How does the Canadian perspective of Afghanistan relate to reality?

Afghanistan was at the forefront of media coverage in August and September as the Taliban seized Kabul. Yet only three months later — with the country on the verge of collapse — we see few headlines devoted to the humanitarian crisis exacerbated by decades of foreign invasion.

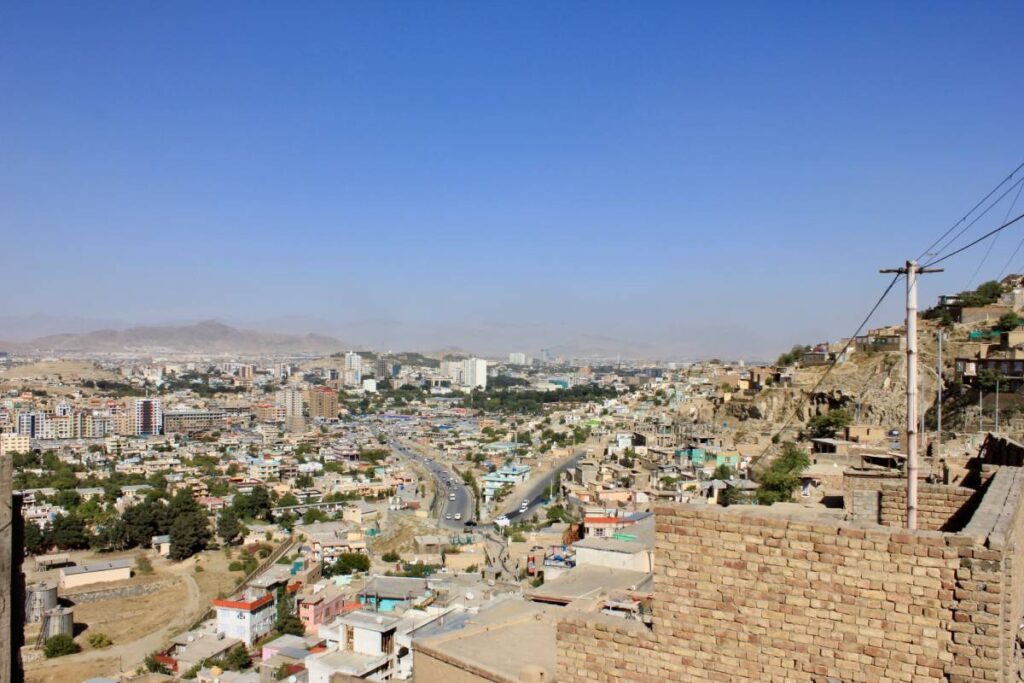

In September 2020, I had the opportunity to visit Afghanistan. While I could not ignore the risks associated with an active war zone, I wanted to see the country for myself, beyond the death and destruction central to Canadian media coverage. When I arrived in Kabul, my western perspective was immediately challenged. As someone who grew up in Canada, I relied on the news to relay information from overseas. So, I asked myself, why was I so surprised to see bustling markets and colourful homes rather than buildings reduced to rubble? It made me think — what do we Canadians really know about Afghanistan?

Canadian media coverage of Afghanistan is focused almost entirely on politics and military developments, rarely depicting civilian life. In part, this kind of reporting is fuelled by the sources used by journalists and the stories that come out of them. In a meta analysis of news articles published during the intervention in the country, nearly half the stories cited military and government officials as primary sources, and over 40 per cent did not include a secondary source.

The Canadian military has a vested interest in selling its success to the Canadian people. The easiest way to do so is by framing the information given to the media in a way that justifies the military’s operations in Afghanistan. While journalists do fact-check and challenge officials, this preferred narrative remains key to coverage of the conflict.

One way to get close is through embeds — journalists attached to military units. The process is far from impartial, as any reports from within an embed must be signed off by commanding officers.

Naturally, no incriminating information would be allowed to leak. Graeme Smith, once a foreign correspondent in Afghanistan for The Globe and Mail, recounted how the military soon became concerned with spin, sending out supervisors to accompany the journalists. Given this element of censorship, embedded journalists seem to serve solely as a military mouthpiece.

The majority of stories reported from Afghanistan favoured a top-down outlook. The problem is that there needed to be a variety of information that went beyond the military and political elite, in order to challenge the propaganda that promoted Canada’s presence in Afghanistan.

With the declared “War on Terror,” perceptions of the Islamic world began to shift. Afghans were vilified and the country was referred to as a failed state. In 2001, the National Post published an article by Mark Steyn titled “What the Afghans need is colonizing.” Alienating Afghanistan served to bolster Canadians’ support for the war and the atrocities that awaited. Inciting fear among Canadians — perpetuated by the media — permitted the government to disregard Afghans’ safety in the name of our own security.

Canadian reporting about Afghanistan is often episodic. It recounts a specific incident, usually involving death tolls and insurgency attacks. Canadian media lacked the context necessary to provide readers with an in-depth understanding of a conflict dating back to the ‘80s.

At the peak of the conflict in the late 2000s, with millions of dollars being poured into the country, why was only one Canadian journalist stationed there full-time? Smith was the only permanent reporter through 2006 to 2009, spending most of his time in the southern Taliban stronghold Kandahar. There is a revolving door of journalists covering the war in Afghanistan, yet few have the longevity to truly understand its implications.

Politicians portray themselves to be the only sources of correct information, leaving Canadians with a misrepresented understanding of Afghanistan. Readers are forced to assume the responsibility of piecing together fragments of a much bigger story.

Despite best interests to accurately portray the conflict, the country has long been ostracized by both politicians and the media. An overwhelming majority of stories reported in the 2000s were rooted in negativity, focused on the volatility and chaos of Afghanistan. A small portion was considered neutral, the positive stories nearly negligible.

News coverage has to do with proximity. When compassion only extends so far, journalists must seek out ways to connect readers to Afghanistan. Any human interest pieces coming out of the country must connect back to Canada in some way — refugees landing in Toronto, a translator to the Canadian Forces — and, usually, mentions the military.

In the end, people are drawn to disaster. Suicide bombings and military advancements are far more likely to captivate readers than a feature on an Afghan school for young girls. But playing into shock value inevitably slants coverage. While focusing on violent incidents may increase engagement with Afghanistan, it reinforces the narrative that the country is no more than a dangerous terrorist den.

When media coverage strips away humanity, it further alienates Afghanistan and its people from the international community. The stories told from Afghanistan favoured the Canadian perspective, failing to paint the bigger picture — 13 years of war and bloodshed. The Taliban’s road to reclaiming Afghanistan was paved by foreign intervention and its failures. Now, Afghans are left to fend for themselves and Canada has already turned the page.

Photos by Kathleen Gannon