Nadia Myre contributes her work to Woman. Artist. Indigenous. at the MMFA

Influential Indigenous artist Nadia Myre’s latest exhibition at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA) is part of Woman. Artist. Indigenous., “a season at the museum devoted to female Indigenous artists,” according to the museum’s website.

Titled Tout Ce Qui Reste – Scattered Remains, the exhibition is a retrospective of the artist’s work, combining five of Myre’s series created since the turn of the millennium: Indian Act, Grandmother’s Circle, Oraison/Orison, Code Switching and Meditation (Respite). This selection of artworks, along with the rest of Myre’s body of work, focuses on the retelling of Indigenous history and uses traditional Indigenous art practices and found objects to challenge Western colonial narratives.

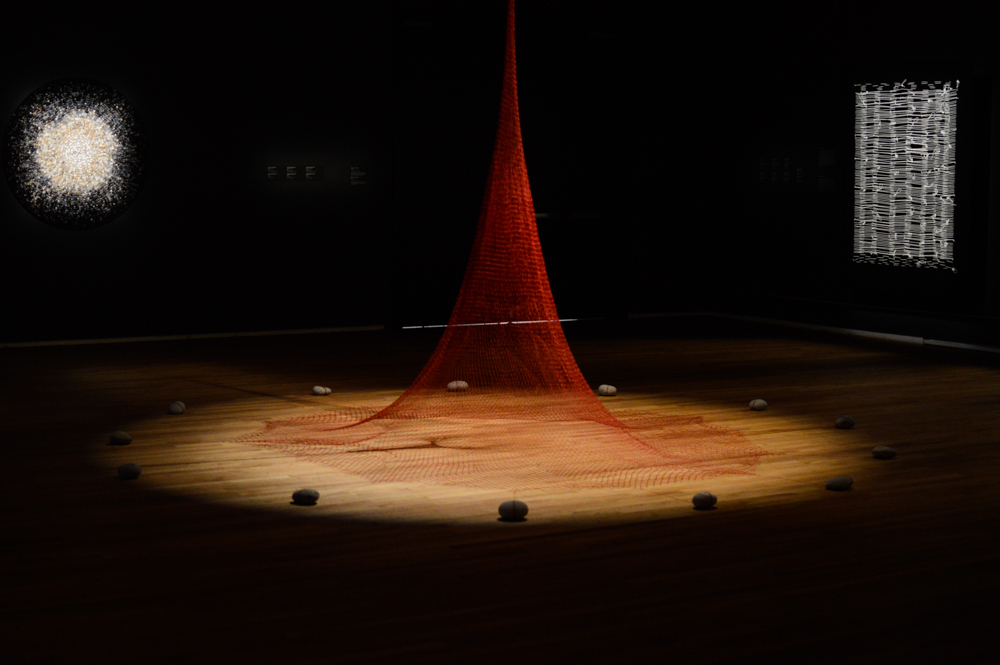

After reading the curatorial statement outside of the exhibition, viewers walk through the doorway and enter a large, dark, rectangular room. In this space, Myre’s series are nicely moulded together, with two- and three-dimensional artworks covering both the walls and floor of the room. The black walls and low lighting allow for backlighting and the white of the artworks to have an illuminating presence in the dark space.

The longer, perpendicular walls of the room are filled with large white-on-black photographic and textile pieces from Oraison/Orison (2014) and Code Switching (2017). The shorter wall to the left of the entrance features a looping video artwork as well as multiple images from Meditation (Respite) (2017). Across from this are more images from this series, works from the Indian Act (2000-2002) series and hanging sculptural pieces from Code Switching. The large installation works from Oraison/Orison and Grandmother’s Circle (2002) are spread out on the floor.

The curatorial presentation of the dark room and backlit artworks is both visually striking and thematically relevant, symbolizing what Myre intends to do in her work—repurpose Indigenous cultural objects to create light in a dark history.

The Indian Act artworks are perhaps the most explicit reference to Indigenous politics in the exhibition. Created with the help of many fellow Indigenous artists, this series of framed textile works takes on the challenge of covering up all 56 pages of the Indian Act using red and white glass beading. Myre’s piece draws attention to the legal rights of First Nations people in Canada, which are so often written over and ignored.

Grandmother’s Circle is a visual depiction of the artist’s attempt to trace her heritage. She unfortunately discovered very little about her Algonquin side, due to her mother being placed in an orphanage. In this work, large wooden poles are tied and placed together to create structures in the shape of wishbones. The MMFA’s website describes them as “a barrier that symbolizes the access to ancestral wisdom that was denied to Indigenous peoples,” similar to the residential school system.

The Oraison/Orison series, made up of both print and installation works, explores the permanence of memory and the impact life events can have on our bodies. A large kinetic installation piece, made of a red fishing net, moves up and down, mimicking the action of breathing. An oversized woven basket filled with tobacco—often used in First Nations ceremonies—wafts a subtle smell throughout the gallery space. A series of prints depict the white thread stitching on the back of the Indian Act artworks, and are reminiscent of scars on one’s skin.

Circular prints from Myre’s Meditation (Respite) series depict several close-up photographs of traditional meditative beadwork. These beaded designs are inspired by Indigenous spirituality and images of the cosmos, and explore the neverending properties of the universe.

Myre’s latest series, Code Switching, was produced during an artist residency sponsored by the MMFA. The artworks in this series are made of the collected fragments of European settlers’ pipes, which were historically used along with tobacco as currency with Indigenous populations. According to the museum’s website, Myre reclaims these fragments and repurposes them, using traditional beading techniques as a way of “sparking reflection and building bridges between cultures.”

Tout Ce Qui Reste – Scattered Remains will be on display at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts until May 27. It is located in the museum’s Discovery Exhibitions section, which is free to visit for people under the age of 31. For those over 31, entry is $15 or free on the last Sunday of every month.

Feature photo by Mackenzie Lad.