The city’s game developers compose music that feels retro yet futuristic

Montreal has an abundance of video game developers who have created huge franchises, like Assassin’s Creed, and small, independent games, like The Shrouded Isle (2017) and SuperHyperCube (2016). The soundtracks of these games are outstanding, perfectly reflecting Montreal’s unique identity—vibrant and eclectic. The music ranges from cyberpunk synth to whimsical orchestration and retro-inspired beats.

Deus Ex: Human Revolution (2011), by Eidos Montreal, depicts a dark, neon-lit world polarized by augmented humans programed to wield special abilities. The game is set in the year 2027 in Detroit—home to a new technological boom—and the orange-tinted streets of Singapore. Michael McCann’s soundtrack further enriches the cyberpunk world of Deus Ex.

McCann balances high-octane tracks, like “Everybody Lies,” and moody, atmospheric pieces, like “Detroit City Ambient.” Tension is created during strategic combat sequences, which are amplified by the game’s clever use of music. Although the soundtrack takes inspiration from Vangelis’ Blade Runner (1982) soundtrack, as a lot of sci-fi media does, the world of Deus Ex is dramatically augmented by McCann’s stellar music.

Several years ago, French developer Ubisoft released a succession of experimental and artsy games, starting with Rayman Origins (2010). Out of that initiative, Ubisoft Montreal’s Child of Light (2014) was born. Hand-drawn, impressionistic art brought the game’s fantasy world to life. A palpable difference from the formulaic fare of other Ubisoft creations could be felt throughout the game, which was a decidedly new direction for the developers. It was a distinct change from the high-budget games Ubisoft is known for, like the Watch Dogs series. The soundtrack was no different.

Composer Cœur de pirate, a Montreal-based singer-songwriter, melded melody with whimsy, which can be heard on the track “Aurora’s Theme.” The song features lush cello instrumentation and a gorgeous piano sound. Unlike other Ubisoft games, Child of Light’s soundtrack is more subdued and has the ability to create transcendent moments for players.

Montreal indie developer Polytron released its hit game, Fez, in 2012. The game fell somewhere between retro and modern. The developers created a bright and colourful world, reminiscent of games made in the 90s. And yet, the game pushed the aesthetics and gameplay into territories that would never have been possible in that era. Navigating the world of Fez requires curiosity, a motivation to explore and the ability to think spatially in order to solve complex puzzles. Composer Disasterpeace also straddled the line between retro and classic.

The soundtrack was composed of familiar chiptune sounds—the crunchy electronic synths found in older games—but with a modern twist. For example, the track “Compass” fuses wavy electronic synths with a rhythm typically heard in classic games. “Majesty” features a chiptune melody combined with ambient synth pads and a drum machine—a sound so familiar yet so mystifying. The soundtrack felt inventive, yet it gave the game a warm sense of nostalgia.

Ubisoft Montreal’s Watch Dogs 2 is a game about hacking, dismantling big tech corporations and revealing the corruption of these conglomerates. The game is set in San Francisco, home to Silicon Valley and hundreds of startup tech businesses. A CTOS (Central operating system) controls the city and its inhabitants. The developers satirically portrayed the culture of Silicon Valley, skewering the pretensions of the corporate higher-ups. Despite how mediocre the game turned out, the soundtrack was phenomenal.

Composed by producer and DJ Hudson Mohawke, the music was influenced by contemporary electronic music. Mohawke used sampling, synths and a drum machine to produce a danceable and exciting soundtrack. “The Motherload” features distorted synth beats and an off-kilter drum sound, accompanied by a choir and handclaps. While the track “Cyber Driver” could have been a Run the Jewels beat, it harnesses a lovely synth sound that reminds me of the opening Playstation tune. This is one case where the music is definitely superior to the game.

Music is an essential part of the way people experience games. The more inventive composers get, the more memorable the soundtrack becomes. The aforementioned games took on a unique approach to music, showcasing the ways sound can affect the whole vibe of a game. And each of them exemplified the spirit of Montreal—a city caught between two cultures, a city of awe-inspiring art and architecture and a city that integrates old and new.

