It may not be pleasant but it’s important to get your cervix scraped on the regular

Happy women’s day! In celebration, here is an article about an important, but feared topic: vaginal health. Two great ways to treat your yoni right are regular pelvic exams and the Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine.

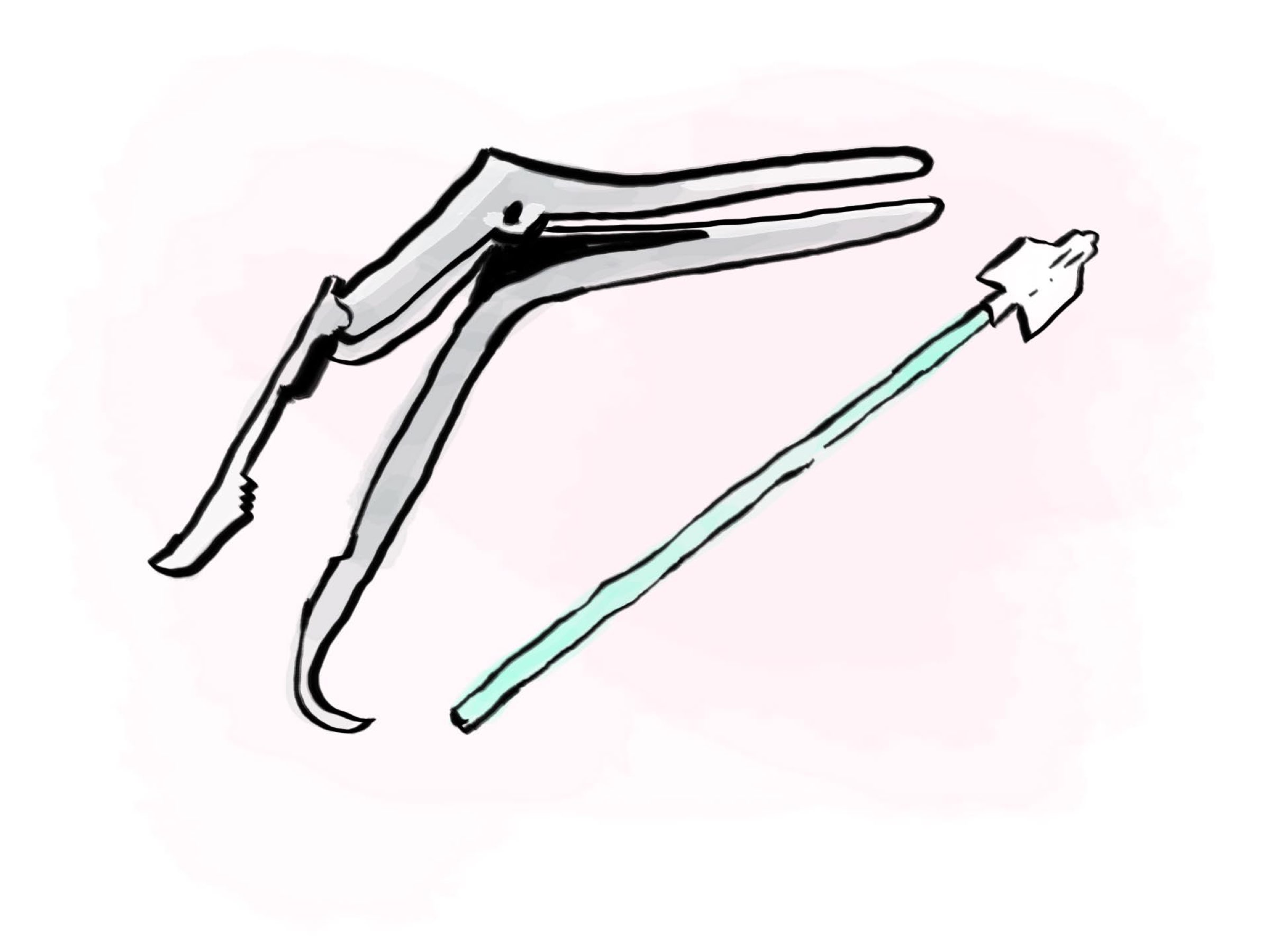

Pelvic exams are the only thing more dreaded than calculus exams. They’re uncomfortable, to be sure, but the mild and momentary discomfort is worth the reward of a muffin in fighting shape. The best thing you can do for your vagina is to have regular pelvic exams. A pelvic exam has three parts: a digital exam to check if your organs are healthy, a pap test to check for abnormal (pre-cancerous) cells and a check for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), if requested. The entire exam is over in 15 minutes if you take advantage of the pap-only clinics offered by Concordia University Health Services.

Although students are welcome to have their pelvic exam done as part of a full check-up, Health Services also offers pap-only clinics as an extra incentive to give your Garden of Eden the attention it deserves. These clinics are designed to leave students with few excuses to avoid this essential check-up. One great reason to take advantage of this service is that a visit to the pap-only clinic guarantees seeing a female physician. Also, the physicians taking part in the pap-only clinics specialize in female reproductive health—which translates to the most efficient and comfortable exam possible.

I would be remiss not to mention that HPV while writing about vaginal health. Gabriella Szabo, health promotion specialist and nurse at Concordia’s Health Services, explained that HPV is highly contagious—in fact, 70 per cent of people will experience an infection in their lifetime. The majority of infections are asymptomatic and a healthy immune system takes care of them in a couple of years. However, some infections can produce genital warts and abnormal cells on the cervix, which can lead to cervical cancer.

“Condoms can always decrease your risk of getting an STI (including HPV), but HPV can still be transmitted by parts of the genitals not covered by the condom,” said Josée Lavoie, a registered nurse at Concordia University Health Services. She recommends the HPV vaccine as the best protection. The HPV vaccine protects against the four strains of HPV that together cause 70 per cent of cervical cancers and 90 per cent of all genital warts.

