Taking an exam shouldn’t mean giving up your privacy

Concordia University’s OnLine Exam (COLE) system, which uses Proctorio’s technology, has received much backlash online, and rightly so. The platform helps to facilitate evaluations even if students cannot physically be present on campus, an unfortunate reality for many amidst our current COVID-19 pandemic world. However, by using Proctorio’s assets, universities are setting a dangerous precedent. One University of Dallas student journalist put it as “spyware cloaked under the guise of being an educational tool.” From knowing what tabs you have open, direct access to your camera and microphone, the ability to see what devices you have plugged in and eject them, it’s an unprecedented amount of power forced by universities onto already pressured students.

Before I go further, I want to emphasize that academic integrity is essential. Cheaters ruin our world, whether through traffic, shoddy quality goods, relationships, or taxes. Academia has a responsibility to protect itself against this, but not just because it hurts other students and our work. Ultimately, how we conduct ourselves in our schooling is how we approach our workplaces and our communities.

But enough is enough. The line was crossed months ago, and the excuse of COVID-19 simply isn’t good enough. These privacy concerns were already discussed at the start of the pandemic. In an April 7 Medium article, a former Bay Street lawyer (and Concordia alumnus), Fahad Diwan, broke down exactly how the university was violating student rights in a legal context. Shocker — he thinks it’s wrong and maybe even illegal.

“The use of Proctorio needs to be suspended until Proctorio can get manifest, free, and enlightened consent from students,” said Diwan in the post, “and Concordia University can demonstrate that online, closed-book exams are absolutely necessary.”

Well, that didn’t happen. The administration and faculties washed their hands of the controversy with the same excuse everyone is using — it’s COVID.

Let me ask my fellow educators and administrators — would you consent to this? Would you accept Concordia creeping into your computer, your files, your emails? And I’m not talking about your work machines. I’m talking about your personal tech because that’s what Proctorio does to students through their pervasive Chrome extension. Maybe you do because you have “nothing to hide.” And if that’s the case, I encourage you to post your login credentials publicly on your social media so we can all see why you are such a good netizen (please don’t do this — it’s against Concordia security policies, but also super stupid). This attitude is stunningly anachronistic that I feel genuine shame for those who utter it. Your computer, your phone, your tech IS YOUR BUSINESS.

But let’s go further: what if you were required to report your GPS location for every class you taught because the university told you they needed to verify where you were working for tax purposes? After COVID, what if they monitored when and where you were in the building because your phone automatically connects to Concordia’s wireless network? What if they said you needed to record all lectures and submit them to the university, where an independent team including students would assess if you were effective in teaching during your class discourse, as well as scanning for other problematic behaviour? What happens when you are required by Instructional and Information Technology Services (IITS) to install software that would monitor your productivity? What’s sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander.

