How she fought against the transphobic Rule Number 9

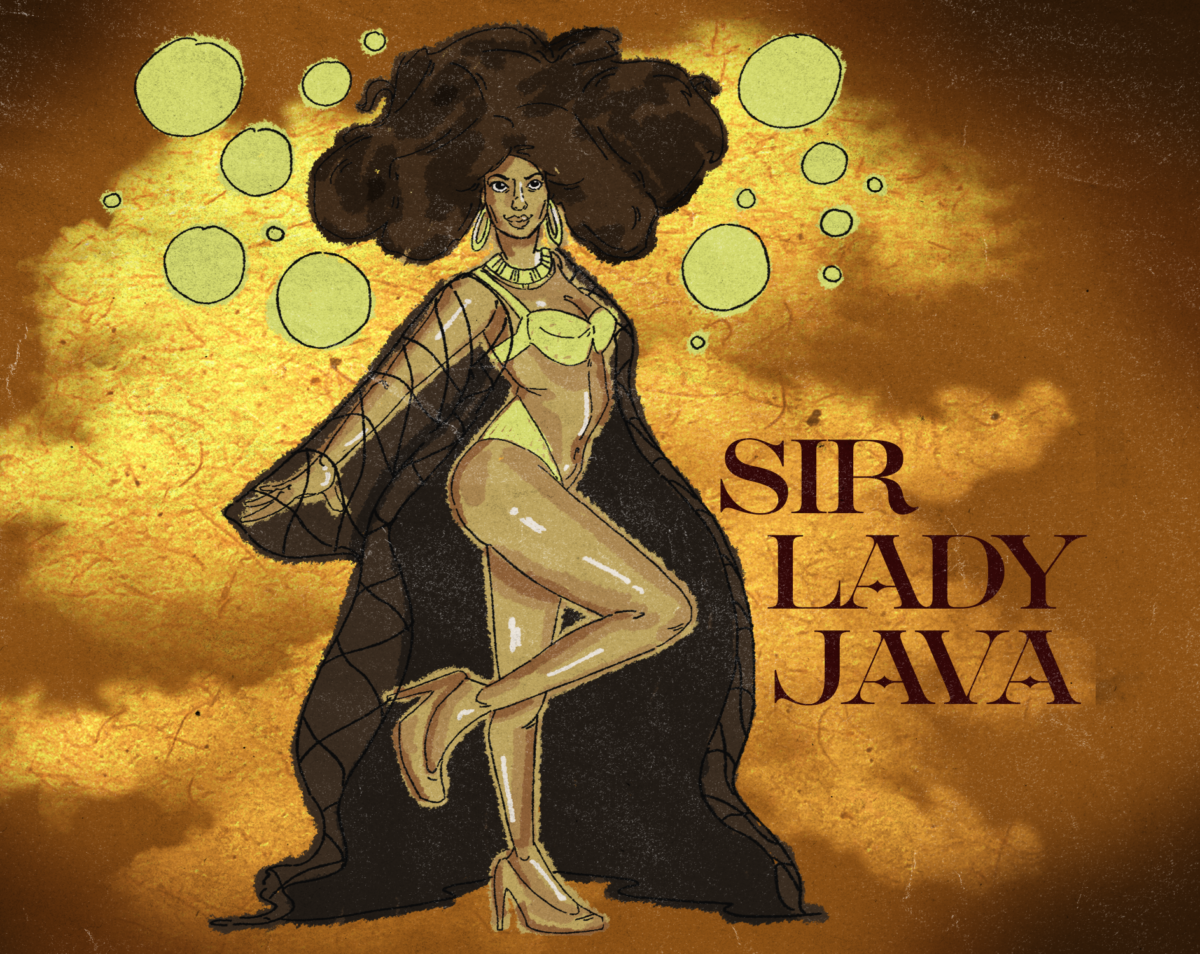

Sir Lady Java is an American transgender rights activist and performer. She performed in the Los Angeles area from the mid-1960s to 1970s.

Java was born in New Orleans, Louisiana in 1943 and transitioned at a young age with the support of her mother.

After singing and dancing in local clubs, she moved to Los Angeles to further her career and by 1965, performed in a nightclub owned by Comedian Redd Foxx that welcomed other great entertainers of the time like Sammy Davis Jr., Richard Pryor, Flip Wilson, Rudy Ray Moore, LaWanda Page, and Don Rickles.

In September 1967, the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) ordered Redd Foxx’s club to cancel Java’s performances, but they didn’t comply. The LAPD then threatened to fine the club and arrest Foxx if they continued hosting her, using a city ordinance against cross-dressing.

Before today’s war on drag shows and the fight to ban them, there existed laws like Rule Number 9. The city ordinance in Los Angeles, California, stated, “No entertainment shall be conducted in which any performer impersonates by means of costume or dress a person of the opposite sex, unless by special permit issued by the Board of Police Commissioners.”

As part of the rule, performers had to wear a minimum of three “properly gendered” items on them.

Even though any form of public gender nonconformity had been outlawed in Los Angeles since 1898, the Board of Police Commissioners developed Rule Number 9 in 1940 to require bar owners to get special permission to host entertainment which included any sort of cross-dressing.

As a response to LAPD’s crackdown, Foxx’s club applied for a permit to host Lady Java in October 1967, but was refused.

On October 21, Java protested against the rule by picketing in front of Foxx’s club advocating for her right to work. With the help of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), she challenged Rule Number 9 as unconstitutional in court.

The court rejected her case, stating only club or bar owners could sue the police department. Java and the ACLU could not find any owner willing to join them in their fight.

In 1969, Rule Number 9 was ultimately struck down by the California Supreme Court in a separate case. Although Java’s case was not the one to dissipate the transphobic rule, she is recognized as a trailblazer for transgender performers and drag queens.

As stated on the ACLU’s website, police at the time were not just cracking down on a couple of drag queens — their fight against “deviant” activities actually targeted the whole LGBTQ+ community.

“They were attacking drag performers in order to target bars and clubs that often served as the only public places where gays and lesbians could gather. The police made no real distinction between gay people and transgender folks,” reads the website.

With today’s political climate in the US directly targeting the drag community, it is important to remember Lady Java’s activism and fight against Rule Number 9.