The government’s plan to cancel 18,000 immigration files is irresponsible

Picture a family of four. The mother is an accomplished university professor, currently finishing her PhD in management and marketing in partnership with various French universities, despite being based elsewhere. Her husband, a qualified software engineer, works for the country’s biggest public company. Their two sons, aged six and 10, are not only healthy, but very sweet and incredibly smart. Like their parents, they both can speak three languages fluently—including French—and the older of the two is currently learning his fourth.

This picture-perfect family happens to be my cousin’s. She lives in Algeria, where yes, her situation is pretty good as of now—but unstable socio-economic conditions in the country and the rise of various militant groups pushed her and her husband to apply for immigration to Canada back in 2012. They are now onto their second attempt, but the CAQ government’s Bill 9 might get in the way of their Canadian dream.

On Feb. 7, the Quebec government announced that in order to pass its upcoming immigration bill, commonly referred to as Bill 9, it would proceed to cancel all 18,000 Skilled Worker Program applications currently pending for treatment and approval by the province’s Ministry of Immigration, Diversity and Inclusion (MIDI), according to Le Devoir. The announcement was made nearly 10 days after Premier François Legault promised those files would be duly taken care of before his party would submit its new immigration bill.

Simply put, this measure is irresponsible and thoroughly unfair. Handling those 18,000 documents is part of the government’s duty towards its applicants, and cancelling them in order to promptly pass a more restrictive immigration law can only be seen as a way for the province to wash its hands from the expectations it ought to meet, while jeopardizing the future of thousands of people.

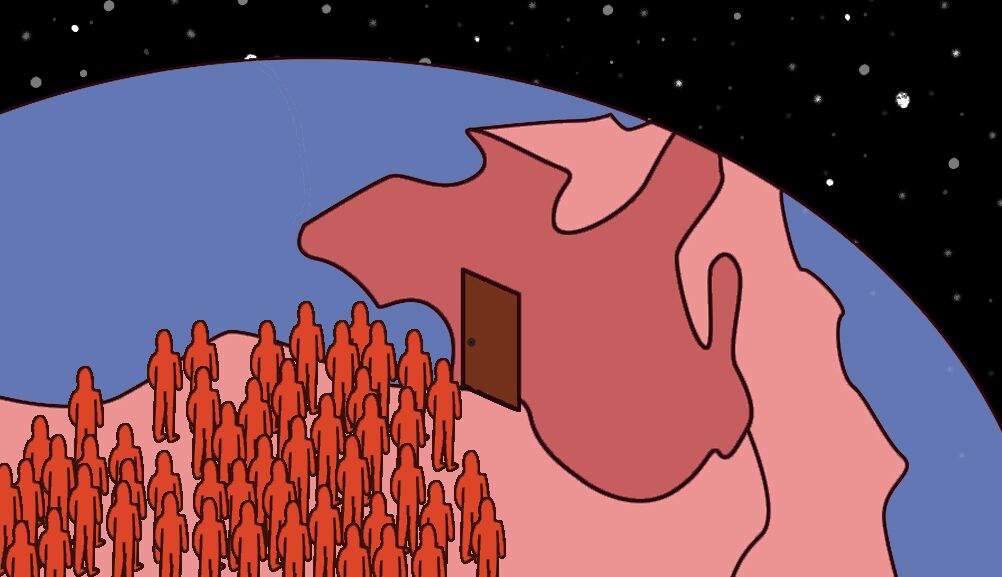

Think about it: behind those 18,000 immigration requests are actual people, spread across the globe, hoping for a better future here in Quebec. Those 18,000 files affect the lives of men, women, children; entire families, or hopeful young adults. In total, these files represent about 50,000 people, as each file represents a family, according to Le Devoir. Some of them—like my cousin and her family—have been waiting for years, hoping not even for an acceptance, but merely a response from our government. According to the CBC, some applications date back to 2005, totaling a wait time of 14 years.

There’s also a lot of money going into this: applying for immigration to Quebec costs around $1,000, which would correspond, in total, to $19 million to reimburse all those applicants—which Immigration Minister Simon Jolin-Barrette promised to do, while also suggesting that applicants re-apply once the new bill has passed, according to Le Devoir and Global News.

This isn’t a small amount; $19 million could be used to take care of much more pressing, important issues. Besides, asking people to simply “re-apply” goes to show that Minister Jolin-Barrette has no idea the burden that immigration bureaucracy entails, and just how much it impacts the lives of the people applying.

However, the issue doesn’t end there. The new proposed bill on immigration, while also reducing the number of immigrants admitted in the province, puts a stronger emphasis on “learning French and learning about democratic values and the Québec values”, as the Bill reads. This resonates with François Legault’s electoral promise to establish a French and “Quebec values” test for immigrants to pass after three years in the province, according to The Globe and Mail. While a French test might be, to a certain extent, understandable in order to maintain the French-speaking character of the province, a test on “Quebec values” can only be seen as xenophobic.

One of our province’s strengths is its welcoming environment and its diversity. Setting up such a restrictive examination would weaken such strengths, while also clearly discriminating against immigrants. Surely all the people born and raised here have some core values they might not agree upon, but those people would never be tested on them the way immigrants would be.

I am not the only one contesting this measure. All three of the main opposition parties of the National Assembly have also expressed their disagreement, according to Le Devoir. Meanwhile, the Quebec Immigration Lawyers Association (AQAADI) are also hoping to take this to court, according to the same source.

Our government needs to reconsider its approach to immigration issues, starting with the cancellation of pending immigration requests. The CAQ owes it to the 50,000 applicants it’s letting down, to the current immigrants of Quebec that are only working to better our province like any other citizen, and to the rest of its society.

I can’t help but think of my cousin. She’s brilliant, speaks French fluently, and she and her family have the potential to bring so much to our province. She deserves better from our government.

Graphic by @spooky_soda