As an earthquake shook Morocco, Moroccan students were faced by the difficulty of finding news and support.

Yasmina May Hafiz, a Concordia third-year international student from Morocco, vividly recalls the moment she received the delayed news from her home country nearly four hours after the earthquake hit on the night of Sept. 8.

“I received a call, so I’m thinking my friend just wants to chat, and they immediately say: ‘Hey, have you called your family? Have you contacted anyone that’s in Morocco right now? There was just an earthquake,’” Hafiz said.

Taken aback, she quickly hung up the phone, entering an immediate state of panic. “I didn’t know the magnitude. I didn’t know what city it hit. I didn’t know any details,” she said.

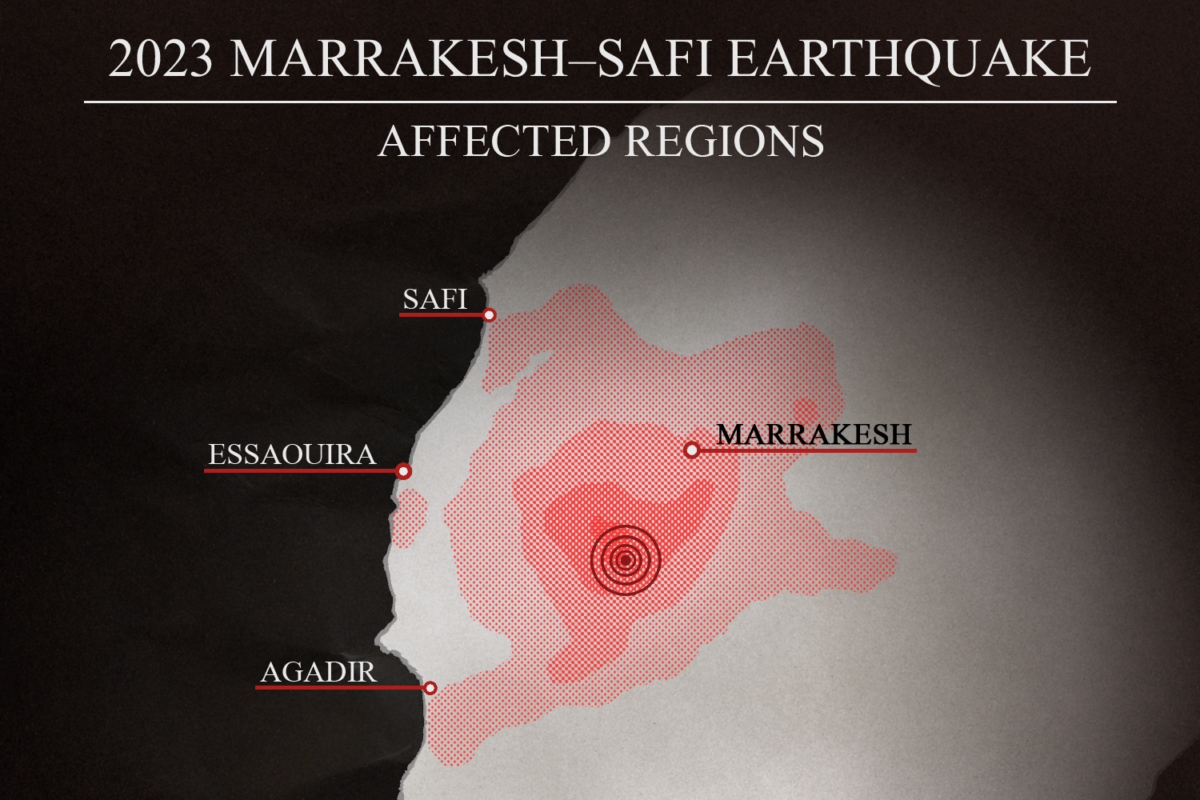

On Sept. 8, a 6.8 magnitude earthquake struck Morocco’s Atlas Mountains before midnight, killing nearly 3,000 people and injuring thousands more.

