The musical score was notably fantastic, opening with “Ya Raytak (I Wish of You)” by Uthanyna Al Ali, a slow, slightly sinister track that helped to ground the opening scenes of visual collage.

Mondial 2010 by Roy Dib was interesting and touching in a way that left it living in my mind days later. It featured a Lebanese gay couple travelling through Ramallah, an occupied town in Palestine. A feeling of unease was present throughout the film, in part connected to the character’s experience of colonialism, by the military policing of the Israeli apartheid state. While the characters are not Palestinian, they are queer Arabs who also face abuse and discrimination in occupied Palestine.

Mondial 2010 was also an example of excellent filmmaking, because it was able to elegantly translate an ephemeral, hard to pin down feeling of loneliness and disconnection around someone you love.

Cinema Al Fouad by Mohamed Soueid was unlike any film I’d ever seen before in terms of subject matter. It was a touching and personal portrayal of a Syrian trans woman trying to raise funds for a gender affirming operation. You see her as a cabaret dancer, soldier, and then in certain other scenes, smoking sensually and intimately at the camera, sharing her experiences of being gender non-conforming. Definitely the sort of film that makes you remember why documentaries are so important, while also feeling more like a portrait has been painted than a subject ‘captured’ by a distant, uncaring documentarian.

The curators shared what they wanted the public to take away from the festival. “It is our hope to generate a more nuanced conversation about queerness that steps away from the individualist identity. By highlighting Palestinian and Lebanese artists and filmmakers, we want to foreground queerness as an act of self-determination that is inseparable from the larger social and political context.”

Photo courtesy of Mohamad Soueid (Cinema Al Fouad – 1993)