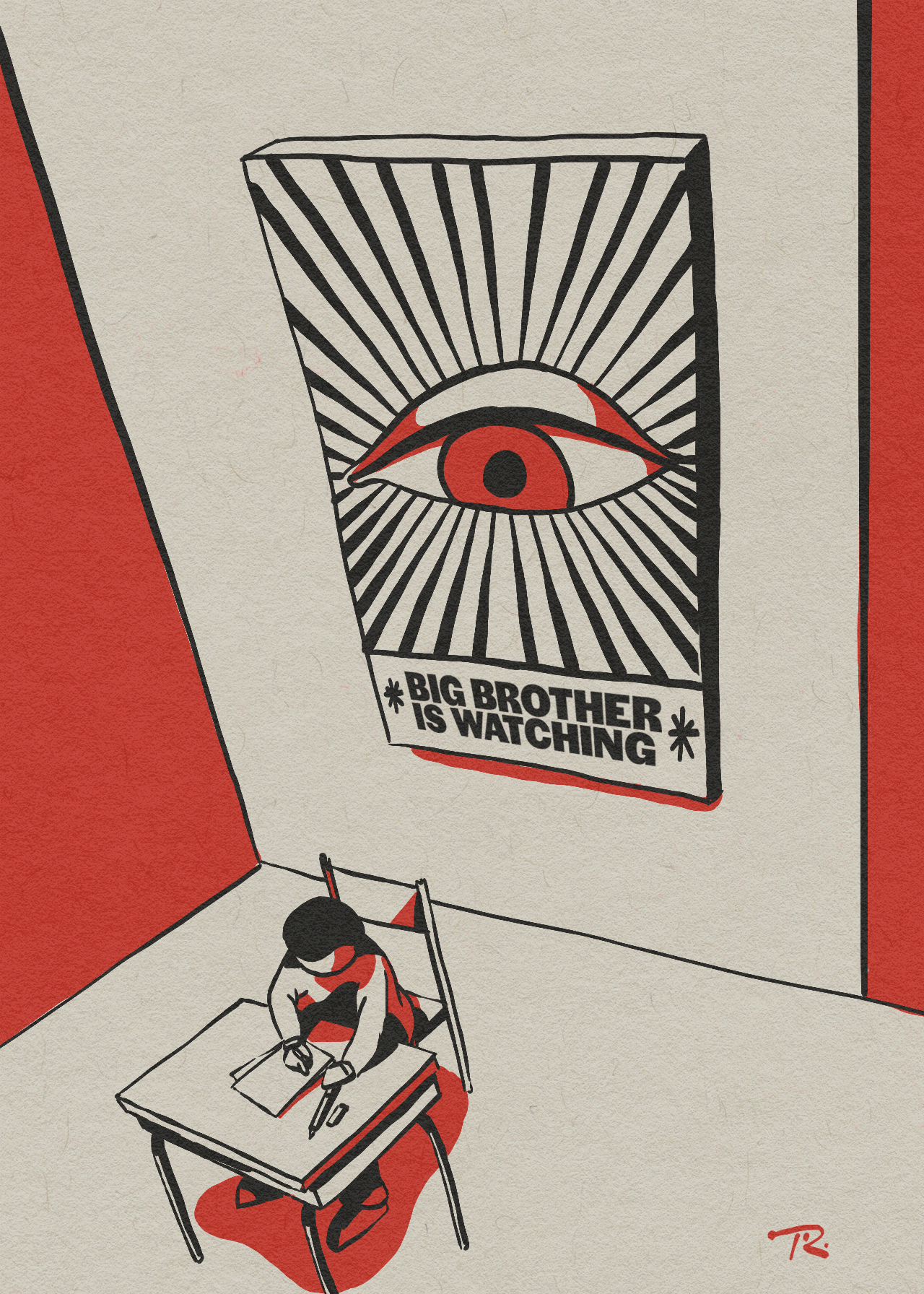

These are no longer “what ifs.” They are WHENs. Like I said before, school environments dictate how we conduct ourselves in our communities and workplaces. By insisting students use these platforms instead of exploring alternative evaluation methods and being unwilling to show empathy for students, academia will receive the same fate. But what’s worse is that universities are setting up the digital prisons they so often rail against. How come Foucault’s panopticon, widely taught in the humanities, did not at least come up in the conversation when implementing this Orwellian spy apparatus?

I beg this: is it worth protecting against cheats if it makes you lose your soul? We’re not police officers — we’re educators. We seek to empower our students, not wield power over them. Worse, we tell the world and every employer that these tactics are acceptable and to use them on the next generation of workers.

You might feel powerless in this situation. But students have the agency to resist. So, if you are taking exams this semester with COLE or with any system that uses Proctorio or other invasive technologies, fight back! Put a sign in your room or wear a T-shirt that says #ScrewCole or #ExamsNotProctology. It’s your right to free expression.

Before taking your exams, post photos on your social media and tag local media and journalists — encourage your friends and classmates to do the same. Because having to take a university exam shouldn’t mean your school gets to look through your life, digital or otherwise.

Graphic by Taylor Reddam