A group of TikTok creators are embracing hyperfemininity while rejecting internalized misogyny and the male gaze

In recent years, words like “bitch” and “slut” have undergone a transformation. “Bimbo” used to be a misogynistic insult, connoting an attractive but unintelligent woman. But now it is the latest word in “girl world” to go from demeaning to empowering. On TikTok, bimbos are trending. This proud new breed has embraced the identity of a new-age bimbo while sporting a pink Y2K aesthetic, worshipping icons Dolly Parton and Anna Nicole Smith, and preaching leftist values.

“A neo-bimbo unironically loves hyper-feminine fashion, jewelry and aesthetics in the face of a patriarchal institution that would deem them frivolous,” explains Bunny, who goes by the handle @bunnythebimbo. She has gained a following by making videos where she teaches classes on what she has coined as “bimbology.” Having recently graduated with a Women and Gender Studies degree from Chatham University, she loves to analyze what being a new-age bimbo means from a theoretical perspective. In one post on her Tiktok, she says bimbos take their femininity to the extreme as a way of making fun of how men perceive them in this patriarchal society. “But also we’re taking part and pleasure in it so it’s once again ours,” she points out.

Twenty-three-year-old Tennessean Hannah Foran, a.k.a. @parishiltonslefttitty, enjoys being able to dress for the male gaze, even if she’s subverting it. Ever since she was little, she’s admired the Y2K aesthetic. Known for her platinum blonde hair, plump lips, Juicy Couture, and cleavage, she says, “To me, being a new-age bimbo means you’re flipping the ‘male gaze’ on itself. You are becoming the very thing that men fear; a promiscuous, very attractive woman who plays dumb but is actually very smart once she reveals all her cards.”

New Yorker Meredith Suzuki (@maeultra) recently started to embrace being a goth-bimbo, a type of bimbo who has a darker aesthetic than the stereotypical pink.

“We are hot bitches who choose to be dumb, not just because some annoying idiot man made them like that,” she says in one clip on her TikTok. The 24-year-old believes the pandemic and capitalism pushed her towards bimboism. She became increasingly frustrated with how much more mental and emotional labour women have to do.“I wanted to break away from all that,” she says. One day she woke up and decided that she just wanted to be hot instead.

Perhaps the most successful bimbo on TikTok, Chrissy Chlapecka, 20, has attracted more than two million followers to her account, @chrissychlapecka. In a recent video, she frolics through the streets of a wintery Chicago in a thin coat unzipped to show off a pink fluffy bra. “Sweetheart, this is a sign to wear whatever the hell you want,” she tells her audience. “I don’t care if it’s snowing! Winter is a concept!” Her account is filled with videos where she’s either screaming at viewers to stop being sad over some mediocre boy, making fun of Trump supporters, or discussing how bad she is at math. Chlapecka famously finishes each of her captions to her videos with “#ihatecapitalism.”

Fifty-one-year-old Ginger Willson Pate, @glitterparis, is one of the older bimbos on the app. Her favourite part of being a bimbo is how often she’s underestimated because of her looks. She claims it has worked to her advantage in her life. Along with her daily TikTok videos, she’s a real estate agent in Silicon Valley and has a business with her partner of flipping and selling houses.

“That’s been a really lucrative career for me,” she points out, “so I’m not as stupid as I look.”

To Pate, being a bimbo means she doesn’t have to be ashamed of being ultra-girly and materialistic. “I’ve actually been put down for that by men that I’ve dated,” she says. But she’s happy the way she is. “I’m not gonna tone it down for some guy’s opinion of me,” she explains.

In the past, Concordia Journalism and Creative Writing student Nadia Trudel has struggled with letting herself care about her appearance, while simultaneously wanting to be an intelligent young woman.

“I think seeing these TikToks has encouraged me to be more unapologetically confident and take pride in my appearance without feeling shallow,” she says. Being smart and caring about your appearance had always seemed like two incompatible concepts. She’d been taught to value being smart and dislike girls who cared about their appearance. But now, she recognizes that belief system to be internalized misogyny.