While both of these conditions are highly treatable, the emotional trauma associated with diagnosis is a factor worth considering. “Getting a sexually transmitted infection is not just about getting the infection,” said Szabo. “Getting that diagnosis, it causes a lot of suffering. It’s very scary and people ascribe a lot of meaning to that. It causes a lot of distress. So getting the vaccination is an important part of helping to prevent that really negative emotional roller coaster that a person can experience with that diagnosis.”

To be sure, the stress of being diagnosed with an STI is the last thing a student needs in between presentations, papers, midterms and finals.

If the HPV vaccine is something you’re considering, the best time to do it is as a Concordia student. The university’s Health Centre charges only the cost of the vaccine, so it’s less expensive than at other clinics. Also, the health insurance offered by the Concordia Student Union (CSU) to undergraduate students covers up to 80 per cent of the cost of vaccination.

Our vaginas are something we don’t talk about enough, despite being literally the cradle of life. Whether your pink macaroon is filled with dreams, cobwebs or self-loathing, it deserves some quality attention.

Here are some questions you might be too shy to ask:

- Who should be getting a pelvic exam?

Any vagina owner who is sexually active or over the age of 21. Depending on your risk factors (which your health care specialist will assess), an exam is usually recommended every three years.

- Is there a rectal exam?

No! A rectal exam is not part of a regular pelvic exam for women.

- How can I work up the courage to show a stranger my vagina?

This particular stranger specializes in vaginas and has seen every permutation of genitals you can imagine. The reality is that your vagina is probably wholly unremarkable (to a physician).

- Should I “tidy up” for a pelvic exam?

It’s not necessary to coif your crumpet—your health is the first and only thing on a physician’s mind.

- I’m not sexually active/I always use condoms/I am monogamous, should I still go for a pelvic exam?

Absolutely! Many people associate pelvic exams with getting checked out for STIs. A pelvic exam also checks for abnormal cells on the cervix. If caught early, the condition can be monitored and treated. If left to linger unmonitored, abnormal cells on the cervix can progress to cancer.

So ladies, take care of your special flowers and they’ll take care of you.