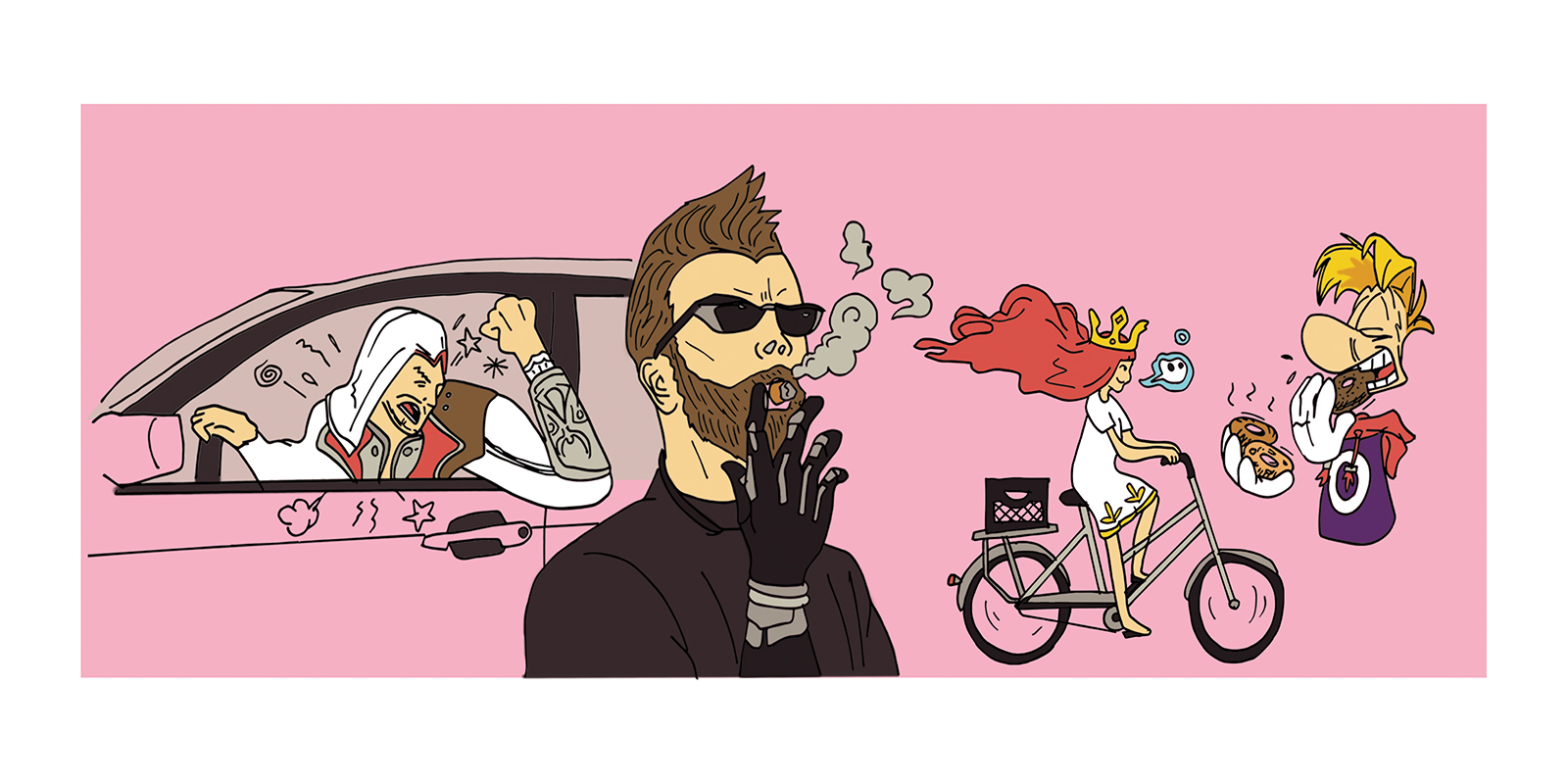

Graphic by Zeze Le Lin