Emma Amar, a Concordia Software Engineering student, categorizes the bimbo movement as a feminist movement. She believes that modern day feminism typically rejects stereotypically feminine things. As Gen Z, we are the daughters of the mothers who wouldn’t let us play with Barbies.

“Publicly deciding to embrace those qualities and still be a feminist, or still be politically informed, is really powerful because it shows that the way you look does not automatically decide how smart or informed you are,” explains Amar.

“Do you support all women regardless of their job title and if they have plastic surgery or body modifications?” Syrena (@fauxrich) asks in a TikTok video about the requirements to be a bimbo. While Syrena has not gotten any work done yet, the 22-year-old is currently studying to become a cosmetic injector.

Foran, @parishiltonslefttitty, openly admits that she had her breasts done in exchange for spanking a sugar daddy with a paddle in a leopard thong. She has blackmailed sugar daddies that were married in order to get free Botox and lip filler. “I want my nose done next,” she adds.

Ultimately, bimbos have created a safe and inclusive space on the internet where one can be themselves without judgement.

“She’s actually a radical leftist who is pro sex work, pro Black Lives Matter, pro LGBTQ+, pro choice,” Chlapecka explains in a TikTok video about the role of the bimbo, ”and will always be there for her girls, gays and theys.” While Chlapecka has progressive values, she still, as a blonde thin white woman, perfectly fits the original bimbo aesthetic from a decade ago from reality tv shows such as The Simple Life and The Girls Next Door.

Despite the progressive message of bimbo TikTok, Amar doesn’t believe that the community is sufficiently diverse. She has mostly come across white women on bimbo Tiktok.

“But I think that has a lot to do with TikTok’s algorithm,” she says. Bunny, who is a self-proclaimed fat white woman bimbo, says she’d also like to see more accounts uplifting POC and fat creators. “I think that creating your own aesthetic despite restrictions that say that you cannot be a part of it is something that can be really powerful,” Bunny explains about her own journey of embracing the bimbo aesthetic as a fat woman.

“The definition has expanded to become much more inclusive of all genders, races, body types, sexual orientations and aesthetics,” says Suzuki. In 2021, bimbo no longer just describes ditzy white blonde girls with big boobs. If that were the case, Suzuki wouldn’t be here. She’s proud of how far Gen Z bimbos have come when it comes to inclusivity and diversity. “But this is really only the beginning.”

Many bimbo creators have gotten comments from their followers claiming they want to be a bimbo but they don’t have big boobs or they don’t have the right sort of clothes. “A neo-bimbo needs to be hot, but that is not deemed by patriarchal beauty standards,” explains Bunny, “but rather by an unapologetic confidence that radiates from within.” Bunny strongly believes that anyone can be a bimbo.

Both Amar and Trudel say that since starting to watch bimbo TikToks, they have gained confidence. “It’s okay to just be like ‘I’m sexy, I’m hot,’’ Trudel says. “And it can be fully serious, or it can be kind of ironic.” To her, it seems like there’s an almost fake it till you make it quality to gaining confidence as a bimbo. “If you start acting like you are sexy and calling yourself sexy, maybe you’ll start to actually feel that way,” she explains.

Amar sometimes gets nervous about dressing in revealing clothes out of fear that others will judge her and think she looks slutty. Seeing bimbo creators dress unapologetically in hyperfeminine or hypersexual outfits has helped her become more comfortable. “It reminds me it’s okay to express myself in whatever way I want to,” she says.

While on the exterior, the bimbo movement on TikTok might seem like simply a pink aesthetic and pretty girls, it’s so much more. Syrena states that being a bimbo, at the end of the day, is a lifestyle grounded in kindness. “Loving yourself and refraining from judging others too quickly,” says Syrena, “That is the most important part of being a bimbo.”

