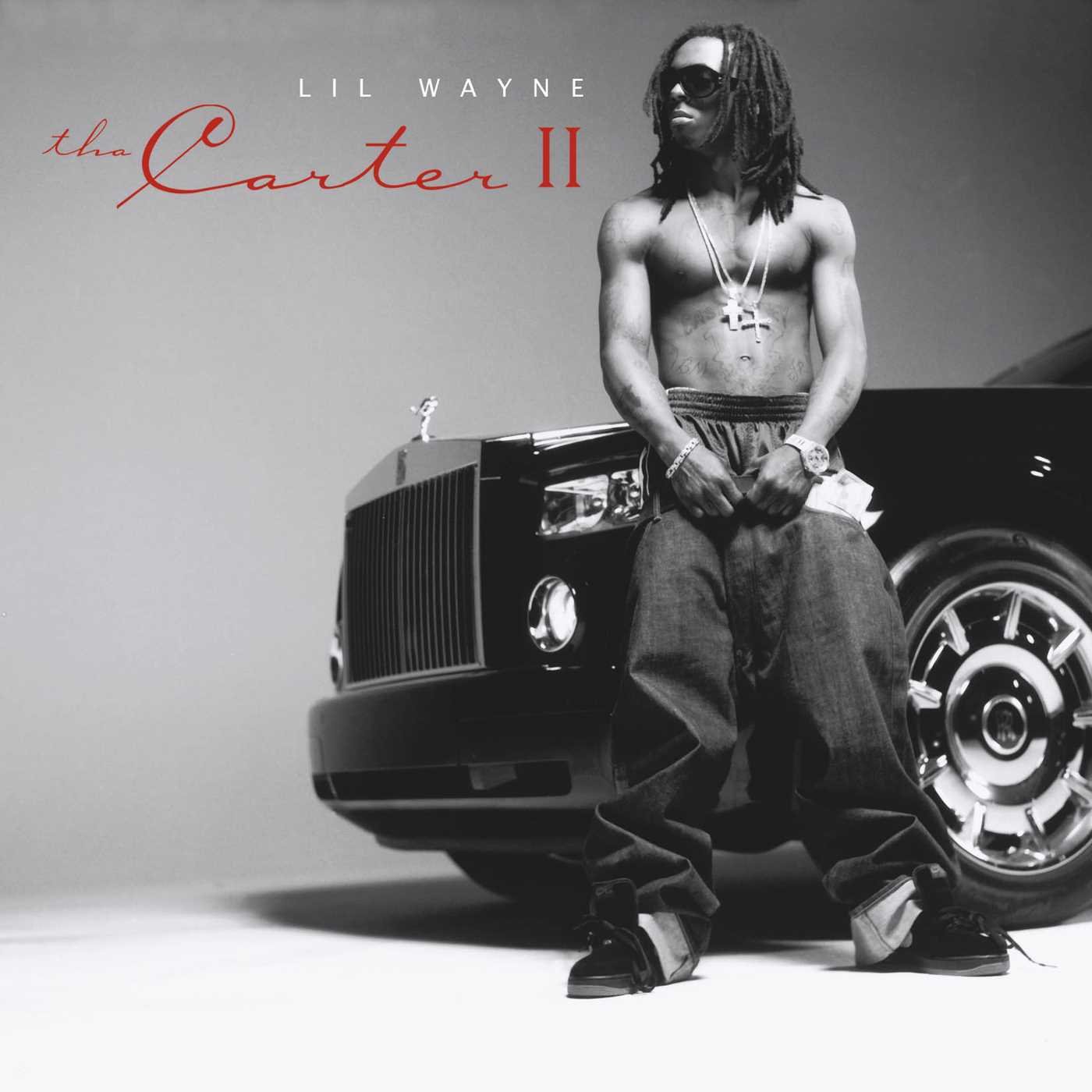

Taking a look back at the hip hop behemoth’s fifth studio album — his last before becoming a pop culture juggernaut — and his magnum opus.

