Wear black. Avoid horizontal lines. Put your hair in a bun. Drink tea. Eat less.

Considering weight gain like a plague has made us overlook the fact that comments made non-maliciously can still be traumatizing. Why are we so deeply afraid to become fat? Why are we so afraid of our loved ones being fat?

Six years ago, during a family dinner, Marie-Noëlle Hébert’s father told her that she had eaten enough. It was nothing like saying “you are too fat,” but the cruelty was, innocently, the same. While the then 23-year-old thought she was happy with her body, that comment left her deeply horrified and led to a spiral of doubt and depression.

You have eaten enough.

Yet, this painful feeling was not unknown to Hébert. This time, she wanted to understand how it all began. She started to investigate her old journals and asked her relatives to share memories regarding her weight.

“I asked my mother when did she first notice that I was fat, but also when she noticed that I started to see it too,” Hébert said. “It was as if I buried, deep down, all these episodes of being ashamed of my body. I had forgotten things and now I wanted to be reminded.”

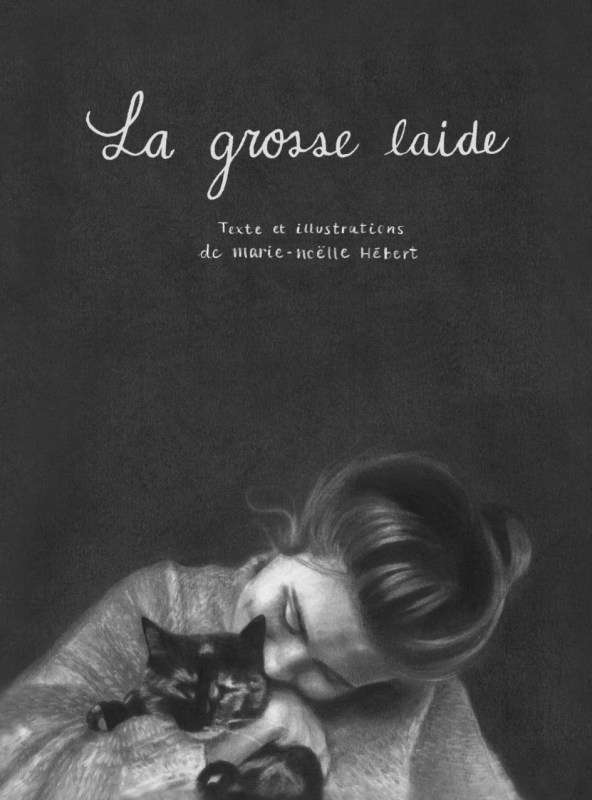

As a result, Hébert embarked on a journey that led to the creation of her first comic book, La Grosse Laide, a redemption of self esteem and fat phobia. Reading through her old journals might have been inspiring, but it was still very hurtful for her. They were filled with dark and suicidal thoughts with a recurring theme: she considered herself to be a fat, ugly person.

La Grosse Laide.

The truth is, Hébert is not alone. Fat phobia represents the fear of being fat or seeing fat around you. According to the National Eating Disorder Organization, the phobia is strongly present in girls from ages six to 12, with 40 to 60 per cent concerned about their weight or are fearful of becoming fat. This time coincides with their bodies going through extreme changes, mostly due to menstruation shifting hormone balance. Yet, this time is often received with teasing by family and friends.

“I was surrounded by comments on my body either at home or school — it was inevitable,” said Hébert. “Comments about what I ate, what I was wearing and the infamous culture of shaming pasta-bread-potato. In my family, there are a lot of women; it’s an entire network where you can’t be fat, nor vulgar. You can’t speak too loud or be spontaneous. You had to be feminine and delicate. But these comments were often made as a joke or trying to help, never in a malicious way. Truly, it usually is a reflection of the person’s fear of their own body.”

Is fat phobia intergenerational then? Hébert recalled her father often swimming with his t-shirt on. She realized how his own fight with body image was why he was verbally violent towards her. Undeniably, such vituperation and influence from Hebert’s family is palpable through her soft voice and tender laugh. Her kind eyes tell the story of a long fight against self-shame — an all-too-common look.

La Grosse Laide is not a way for Hébert to shame her entourage; rather, it is an autobiographical testimony. It is a way to finally redeem herself and transform her body issues into something artistic and beautiful. For someone who never published her drawings, it is an incredibly personal project, as the notion of being fat can be.

Indeed, it is difficult to have a single description of what it means to be fat. Categorizing obesity is easier since it falls under body mass index measurements, determined by the Heart Foundation. Body dysmorphia, which usually derives from fat phobia, can’t be calculated and fixed through a scale. A study at University College London showed that the brain believes the body to be two-thirds bigger than it actually is. Becoming comfortable with your body is not a one-day process and can take a lifetime to overcome, according to Hébert.

“While I was working on my comic book, I was living in Montreal with my grandmother, whom I love dearly,” said Hébert. “She is proud of her appearance and has always been obsessed with her image and weight. Living with her, I saw where [my own obsession] came from. At 80 years old, she was still hating her stomach. If there is a fight that I will drop, it is this one. I don’t want to find my old self still saying ‘goddamn stomach!’”

Ironically, while creating La Grosse Laide and working full-time for the STM, Hébert recognized having gained weight. As her comic book comes as a critique of fat phobia, she now finds herself having to tame and love her 29-year-old body. Yet, when she draws, she doesn’t think about her body rolls. Her focus is not on her physique anymore. There is no weight-loss plan in her life, no obsession.

There is only her graphite pencil and her drawings to achieve body reconciliation.

La Grosse Laide is available at XYZ Edition.

Photo courtesy of Marie-Noëlle Hébert