Modern romantic comedy movies have made me lose all hope for the genre—but were rom-coms ever that good in the first place?

I have been trying to write this article, but I got distracted rewatching You’ve Got Mail for the hundredth time. You see, romantic comedies have always been my guilty pleasure—with all the corny meet-cutes, the “Will she, won’t she?”, the slow burns and all the tropes, and the inevitable confession of love. Scenes from my all-time favourites live rent free in my mind, and I have long wished to be Meg Ryan, the It-Girl of rom-coms in her time.

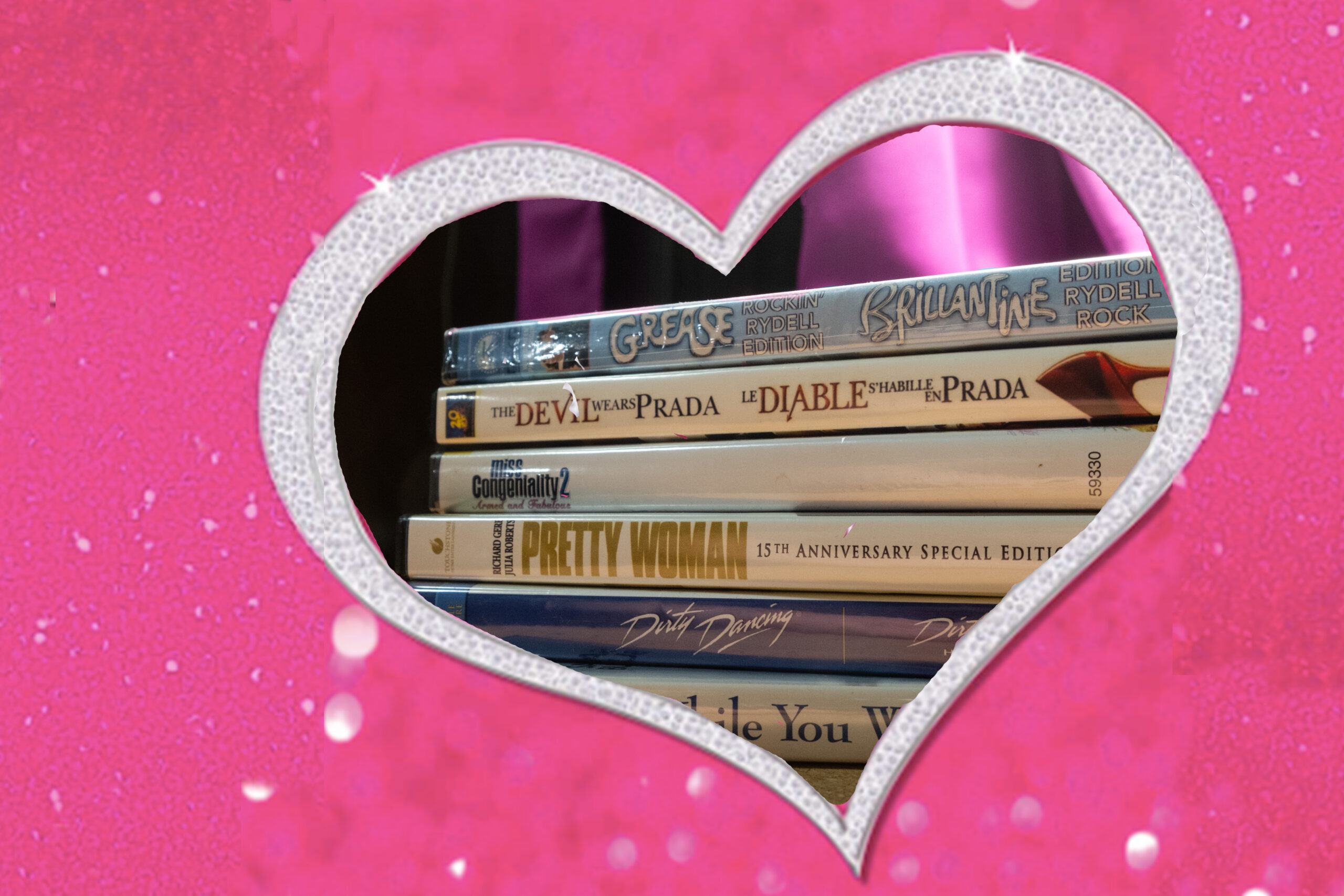

This movie genre was a major player in the ‘90s movie-scape, with movies like When Harry Met Sally, Notting Hill, 10 Things I Hate About You, and Pretty Woman smashing box offices and providing a decent dose of fluffy escapism. But since then, something seems to have shifted. Modern rom-coms often come off as unmistakably cheap, featuring little personality and an abundance of cringe-worthy dialogue.

Because of my love for love-based media and my quest for a modern rom-com that’s as satisfying as the classics, I was beyond excited to see Anyone but You, the new rom-com starring Sydney Sweeney and Glen Powell. I had been told that this movie was an exception to the phenomenon of disappointing rom-coms. Well, I was lied to.

Bad writing, bad acting, bad movie. Was this written by ChatGPT? I wondered many times. We laughed at the movie far more times than with it, and certain moments had me rolling my eyes so far into the back of my head that I’m sure they’re still stuck there. Anyone But You just proved what I’ve been saying—modern rom-coms suck, and the golden age of the genre is over.

However, this thought led me to a second one: Were rom-coms ever so golden in the first place?

The closer you look, the more you realize these so-called classic movies were rife with issues. It’s hard to avoid the glaring fact that they all pretty much revolve around thin heterosexual white people. They’re often sexist, play into hetero-normative gender roles, completely wonky on the issue of consent, and feature tokenization or just downright offensive portrayals of minority groups.

So-called romantic elements, too, can leave viewers scratching their heads. Remember that scene in The Notebook where Noah dangles from the ferris wheel until Allie agrees to go out with him? Super romantic! Male leads are often alarmingly pushy, and rewarded for this behaviour.

Not even my favourites have aged well. What’s the message of You’ve Got Mail, for example? The big CEO shuts down Kathleen Kelly’s family-owned bookstore, effectively destroying her dreams…and it’s ok because they live happily ever after?

So, where’s the middle ground? Where are all the well-written, beautifully-made movies that are actually politically progressive and reflect a more open understanding of what love can look like?

Now is a better time than ever to revitalize the genre. I propose a formula that takes the best elements of classic rom-coms and combines those with a modern lens.

So bring back rom-coms. But not like this. And maybe not like that, either.