The award-winning romance fantasy is a perplexing experience

If you had to choose an animal to be turned into, a lobster would be a fine choice—they live up to a hundred years and remain fertile far into their old age. That’s what David’s (Colin Farrell) reasoning is, anyways. Of course, he forgets that a lobster’s life is likely to be cut short by a gourmet’s appetite for seafood, but that’s part of the joke. The Lobster, which is full of such sarcasm, is a stunningly bleak and bizarre dark comedy from Greek director Yorgos Lanthimos. It seems to be the work of a man deeply hurt by love or offended by the way it is regulated by society, and desperate to get his revenge, even if in cinematic form.

The title is not metaphorical—David may actually get turned into a lobster. The world seems to have regressed into a near-fascist system in which single people are no longer tolerated. All single people must be transported into a hotel in which they are given a set number of days to find a suitable life partner, or—and this is where the fantasy element of the story comes into play—be transformed into an animal of their choice.

Life in the hotel is conditioned by a number of entirely absurd rules, the most notable of which is that lovers must share a common trait—if one suffers from nosebleed, so must the other, if one is a sadist, then the other one must be the same. That makes little sense, as a sadist-masochist couple would logically be better suited for each other, but there you have it.

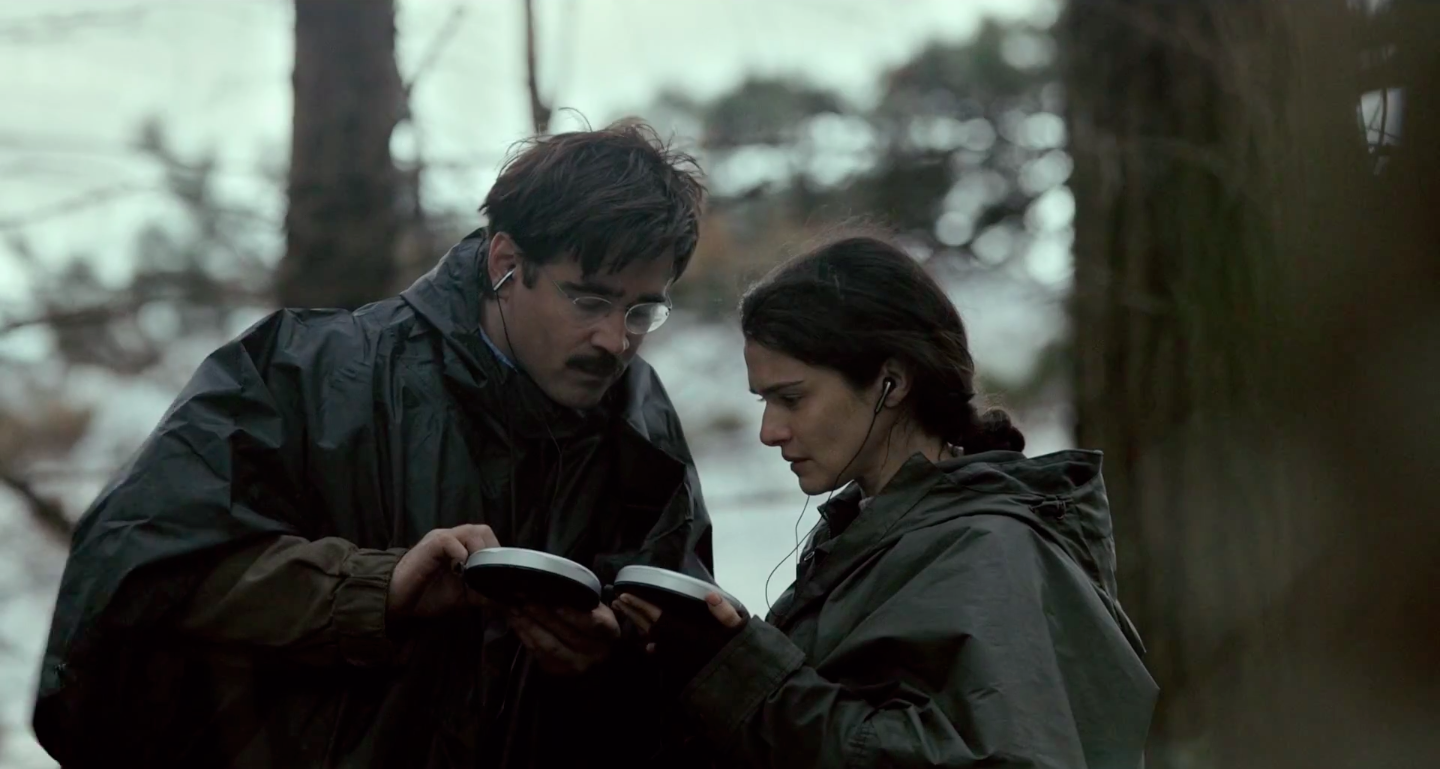

If these single people refuse to comply, they become Loners, hiding in the woods from collective hunts led by inhabitants of the hotel. Life among the Loners is equally hard—they entirely reject coupledom, and so their rules are based on abstinence. Any kind of intimate contact is forbidden, and people who kiss shall have their lips removed. It is then predictable but sadly ironic that David shall fall in love with one of their own.

Remarkably, actors succeed in explaining the specifics of this world with a straight face, but then again, that’s the only mode of acting you’ll see here. Obviously a stylistic choice to amplify the dogmatic nature of this environment, it soon backfires, reducing the film to a one-note exercise in facile cynicism. Most regrettable is the waste of an impressive cast that includes John C. Reilly, Rachel Weisz and Léa Seydoux. Farrell himself as the leading man is not permitted to display emotion, performing mostly by way of his mustache. You might wonder what the mood was like on the set, and the number of rules by which it was itself regulated.

In portraying different forms of torture on screen, a film must be careful not to become torturous to the viewer, which this one, just like the director’s previous drama Dogtooth, ultimately becomes. Violence, more often suggested than shown, here feels like a cheap psychological tactic to assert the film’s self-importance, which makes for an only episodically amusing experience. While The Lobster may have been meant to be perplexing, the film is hardly any more tolerable for it. As repetitive as the main theme’s music cues that endlessly punctuate the action, it bludgeons its point with the skill of a hardened bureaucrat. Obnoxious social norms can, and perhaps should, be attacked, but is it really true that you can only fight fire with fire?

Release date: March 25, 2016

Directed by: Yorgos Lanthimos

Starring: Colin Farrell, John C. Reilly, Ben Whishaw, Rachel Weisz

Stars: 3