TikTok’s newest music meme does more harm than good

Picture it: you’re at a house show (pre-pandemic obviously), you get approached by a ghostly guy in Dickies and Vans sneakers, boasting a small rolled-up beanie with a cigarette behind his ear. He introduces himself and then leans in to sarcastically ask you if you know the band that’s playing, because they’re really experimental y’know, you probably wouldn’t get it.

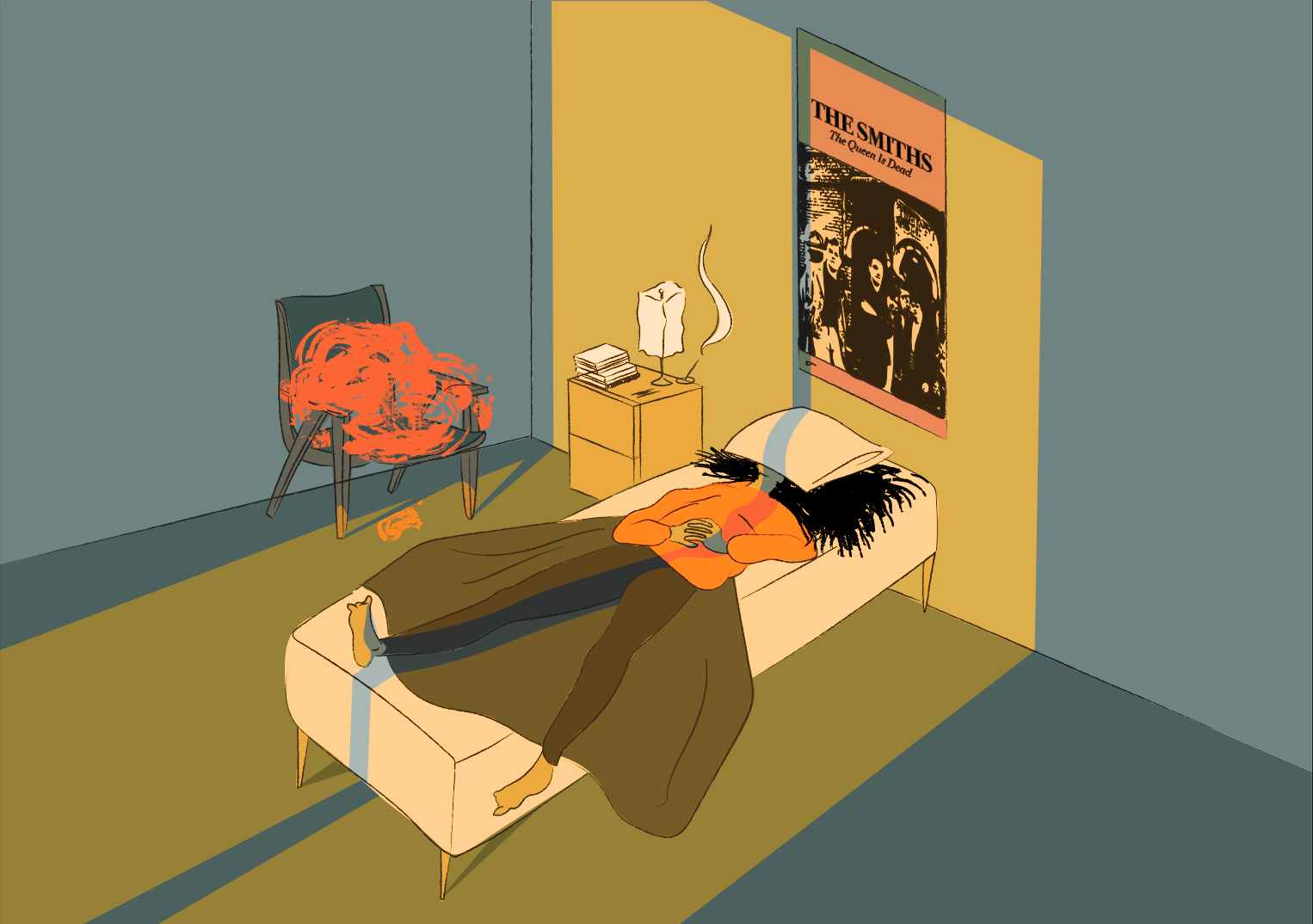

While I’m sure this brand of interaction has happened to many women in alt music scenes (I’ve definitely met my share of pretentious music bros), this sort of exaggeratedly misogynistic conversation has become more of a meme than anything. Online spaces love to continue rehashing the “indie music bro”/“softboy” archetype that’s been popular for around five or so years now. However, recently he’s gotten a more nefarious makeover: the male manipulator.

The hashtag “male manipulator music” has 18.6 million views on TikTok, so what exactly are the teens talking about?

Trying to pin down what artists are considered “male manipulator music” is a fool’s errand. When going down the rabbithole of TikToks and Spotify playlists, additions of bands like The Smiths may lure you into a sense of understanding. The band is largely connected to media portrayals of the so-called male manipulators in 500 Days of Summer and High Fidelity, not to mention frontman Morrisey’s fascistic tendencies.

But as you go deeper, you’ll see acts with otherwise tame public reputations such as Radiohead, Neutral Milk Hotel and Slowdive, taking up a bulk of the spots. Go even deeper, and you’ll encounter the truly baffling additions of female fronted acts such as Metric, Beach House and Phoebe Bridgers.

What do any of these acts have in common? Basically, just some indie cred and a completely arbitrary label used to ascribe immorality to music taste.

Many of the videos under the TikTok hashtag follow a similar format. They include either joking skits or videos flipping through records with the caption “POV: you manipulate women.” Also common is a trend of ranking bands and singing along to audio of so-called male manipulator music containing Mac DeMarco, My Bloody Valentine and Tyler, the Creator, to name a few.

While it may all seem in good fun, there is something very sinister about manipulative relationships and even gaslighting being mapped onto music taste.

Firstly, the notion that you could determine which men are “safe” and which are “red flags” simply by their style and music taste is incredibly harmful. There is no singular archetype of a person who is abusive and toxic, and pretending like you can guess which men pose a threat from outside indicators can lure women into a false sense of security. Honestly, a man who listens to EDM is just as likely to be a jerk as one who listens to shoegaze. A lot of the posts under this TikTok hashtag come from teenage girls and young women, and it could be giving false notions of how relationships should look.

On top of that, the mere idea of ascribing morality to music taste is slippery at best. For the most part, in the manipulator music discourse, this isn’t a case of separating the art from the artist. Sure, some “male manipulator music” comes from toxic men, such as the aforementioned Smiths or Sorority Noise, but the majority of artists given this title are labeled such for seemingly arbitrary reasons.

There is an argument to be made that if a consumer continues to support artists they know to be bad people, part of that blame gets conferred onto them. Yet, how has that argument gotten twisted into ascribing malintention when supporting squeaky clean artists with a subjective “red flag” vibe?

Further, this puts female music fans in a tricky situation. When Joy Division, for example, becomes music for gross men, where does it place us women who hold a tenderness for it? Labeling these artists as “male manipulator music” ultimately labels them as for men.

The issue of male manipulator music may seem inconsequential, but labels can be impactful. As a culture, we’re already so steeped in the notion that the media you consume tells deeper secrets about who you are as a person. Rather than leaning so heavily into that notion, let’s try taking a step back and not micro-labeling and psychoanalyzing Spotify playlists.

Graphic by Lily Cowper.