Canada’s recent implementation of Bill C-18, which has resulted in news content being blocked on social media, has made times of crisis even harder after Morocco’s earthquake.

It took almost 40 minutes for Hafiz to reach her family in Casablanca, as her mother’s phone died and local cell towers were down. Her father happened to pick up while out of town in Algeria, reassuring her that her family was safe.

“I just had to calm myself down and be like, ‘Okay, I’ve talked to everyone. They’re okay. Like repeating to myself I’ve heard their voices,’” Hafiz said.

Hafiz spent the majority of her life in Casablanca, alongside her parents and younger brother.

In 2021, at 18 years old, she moved to Montreal to study communications and cultural studies at Concordia. While this opened a new chapter in her life, it took her some time to navigate her lifestyle in the city. Part of this change required her to find a way to stay up to date with local news from her hometown.

She found herself relying on local Moroccan news outlets’ social media pages. To her, this was a perfect way to passively consume information with limited effort.

This routine didn’t last too long.

In June, Canada introduced Bill C-18, which requires big tech companies, such as Google and Meta, to compensate Canadian media organizations for using their social platforms. On Aug. 1, Meta responded to the bill by blocking most news content on Facebook and Instagram across Canada.

For those like Hafiz, who depended on social media as her primary source of local news outside of the country, Bill C-18 created barriers that became most noticeable in times of crisis.

Matthew Johnson is the Director of Education at MediaSmarts, a digital media literacy non-profit organization based in Ottawa. MediaSmarts defines digital media literacy as “the ability to critically, effectively and responsibly access, use, understand and engage with media of all kinds.”

He referred to the obstacles faced by wildfire evacuees in Yellowknife this summer, who had limited access to emergency news updates on Meta’s platforms.

“That made it very difficult for many people to share what was happening to them. And in parts of Canada, where there’s limited access, in some cases to TV or radio news, it does seem as though it did have a significant impact,” Johnson said.

These limitations may also impact those who rely on news from outside of Canada, with limited access to broadcast or print from other countries. “The real question is, what’s going to happen when and if Google starts doing the same thing?” Johnson asked.

Johnson emphasized the importance of not putting all of one’s informational eggs in the same basket. He advised readers to curate their news sources from outside of social media platforms, ensuring to list those that they can rely on, especially in times of crisis.

Despite Concordia students facing limited access to news on social media, they still found ways to spread information on Instagram.

Selma Idrissi Kaitouni was raised in Casablanca and moved to Montreal last year to pursue her studies at Concordia’s John Molson School of Business. The student was in Montreal with her mother when the earthquake hit, but her father was in Marrakesh. Her family hasn’t been affected.

A few days after the earthquake, Idrissi Kaitouni and her friends came together to form a social club called the Moroccan Student Union (MSU), to advocate for those affected by the crisis.

The club aims to become an official student group by completing the university’s registration process. “We really want to start embracing Moroccan culture at Concordia, whether it’s during Ramadan or it’s just having a safe place to be when you’re very far from home,” Idrissi Kaitouni said.

Idrissi Kaitouni also mentioned Bill C-18’s influence on spreading awareness. When attempting to post a Canadian news article covering resources available to help those affected by the earthquake, her post was blocked by Instagram. The MSU reverted to posting donation links instead, which has been successful.

Emphasizing the importance of donating to international initiatives such as Banque Alimentaire, Idrissi Kaitouni added their link to MSU’s Instagram bio.

“I know as time will pass, less people will be talking about [the earthquake]…But Morocco will need lots of time to heal from it,” she said.

Hafiz searched for a Morocco student club prior to the earthquake. She is grateful to see the MSU forming in support of her community.

“It’s incredible because everybody is rallying behind [us]. We saw it with the World Cup and now we saw it when it really mattered, when people needed it. I feel very, very proud to be from a country that can do that any day,” said Hafiz.