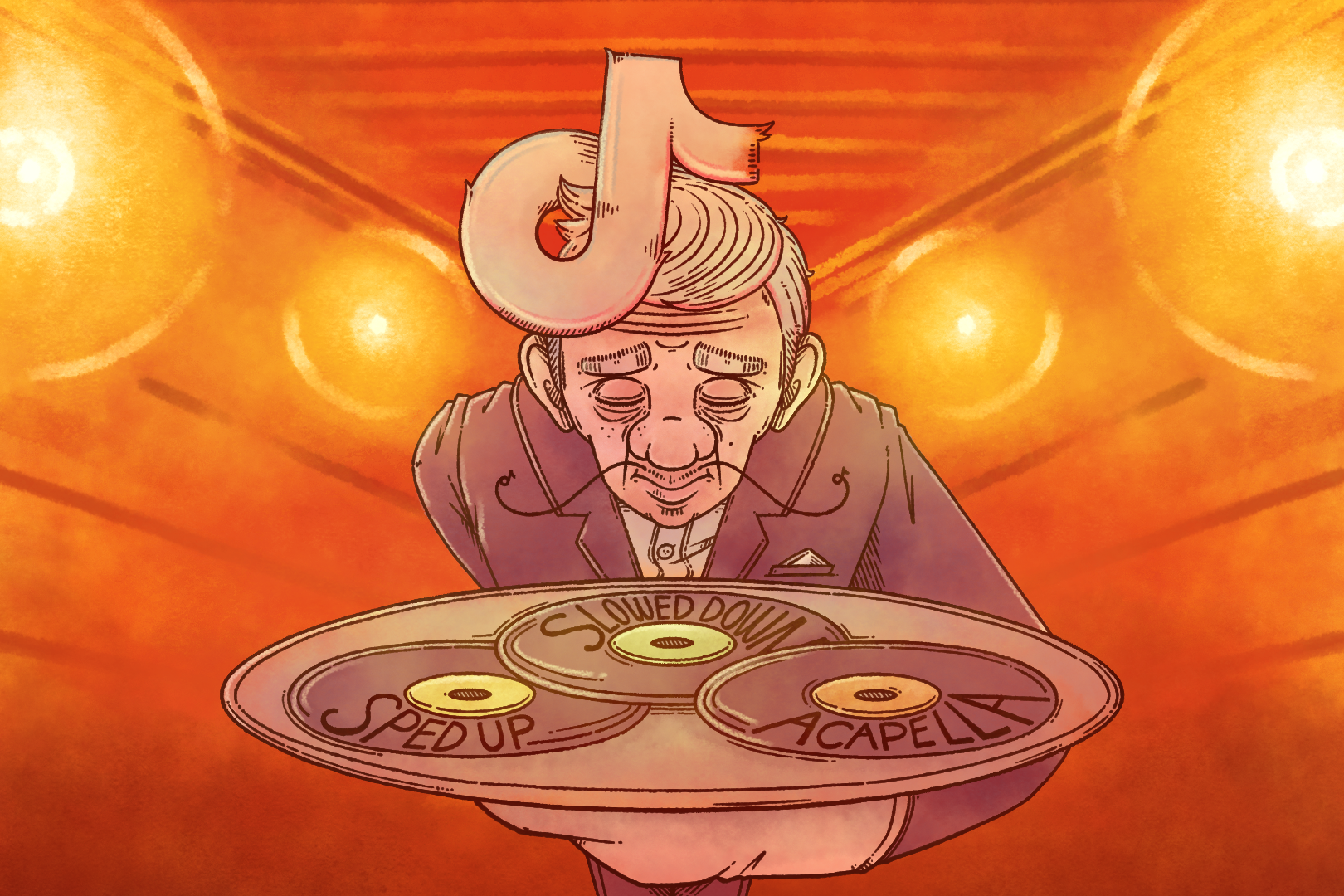

Graphic by @the.beta.lab