Seen as an alternative or addition to the traditional red poppy, white poppies take remembrance one step further.

Every November, millions of Canadians wear the red poppy flower in the days leading up to Nov. 11 as a symbol of remembrance in respect for the veterans who died in the First World War. Sporting the poppy has been a practice in Commonwealth countries and the United States since the early 20th century.

It was originally inspired by the poem “In Flanders Fields” by John McCrae, a Canadian doctor and soldier who was inspired by the sight of poppies growing in a battlefield following his friend’s death. The donations that the Royal Canadian Legion raises through the distribution of poppies are used to support Canadian veterans and their families.

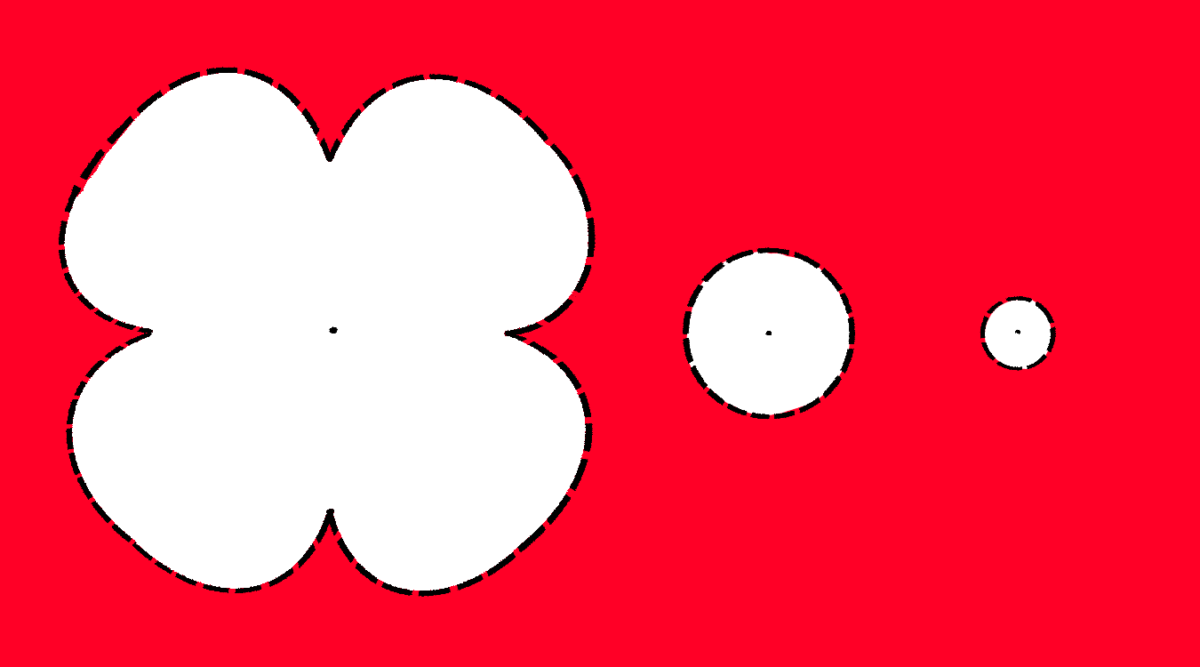

That’s the red poppy in a nutshell, but you may also have spotted white poppies this Remembrance Day. A symbol of remembrance for civilian casualties, the white poppy can be worn as an alternative or addition to the red poppy. Vancouver Peace Poppies describes the white poppy initiative as a means to end the normalization of war and the glorification of the military, and work towards a global message of peace. The goal is to delve deeper into the topic of war and consider the full effects it has on people, the environment, and society at large.

Despite its controversial nature, the white poppy is a welcomed addition for many. Personally, I appreciate that the white poppy aims to challenge the commonly-accepted discourse around war and inspires complex conversations.

The white poppy was first distributed by The Women’s Co-operative Guild in 1933. This United Kingdom-based pacifist organization was dedicated to working-class issues, and therefore had a vested interest in civilian affairs. Since they began promoting the white poppy, it has been especially popular in the UK, with thousands sporting the symbol.

Naturally, this practice has stirred controversy. Some consider the white poppy disrespectful and argue that the idea is reductive. It has raised questions surrounding the issue of copyright, seeing as the Royal Canadian Legion has trademarked the poppy symbol. In terms of ideology, it could be argued that the white poppy piggybacks on the red poppy, and that the original should be left alone.

The red poppy itself is often contested too, however. Robert Fisk, a British journalist and correspondent in the Middle East, argued in Independent that the red poppy has become a racist symbol as it only acknowledges Western soldiers and not the many casualties in foreign countries. I do agree that the culture of Remembrance Day can feel a bit absolute at times, with no room to discuss issues such as the one that Fisk presents.

While remembrance is important, and the sacrifice of veterans should be acknowledged, the conversation should not end there. We need to begin speaking more in depth about topics such as the military, causes of war, and conflict-resolution.

Next Remembrance Day, you may notice more white poppies. Maybe you’ll even choose to wear one.