A tale of two climate crises and how the effects of climate change differs across the world.

The first time I experienced temperatures above forty degrees Celsius was in July while I was representing Concordia at the Thessaloniki International Media Summer Academy in Greece. The second was two weeks ago after a heatwave in Montreal and parts of Quebec caused the city to experience record-high temperatures.

When I look back on this past summer, it seems that every significant experience that I had was somehow underscored by climate catastrophes. Whether it was going to the park while Montreal had the worst air quality in the world or exploring the CJ building as it flooded, it’s a stark reminder that the climate crisis is a part of our new reality.

Before this summer, my views on climate change could be summarised by the phrase “optimistic ignorance.” Don’t get me wrong, I knew that climate change was a major challenge facing humanity and would require tremendous social action to combat its worst of its ramifications. And yet, I still believed that the dire warnings of climate scientists espoused of dead zones and societal collapse would not come to pass.

The cognitive dissonance required to hold these two positions simultaneously could only come through my privilege and background. Experiencing the effects of climate change in two vastly different countries has provided me with a unique understanding of how our collective understanding of the climate crisis reflects our circumstances.

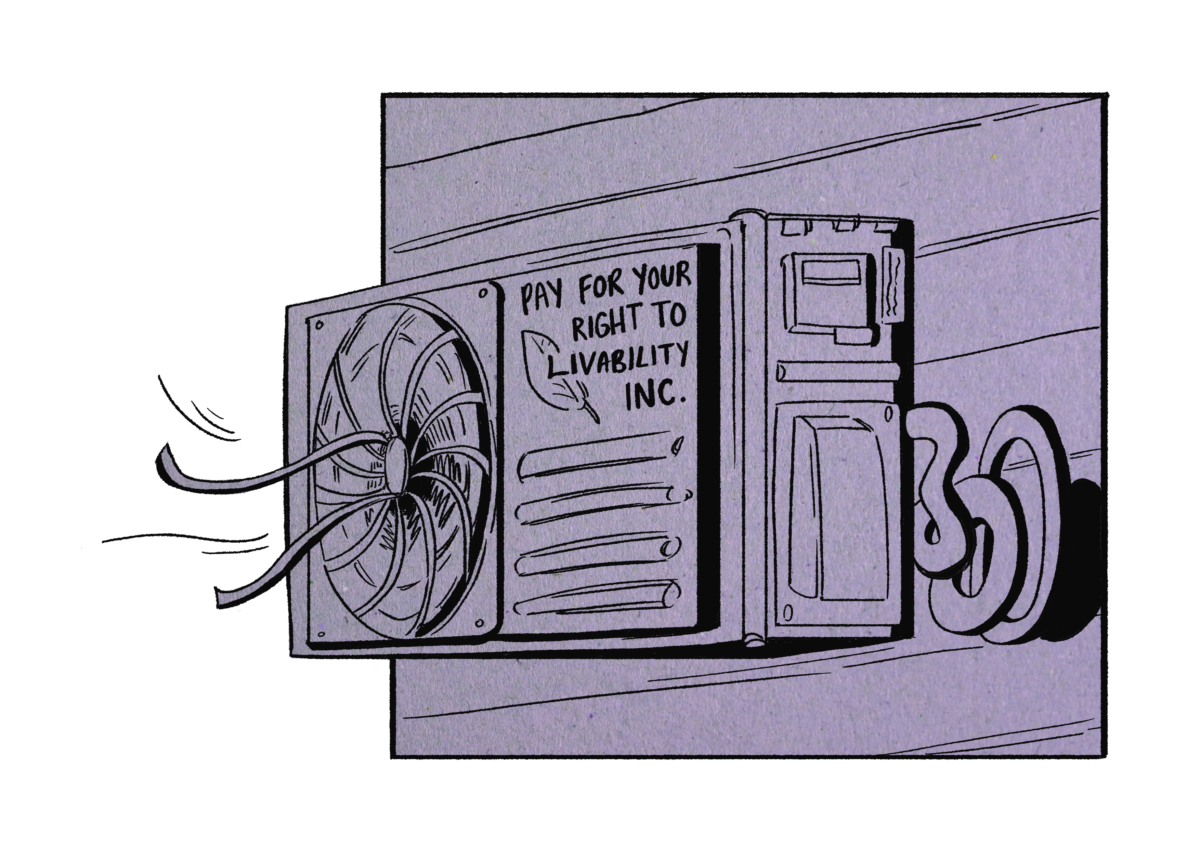

In Quebec, the public’s response to record high temperatures was to demand for the provincial government to service all public schools with air conditioning. Meanwhile, in Greece, I watched as the people were forced to adapt their lifestyles to deal with the heat. Businesses and social services would close during the highest heat of the midday sun.

The most startling example of this occurred when I was in Athens during the peak of July’s heatwave. As I walked down the street, my self-centred concerns, anxieties, and frustrations regarding the temperatures were quickly humbled when I came across a refugee struggling to find shade in the city. Beside her was a young girl, barely over the age of 10, wearing a pitch black robe lying in the middle of the street, too weak to sit up.

It was the first interaction I had with displaced peoples. It’s a scene that still haunts me to this day, a reality that most of us in the Global North will be sheltered from. A reality that has permanently altered my relationship to the climate crisis.

Despite my newfound perception of the climate crisis, I refuse to partake in climate nihilism, or the mindset that nothing can or will be done to address the current crisis. It’s infuriating to witness those in the Global North, who enjoy the advantages of our modern world while being shielded from the repercussions of their actions, readily accepting defeat.

It’s up to us to engage in the hard work that is needed to bring social and infrastructure reform to mitigate the worst effects of the climate crisis and embrace the sacrifices to our personal lives that will come with said changes. At the very least, we owe it to those who are the most affected to not give up.