girl in red was impressive from the moment she got settled on stage

The first time I experienced Marie Ulven – who goes by the artist name ‘girl in red’ – was in the early spring when she played at the Scandinavian showcase festival by:Larm, in Oslo. At her home field show, we were being introduced to a young and fairly confused girl serving us heartbreaking stories with the attitude of Joan Jett and the humour of Will Ferrell. I was excited to see how 2019 had formed the up-and-coming artist, and I must say that at the end of the night I was very pleased by her progress.

Ulven is 20 years old, and produces all of her charming lo-fi pop songs from her room. Her bedroom-pop reaches out to all of the misfits of the competitive generation Z, and tells us it’s okay to be more into girls than boys or vice versa, and that you are allowed to feel down or depressed, even though the sun is shining outside.

Thursday evening, Le Ministère on St-Laurent St. was completely packed with young fans with sparkling eyes and lots of excitement. As girl in red entered the stage, the crowd exploded in high pitched cries and shrieks from the female-dominated crowd.

The show opened with the latest released single “bad idea.” Even though people were ecstatic by her appearance, it was a bit of a wobbly start for Ulven and the band – an unbalanced sound level made it almost impossible to hear the detail-oriented production, especially because of the dominating lead vocals volume being way too high.

You could tell that Ulven was affected by the technical bothers, stuttering through the introduction. She told us she had a sore throat and couldn’t hear anything through her in-ear monitors. A lot of warning signs made it a bit hard for me to believe that she would be able to deliver as convincing of a performance as she had the first time I saw her.

Luckily, I was wrong.

Even though Ulven didn’t seem to be catching either her breath or foothold until the fourth song of the gig, “summer depression,” the crowd was positive and uplifting. Ulven and the band were finally past the sound difficulties, and they could finally open their eyes towards the big and warm Quebecois welcome that was facing them. This included both pick up-lines from the girls in the front rows, and a beautifully handmade fan art portrait.

Last but not least, the whole crowd singing “O Canada” at the top of their voices when Ulven complimented them for speaking French, which according to her is “the most sexy language ever.”

The national anthem really reached both Ulven and the audience, and hearts were being stolen from both sides of the stage.

The show reached new heights when “forget her” was flowing out of the speakers. Ulven was finally ready for takeoff.

We were already halfway through the show, but Ulven was relaxed and actually present with the packed venue. A lot of chit-chatting with the front row and storytelling came between absolutely banging and impressive versions of “we fell in love in october,” “watch you sleep,” and “girls.”

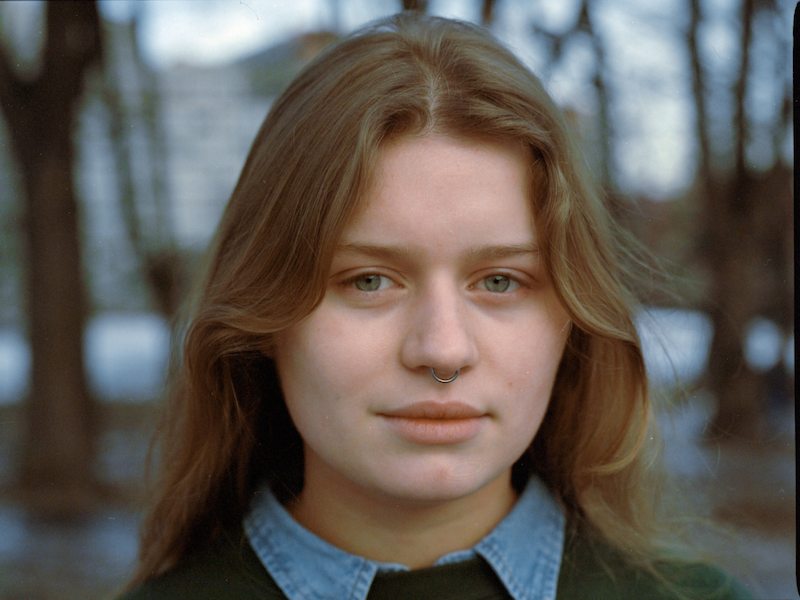

Finally, we got to see Ulven in her element. She demonstrated the perfect balance between being an absolute performer on stage, with her long hair surrounding her like a blond tornado, and a charming conferencier in the breaks, with blushed cheeks caused by the compliments and cheering from the “woo girl” crowd.

The show ended with a singalong of “say anything,” closed by the debut single “i wanna be your girlfriend,” when the band was playing in all their glory. All in all, girl in red was just as adorable and vulnerable as I remembered her; but this time, she was a little more hyped, although cold-infected, and professional. It took her a while to reach people’s hearts, but as she got comfortable and warmed up, she had all of us under her thumb.

Photo by Jonathan Vivaas Kise