Concordia’s Greenhouse hosts a project inspired by a utopian concept, to be presented April 22

After making your way up to the 13th floor of the Hall Building and passing through an inviting doorway, you might suddenly notice the smell of fresh soil as hoses on a “mist” setting crowd your sinuses. An overwhelming presence of life makes itself known; a sort of hidden life, perhaps.

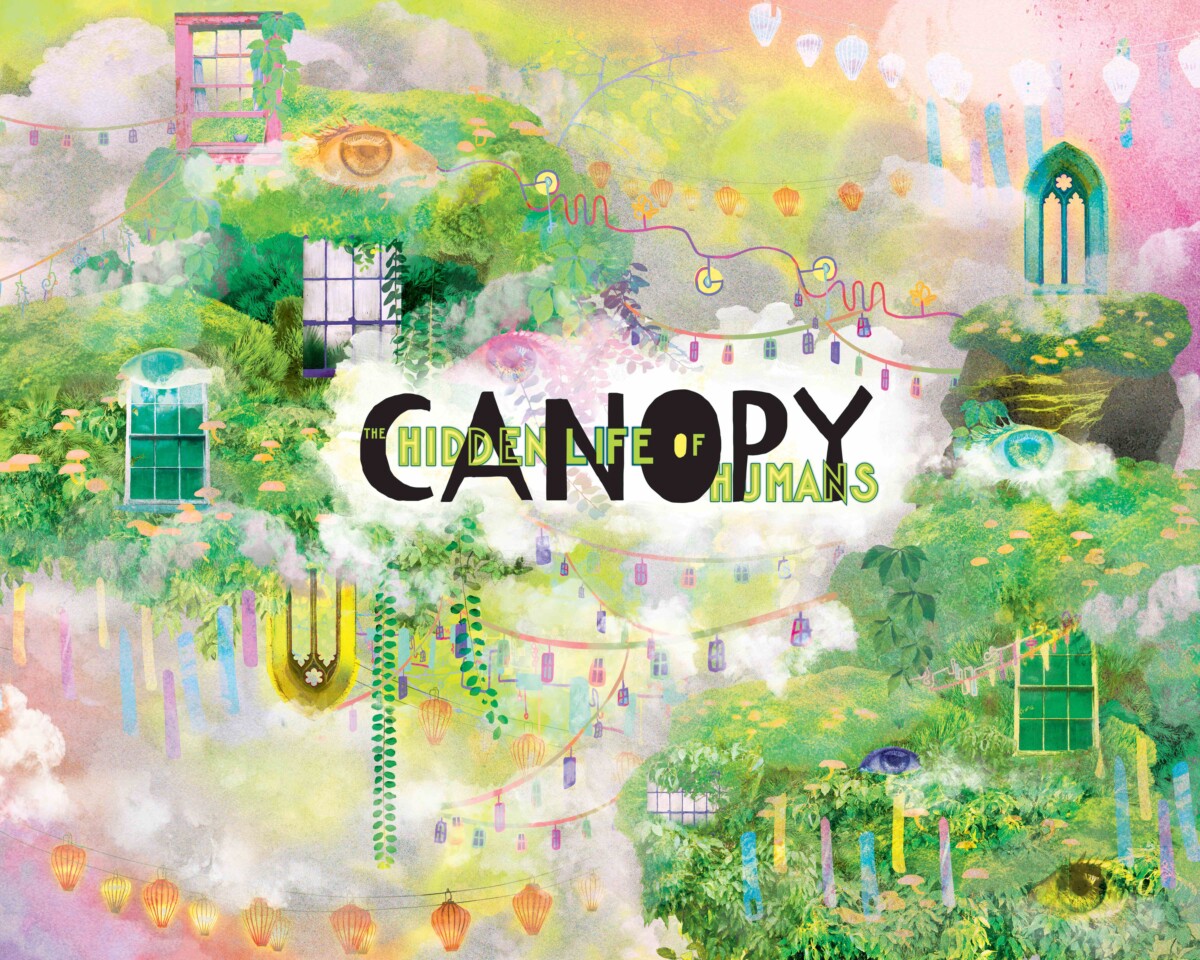

You’ve stumbled upon Canopy; The Hidden Life of Humans: a project that unites science with arts and crafts in pursuit of the idea that we, as humans, may one day be able to move civilization above the ground into canopies.

Maddy Schmidt, who recently graduated from Concordia with a major in design, conceived the idea in August of last year while walking through Montreal and spotting a planter erupting with vines and other vegetation.

At the same time, Schmidt was listening to a Radiolab podcast about copepods: small crustaceans found in various aquatic habitats, and even in above-ground ecosystems among trees. In their episode Forests On Forests, Radiolab states that about 50 per cent of all terrestrial beings live in trees.

“I saw this crazy web of vines, and they were all linking onto each other. It looks like they’re holding each other. I saw them linking onto the fence,” said Schmidt. “I saw them linking onto other plants. And I was like, there’s this completely interconnected world, it was so mind-blowing.”

The Canopy co-creator immediately called her longtime friend, first-year photography major Liliane Junod, out of inspiration. The “partners in vine” brainstormed ideas for a project honouring the concept of humans living from the top down, rather than the ground up.

The idea of the project is to hang all sorts of house plants, such as pothos, also known as devil’s ivy, around the Hall Building’s greenhouse. They would be linked together with grapevines and hung on trellising made from recycled materials.

The Canopy team is gathering material from Facebook groups that are designated for sharing recycled materials, such as Creative Re-use: Ø Waste, or CRØW.

Canopy will be hosting a workshop in collaboration with Concordia Precious Plastic Project (CP3) and Concordia University’s Centre for Creative Reuse (CUCCR), on April 4 from 9 a.m. to 11 a.m.. Anyone is welcome to attend.

CP3’s portion of the workshop will entail drawing lantern designs and learning how to transform them into illustrator outlines, which will then be cut into recycled plastic sheets with laser-cutters.

The second part of the workshop, led by CUCCR, will focus on making arts and crafts with recycled materials, and techniques such as sculpting, drawing, painting, and printing will be taught by Concordia’s fine arts students.

“The end result of this project is going to be an exhibition where we create this magical canopy space in the greenhouse, and we’re going to include our artists from the community,” said Junod. “We’re excited to have not just people in fine arts, for whom art is their entire life, but also anybody. So we want to put forth the message that everyone can create for this.”

One of the Canopy team’s keywords is optimism, and their goal is to keep the community lighthearted when thinking about the environment.

“We really want this project to be as uplifting as possible,” says Schmidt. “Of course, we’re addressing tons of systemic issues, methodologies, but we’re exposing them through something much more artistic and colourful.”

The Canopy team is calling on any students from the Fine Arts, Arts and Science and JMSB faculties who are willing to lend a hand between now and the day of exhibit on April 22.

You can visit the project’s Linktree @canopythloh for more information.