The first time that I ever heard Lil Wayne was one of the most pivotal and life-changing moments I’ve ever experienced as a music fan, and I remember it vividly. It was late 2004, I was nine years old and Birdman’s “Neck of the Woods” music video was playing on BET. As it began, I had no idea who either artist was, but as soon as Wayne started rapping that opening verse, I was instantly hooked.

I spent the rest of that afternoon eagerly waiting for the video to play again. I was so intrigued by his raspy voice, his charismatic and dynamic flow, that his lyrics were echoing through my head, and I couldn’t wait to hear more. Fast forward almost a year, and my wish came true, as the video for “Fireman,” the first single off of his then-upcoming fifth studio album Tha Carter II had released.

Wayne displayed an energy that I had never seen a rapper have before that video and it was unmatched in my eyes. His extremely unique cadence and flow, as well as the abundance of swagger and confidence he exuded, made him incredibly captivating to watch. From that day forward, I knew whatever CD this song would end up on, whatever he did next, I needed to hear it.

When I finally got my hands on Tha Carter II soon after its Dec. 6, 2005 release date, it blew by every expectation I had for it and has remained one of my favourite albums of all-time ever since. The LP is a near 78-minute, 22 track masterpiece that sees Wayne exploring a multitude of sounds, proclaiming to be the “Best Rapper Alive,” and showcasing exactly why he deserves that title.

This was an era where both Jay-Z and Eminem were on hiatus, and Wayne’s label Cash Money Records had lost pretty much their entire roster of artists. Even if that was a detriment to the label, it served Wayne extremely well, as all of their resources were put behind him, and Wayne put the label on his back and carried them to a level of success they’d not yet seen.

From the outset, Wayne lets the listener know who he’s representing, proclaiming that it’s “Cash Money, Young Money, motherfuck the other side” on the album’s Heatmakerz-produced opener “Tha Mobb.” It’s an intro that sees the New Orleans rapper immediately going for the jugular, asserting his dominance as he aggressively tackles the thudding bass of the instrumental, establishing three things: he’s here, he’s hungry and he’s gunning for the top.

They say the pen is mightier than the sword, and in that case, Carter II-era Wayne’s pen could defeat Excalibur. Throughout this album, Wayne exercises every skill in his arsenal, knowing that he is the sharpest he’s ever been. Evolving past the simple, catchy raps that made early-era Cash Money albums popular, his writing is clever, it’s layered, and it’s perfectly delivered as he adapts his flow to any beat thrown his way.

The production on this album is significant for more than just its diversity though, as it’s the first Wayne album, both solo and as a part of the Hot Boys, that doesn’t have a single Mannie Fresh instrumental. This was a real departure from the sound fans had grown accustomed to and it could’ve easily affected the appeal of Wayne’s music at the time. Instead, he was able to deliver something that garnered him a level of acclaim and respect he hadn’t yet seen.

This is largely due to Wayne’s adaptability to this album’s sonic diversity, as he’s always on point, no matter what the instrumental backdrop of the track may be. His braggadocious tales of drug dealing are superbly scored by the triumphant trap instrumental of “Money on My Mind,” which remains one of the best songs he’s ever made. The crackling and soulful Isley Brothers sample on “Receipt” is perfectly complemented by his raspy yet buttery smooth delivery, as he showcases his softer, more romantic side.

Moments like the Kurupt-assisted “Lock And Load,” the bouncy “I’m a D-Boy,” and the dub-influenced “Mo Fire” also stand out as highlights, but nothing on this album is as perfect as “Hustler Muzik.” As far as Wayne’s singles go, not one of them holds a candle to it. The track is smooth and introspective and showcases the many facets of his personality: the boastful hip hop star, the young street veteran, and fatherless child, still affected by his dad’s absence. It’s the quintessential Lil Wayne song, potentially his best, and one of the best songs in the history of his genre. It’s that good.

The same can be said for Tha Carter II as a whole. It’s just that good. Its impact can’t be understated, and neither can the excellence of Wayne’s work on here. This album symbolized a turning point in Wayne’s career, both artistically and commercially. In taking risks musically and making an album devoid of any of the trappings of mainstream hip hop at the time, Wayne managed to both come completely into his own and became a superstar in the process.