The importance of taking part in the future of Holocaust education

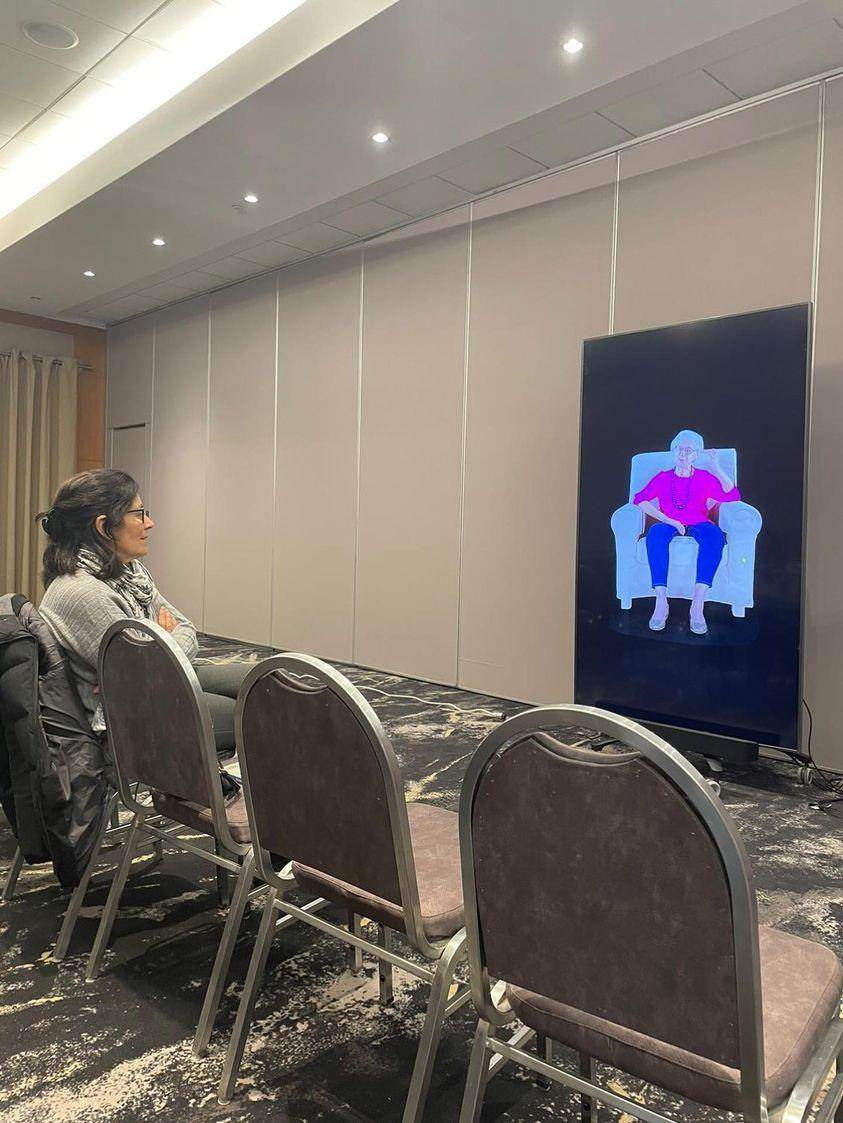

Attendees gathered at the Montreal Holocaust Museum (MHM) to test out the latest Dimensions in Testimony (DIT) exhibit, which allows one to have an almost real-life first-person interaction with a Holocaust survivor via pre-recorded video responses.

The test exhibit, based on survivor Marguerite Élias Quddus, features a francophone interactive biography that enables conversation through a 2D interactive display.

On Feb. 12, the museum held three free, one-hour sessions which took place from 11:30 a.m. to 2:30 p.m.

Camille Charbonneau, the museum mediator of the session, shared the initiative’s hopes in gathering over 8,000 interactions with Quddus over the next six months, to ensure the project’s accuracy.

“It’s very important to give a voice to the people that we still have with us today,” she said.

The University of Southern California’s Shoah Foundation, an institute for visual history and education, developed the DIT project in 2010, gathering over 55,000 video testimonies of Holocaust survivors and witnesses.

They partnered with the MHM and the Canadian Museum for Human Rights to bring their very first French-speaking survivor testimony to life and to preserve Quddus’ story of resilience.

Quddus was born in December 1936 in Paris, France. After Germany’s occupation of France in 1940, the four-year-old and her family found themselves affected by the antisemitic ruling of the Nazis and the Vichy Regime.

In 1942, her father was murdered in Auschwitz. Quddus and her sister were separated from their mother, where they spent three years hiding in convents and farms, under false identities.

The two sisters reunited with their mother after Liberation. Quddus has resided in Canada since 1967 and has devoted the last decade to speaking with thousands of students to help bring Holocaust education to future generations.

In 2013, she published and illustrated her novel, In Hiding, which is her memoir of the Holocaust.

MHM executives took part in a five-day real-life question period with Quddus. The team recorded over thousands of interactions with the survivor. Quddus’ pre-recorded responses are in the present beta testing display.

Charbonneau felt touched after hearing some of Quddus’ earliest childhood memories.

“She was a child,” said Charbonneau. “She was five years old, and she had to stay in those convents with nuns… She needed to change her complete identity and religion to fit into this mold, to be considered a non-Jewish kid. She had to hide herself. That can be very traumatic for a child.”

Claire Berger is a volunteer tour guide at the MHM and a second-generation Holocaust survivor. Her father, Emil Berger, was born in Chernivtsi, Romania, and lived in a Ghetto.

“He remembers living in the ghetto, of course, and being hidden on a farm for six months, which saved him from being deported,” she said.

Berger enjoyed the humane, relatable aspect of conversing with Quddus.

“I love these spunky sort of retorts. I think it humanizes the fact that, you know… that they were children, just as we are,” said Berger.

As a former educator, Berger strongly believes in educating today’s younger generations about the Holocaust, especially in ways that make the most of technology.

Berger plans to take part in the future of Quddus’ interactive display, in the hopes of sharing more survivor stories, like her father’s.

“My dad passed away 18 years ago and every week now we’re seeing in the paper all of our survivors who are aging… I feel like doing my bit to keep the memory going as much as I can,”

Berger Said.

The MHM’s beta testing of DIT is free and takes place at the museum, on the first and second Sunday of every month until July 2023. With the assistance of an animator, attendees are welcomed to ask Quddus questions at the session.