Marc Ellison is an award-winning photojournalist based in Vancouver. He sat down with The Concordian to discuss his experiences as a photojournalist in foreign territory with highlights from his time in Uganda.

How did you first get involved in journalism?

It was a very roundabout path. For 10 years I was actually a computer programmer. I quickly realized that being in a cubicle wasn’t really what I wanted to do. I love to travel. I love photography. I love writing. It was only after spending some time in Rwanda in 2007, living with Rwandans and talking to Rwandans about the genocide, that I realized storytelling is what I wanted to do. After that experience in Rwanda I basically came back to Canada and put in my applications for journalism school.

What are some of the factors that made you decide to work in developing countries rather than in Canada?

We’re in a time where foreign bureaus across the world are closing and I don’t think enough journalists do go abroad. I also think there are many countries that are underreported and often misreported as well. You know we talk about Uganda with child soldiers where if you were to believe Kony 2012 you would think the war is still going on. People would have you believe people are concerned about capturing Joseph Kony but really the women I interviewed out there are more interested in putting bread on the table. They don’t care about Joseph Kony. Those are things I think are important to cover. I think Africa as a continent doesn’t get the same amount of airtime as the Middle East. I was in South Sudan last year and there was a huge refugee crisis that unravelled at the same time as Syria and yet it barely hit the airwaves here in Canada.

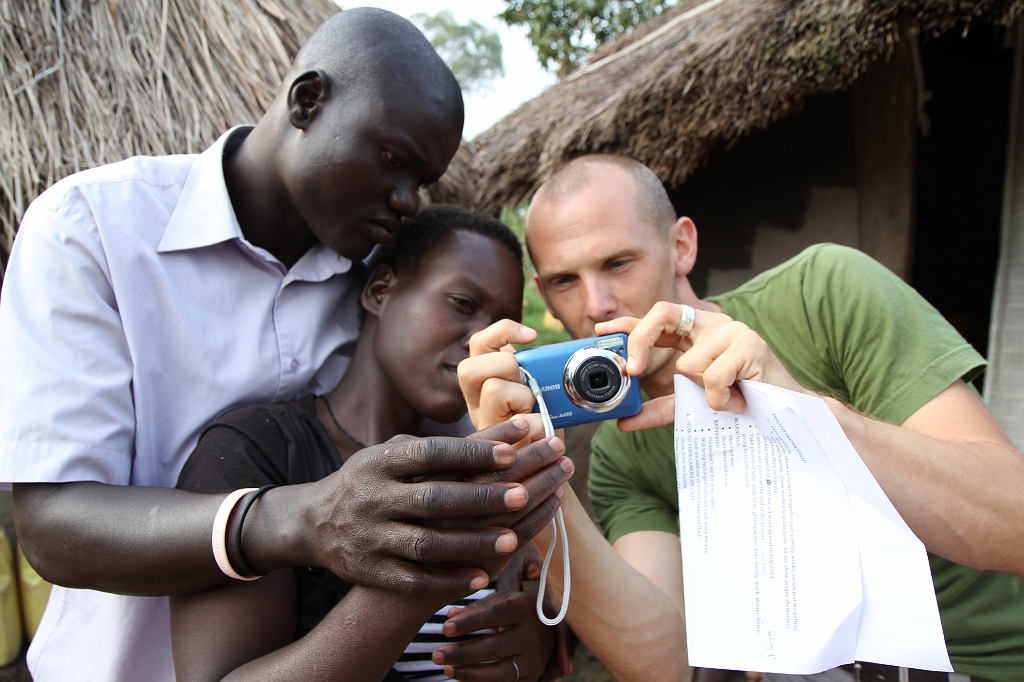

When you were working with former women child soldiers in Uganda, you let them take their own photographs. What are some of the benefits of participatory photography?

For a start you can frame a photo to depict what you want to show. For example South African photojournalist Kevin Carter took a photograph of a child with a vulture flying overhead. What you don’t see in that photo is that the child is very close to an UNHCR (United Nations High Commission for Refugees) tent. So it’s very easy as a photojournalist to show what you want to show. With giving the women cameras you’re not only allowing them to tell their own stories but there’s no trickery there. They are showing you what they want you to see. You’re getting this fly-on-the-wall, unadulterated view of what their lives are like. It doesn’t dress it up. It shows you what their lives are really like.

How do you ensure the dignity of people you are photographing?

In the Uganda project I don’t really want to try and sensationalize the issue and I don’t want to take advantage of the women. It’s interesting that the one photo that is arguably sensationalist is the one with the woman showing the scars on her chest. I always have to point out to people that that photo wasn’t actually my idea. The woman was talking about being stabbed in the chest with a bayonet. She said to the translator, “I want people to see this to understand that as a result of this injury I can’t work.” That really is the exception to the photos I’ve taken. I really don’t want to take advantage of these women, but I want to portray them how they would like to be seen. You can see on my website there’s a lot of very tasteful portraits of them either working with their family or in the market or things like that. I do my best. If somebody takes a photo of you, you want it to not necessarily be flattering but truthful.

Where do you think the market lies for less sensational photography?

Sadly there is the saying in journalism: if it bleeds it leads. It’s basically the same with photography. For the most part the more sensational types of photography are going to be what sells. It’s unfortunate but it’s just the way of the world.

To learn more about Marc’s work visit marcellison.com

To see more of his work in Uganda visit dwogpaco.com.

All photographs by Marc Ellison.

[nggallery id=22]