The music industry’s latest tactic capitalizes on hit potential—but at what cost?

In the late 2010s, TikTok truly established itself as a pivotal force in the music industry. It helped several songs grow rapidly in popularity, granting the platform its status as a hit factory. There was the runaway success of Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road” in 2019, which went on to become the longest running #1 in Billboard Hot 100 history, and tracks have since found their way onto the top 10 of the charts starting from TikTok.

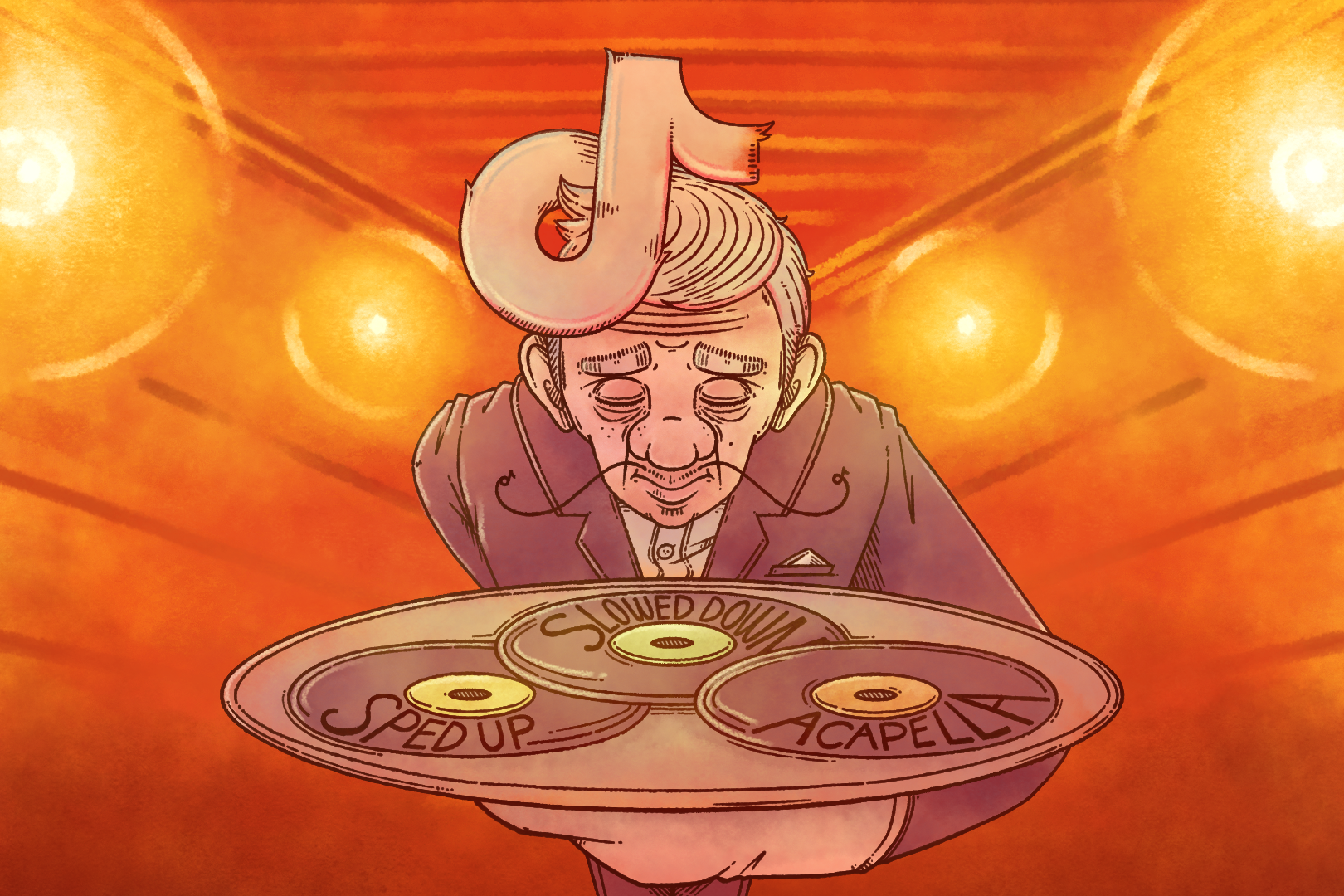

The music industry found new ways to adapt, with the concept of “versions” resurfacing as a way of maximizing success on the platform. The practice consists of releasing several variations of the same song or album, with differences in pitch and speed, or even deconstructed versions.

The release of alternate versions is far from a new concept. It has long served as a “fans-first” method for artists and their audience to revisit and reimagine existing projects. Artist-producers like Metro Boomin and Tyler, The Creator have notably released the instrumentals to their albums to highlight their production. A cappella and instrumental versions of songs notably open the door to creative opportunities for musicians.

Concordia communications student and producer Theo Andreville notes that these versions are longed for by DJs looking to remix songs, producers trying to remake beats and rappers looking to record remixes (which defined hip-hop mixtape culture in the 2010s).

For local singer Marzmates, they are also a teaching moment in which she gets to notice the intricacies of a beat, the way the vocals are mixed, and the technicalities behind the singing.

Andreville also supports artists releasing a larger output of the same song as it results in a greater financial gain for them: “It makes sense—you’re already being paid pennies on the dollar.”

Sped-up and slowed-down songs are two of the most common styles, and their popularity predates TikTok entirely. Forbes reported that the app’s most popular songs in 2023 were sped-up remixes. Both Andreville and Marzmates agree that these edits can breathe a new and unique life into an existing track because they bring a totally different vibe.

With record labels throwing their hat into the ring, versions are now being mass-released in an attempt to chase hits and make more money off artists, jeopardizing creative control. British singer James Blake recently made headlines for an Instagram post on March 2 addressing the topic. He stressed the problematic nature of the focus shifting from the art towards viral moments. “We have to be great at social media but not really need to be great at music, the ‘working’ of songs now meaning posting infinite videos with the same clip of the same song,” the vocalist stated.

Certain labels and artists are pushing the concept to extremes. Ariana Grande recently reissued her hit single “yes, and?” with a whopping eight versions: the original, radio edit, extended mix, sped up, acapella, slowed, instrumental and extended instrumental versions. The technique is also being applied to entire albums: 21 Savage’s american dream was given a slowed, nightcore and sped up version within two days of the original’s release.

Communications student Jade Dubreuil also takes TikTok’s fast-paced nature and consumer culture into account. “From a business standpoint, it’s extremely smart—but it creates fads. Artists who take that route take risks.” TikTok creates hits with ease, but shaking the “TikTok song” label is a much stickier situation.

Despite now flooding the market due to corporate greed, versions are widening the window of opportunity for creators and executives alike. “It’s more of a service to everybody, even if it’s redundant,” Andreville concludes.