There’s a cry for artistic freedom in the Academy-Award-winning director’s latest rant that sympathizers and dissenters alike should find common ground with.

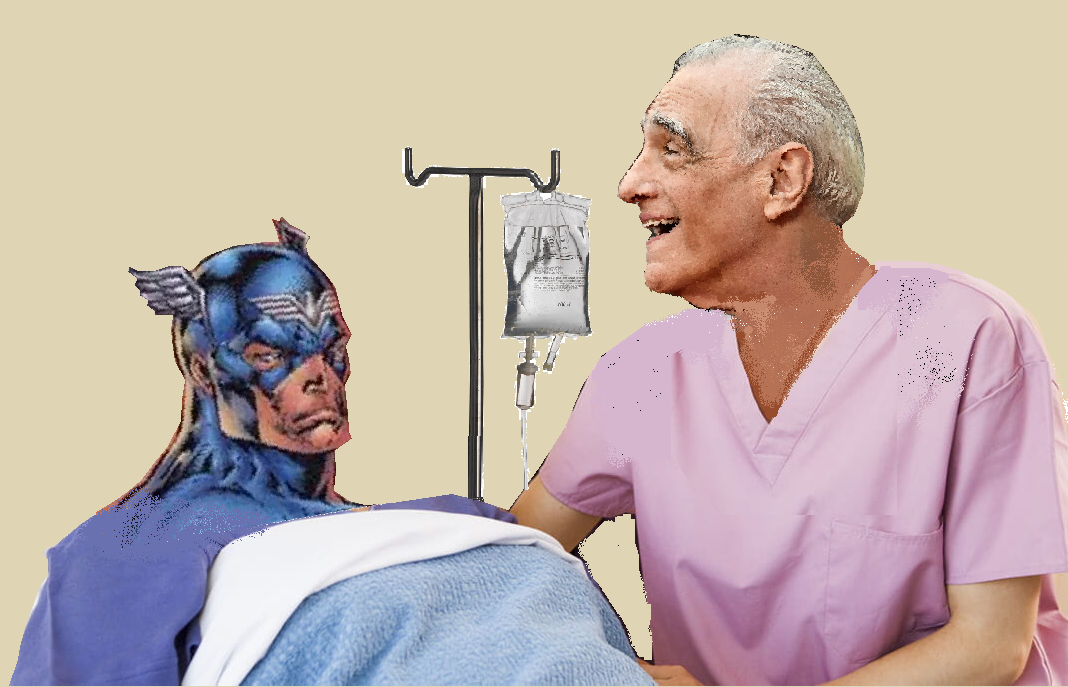

Martin Scorsese is yet again bemoaning the sweeping influence and thronging presence of Marvel movies in the modern cinema. In pre-pandemic years, Scorsese had lamented that the characters in these films lack complexity, the plot stakes are illegitimate, and that they provoke neither novel reflection nor genuine emotion for the viewer. In a recent interview with British GQ, Scorsese reiterated with more grave urgency the need for a radical upheaval in the industry.

As he sees it, true cinema is a dwindling art form—surviving only by virtue of legacy filmmakers, like the Safdie brothers and Christopher Nolan—that must be rescued from the grips of increasingly parochial executives lest a new generation come to view blockbusters as the cinematic standard.

It is far too tempting to dismiss his polemic as yet another quasi-existential fret on the part of an octogenarian who refuses to come to terms with changing tides and generational proclivities. And this would be in many ways correct. Scorsese’s assessment of Marvel movies crowding local theaters is largely exaggerated—we typically receive only a couple of them each year. His casual assumption that all films within the genre are essentially indistinguishable from one another is demonstrably crass, for there are notable character-driven complexities to be found in Marvel’s cinematic universe when we pay close attention. While there is something to be said for the lack of “real danger” posed to many of Marvel’s heroes, the happily-ever-after eludes many of them, as evidenced by the bittersweet conclusions to Avengers: Endgame and Spider-Man: No Way Home.

Scorsese himself is renowned for directing several classic gangster movies. Prior to The Godfather, the predominant view of these films was equally as dismal as Scorsese’s perception of the superhero genre, as they were commonly decried for their glorification of crime and even denied the honorific of “art.” Coppola, Scorsese, and others in that lineage redefined what “real” cinema came to be understood as.

If Scorsese’s gripe with superhero movies has to do with a perceived simplicity of character and narrative, we would need to throw out a great deal of films produced every year. And even so, who should we then designate as the arbiter for the requisite degree of sophistication a production must exhibit to qualify as “true cinema?”

Yet Scorsese’s sorrow is not unjustified. It is incontestably true that filmmakers are being constricted and prodded to respond to market interests in increasingly narrower ways. Even as decorated a filmmaker as Scorsese himself was left with no other resort than releasing The Irishman as a Netflix exclusive, for no other outlet would grant him the big screen while producing the film in the manner he intended – that is, to have the freedom to make creative decisions without having to consider the needs of an endless franchise. Scorsese lamented to British GQ about his experience with Warner Brothers when producing The Departed, noting that executives were more concerned with the potential for sequels than the integrity of the story Scorcese wanted to tell.

Increasingly intolerant attention spans have exacerbated the demand for fast-paced plots instead of character-driven narratives—something that, as Endgame’s director Joe Russo acknowledged, has impacted the direction of the Marvel franchise. James Gunn, who directed the Guardians of the Galaxy trilogy, expressed similar laments, saying that “Movies in general are not as good as they used to be” as a result of the creative inhibitions that film executives have saddled writers with.

It is, therefore, not strictly Scorsese versus Marvel, but rather a clash between creatives and an industry that seeks to commodify art. It is pointless to engage in semantic gatekeeping over what constitutes “true cinema,” and one need not agree with Scorsese on every level—he is in many ways mistaken—to recognize in his words a plea for upholding cinema as an art form instead of an adaptive commodity.