Cree artist Kent Monkman and his long-time collaborator Gisèle Gordon discussed the process behind their recent book project recollecting the memoirs of Monkman’s time-traveling, supernatural and gender-fluid alter ego.

On Nov. 20 at the Grande Bibliothèque de BAnQ, an audience of primarily Concordia students and alumni were treated to a rare performance by Miss Chief Eagle Testickle herself. Donning a glittering transparent robe and sharp stiletto heels, Miss Chief orated an excerpt from her fantastical memoir, beginning with her eye-witness account of the creation of the universe when she was only a young elemental being.

This was followed by her recounting of her turbulent yet thrilling descent to earth, her erotic discovery of her new human body, and her horror at the brutal and neglectful treatment of the sacred belongings of the Indigenous people of Turtle Island (aka North America) she had come to know and love.

Artist Monkman and writer Gordan’s new book weaves the origin story of Miss Chief into the intertwining histories of the Cree people and the colonization of Canada. True stories of real historical figures are told through the perspective of the imaginary protagonist—a familiar intervention to those already well-versed in Monkman’s prolific painting career.

Miss Chief has long been a staple in Monkman’s body of work that seeks to challenge canonical representations of North America in the history paintings of 19th-century artists such as George Catlin and Paul Kane. Miss Chief interrupts the reductive colonial gaze through asserting a queer Indigenous subjectivity into Monkman’s historical scenes.

Monkman and Gordan’s approach to writing Miss Chief’s memoir was largely informed by both of their backgrounds in performance art and film, and the text certainly lends itself to live oration. Listening to Miss Chief verbally recount anecdotal encounters filled with tension and rich, witty dialogue brought Monkman’s paintings to life and tied them all together into a fully developed narrative.

After Miss Chief’s performance, Monkman sat down with Gordan to discuss the inception of the book project and the enduring process of piecing it all together. The collaborators had spread out prints of all of Monkman’s dynamic paintings and began sorting them into chapters of what would constitute the story of his central character. Monkman remarked how “the memoir became an exercise in filling in the gaps of her story,” and that he hopes to continue developing the life cycle of Miss Chief in future endeavours—perhaps a project inspired by Peter Paul Rubens’ series on the life of Marie de’ Médici at the Louvre Museum.

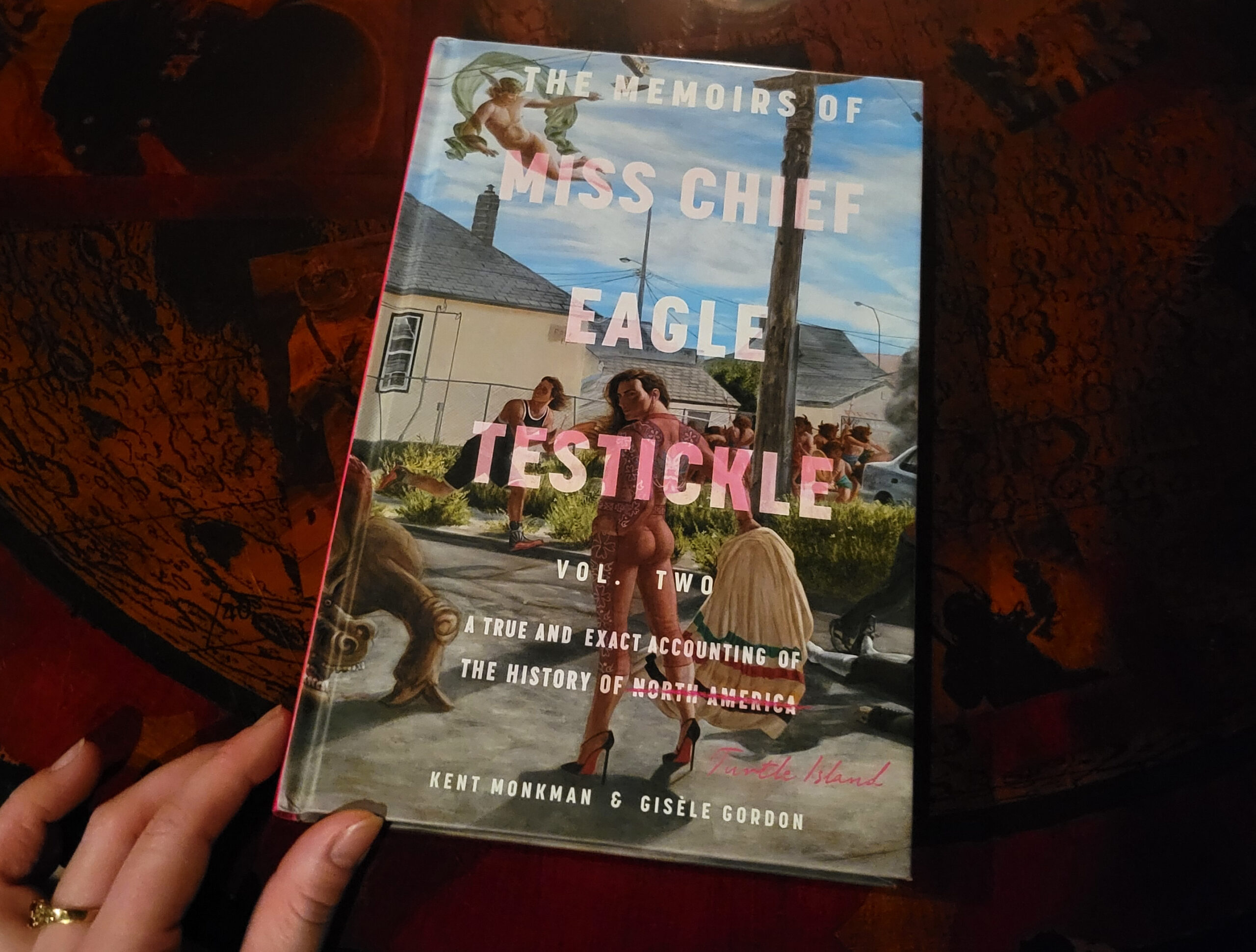

Volume two of The memoirs of Miss Chief Eagle Testickle: A true and exact accounting of the history of Turtle Island is now available in bookstores starting today, Nov. 28!