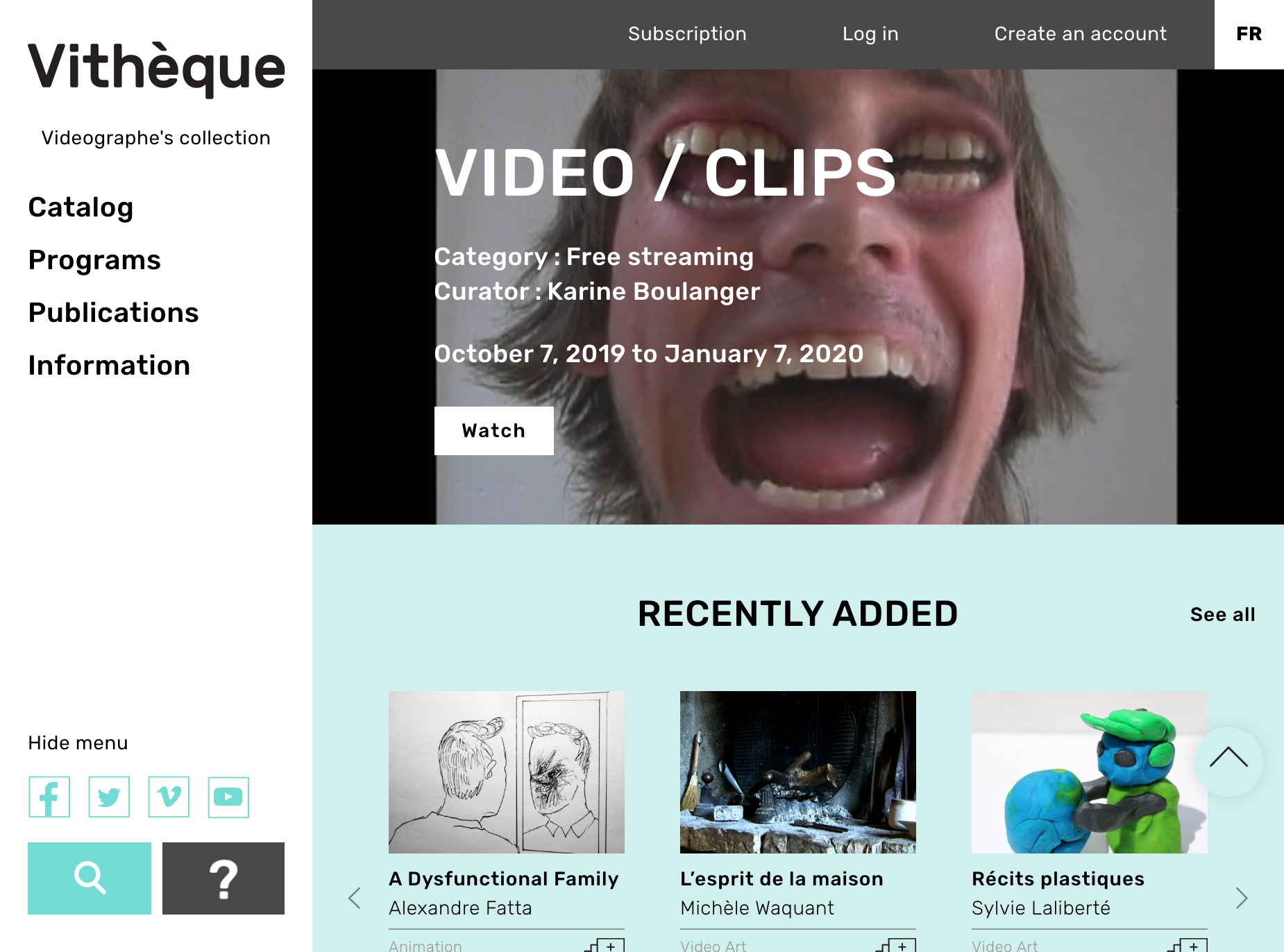

Vithèque, a self-proclaimed digital anti-giant, offers access to more than 2,000 titles

Since Spring of 2019, the online streaming service Vithèque has been available to students of the Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema through the school’s library website. The new platform is now on a campaign to encourage Concordia students to use it. They have been touring the university’s classes and advertising their services all November.

Vithèque has been serving as the online streaming platform of Vidéographe since 2017. It is a film production and distribution company that was founded as a division of the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) in 1971. Two years later, Vidéographe became independent of the NFB, and has been growing ever since. While they don’t directly produce as much content themselves nowadays, they still help Quebec artists push the boundaries of experimental filmmaking and video art. They offer workshops, residency programs, bursaries, equipment and more.

Their work encompasses animation, multimedia art, video essays, documentary, dance videos and some fiction. Their new platform, Vithèque, brings together their entire archive, and makes it available to their subscribers.

“We’re a good alternative to mainstream streaming services such as Netflix, because not only is our offer more interesting if you’re looking for more specific auteur films, […] Vithèque also pays the artists better,” said Karine Boisvert, who put together the platform for Vidéographe.

She added that 50 per cent of the platform’s revenues go directly to the content creators. Vithèque and Vidéographe function like NGOs; their main goal is to give back to the community of artists they work with. The other half of the revenue helps to keep the platform functioning, extending their public and funding additional services for artists.

“It’s the subscribers and agreements with schools and libraries which allow us to keep expanding,” said Boisvert. “Since the beginning, Concordia seemed like an important collaborator for us, along with UQAM, because of its large film program and interest in experimental filmmaking.”

Pierre Falardeau, Robert Morin, Anne Émond, Pierre Hébert and Sylvie Laliberté are among the most well-known artists to have their work available on Vithèque. The platform’s website claims it hosts films “documenting key events in contemporary Quebec, such as the workers movement, the October crisis, the feminist movement, counterculture and LGBTQ2+ affirmation.”

Some video installations which Montrealers might have seen in a gallery or museum could also very much be found on Vithèque. For example, Chloë Lum and Yannick Desranleau’s What Do Stones Smell Like in the Forest, which was displayed at the Montreal Museum of Contemporary Art (MAC) this summer, is also available on the website.

Vidéographe adds about 30 new titles to its collection every year. Whether it be to deepen their research or just to explore Quebec experimental film history, at home, on a rainy Sunday afternoon, Concordia students now have access to an even wider array of possibilities.

For more details, visit https://vitheque-com.lib-ezproxy.concordia.ca/en/home.