Anonymous co-creator speaks about how the page can validate student experiences

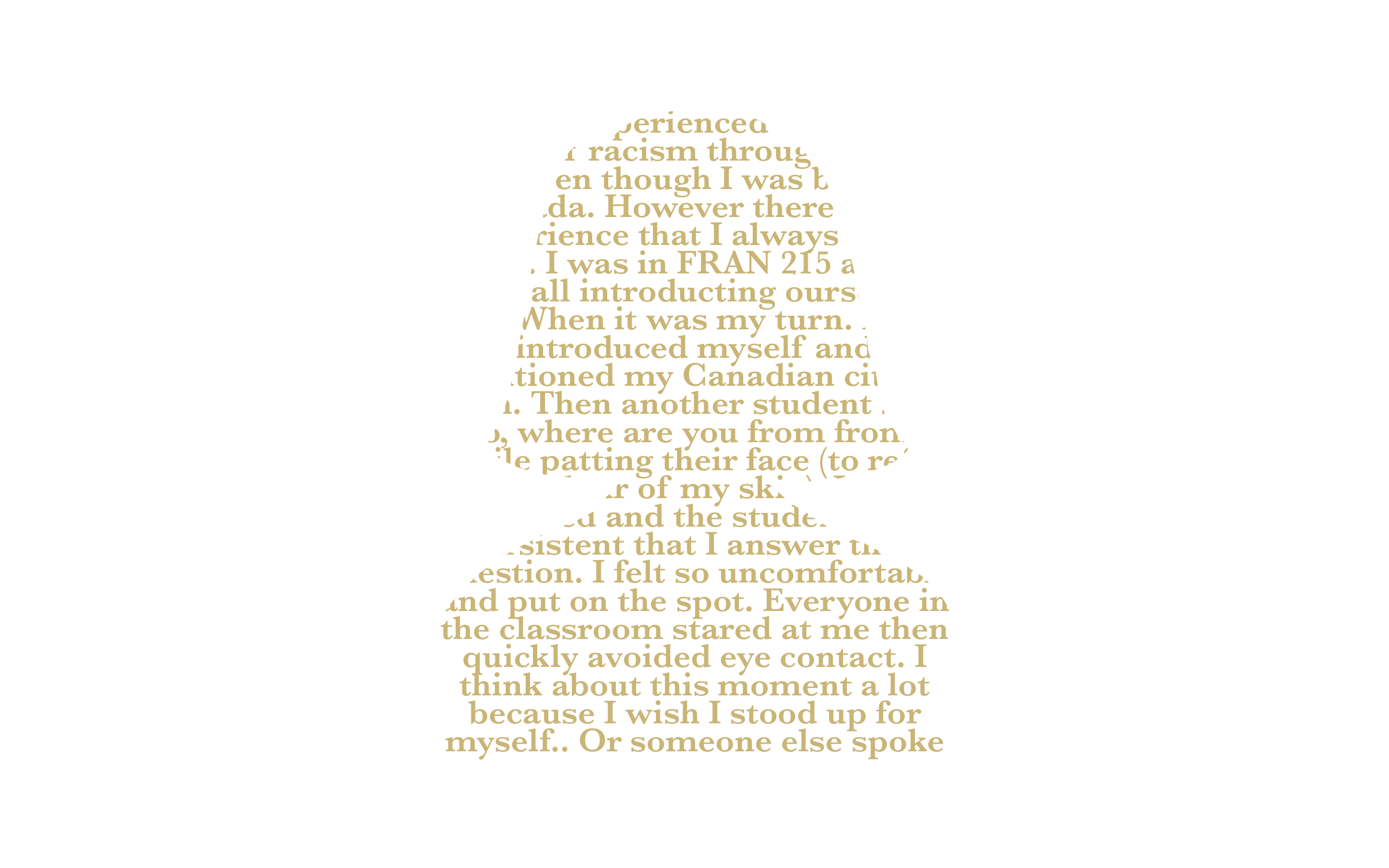

Untold Concordia is an Instagram page that features anonymous submissions detailing stories of oppression, such as racial, gender, and sexual discrimination by Concordia faculty members and student organizations.

One of the two creators behind the page agreed to speak with The Concordian under the condition of anonymity. They told us they started the page after seeing how popular the Untold McGill page became in early July.

“The [McGill] page was getting so much traction and so many people seemed to have a desire to have a space to share stories like this, [we thought] that was probably shared at Concordia, and we were right,” they said.

As the Black Lives Matter movement gained momentum in the early summer following the death of George Floyd, conversations revolving around discrimination came to the forefront. The goal stated on both Instagram pages is to highlight experiences of oppression and discrimination at the respective universities.

“Your experience is valid,” reads the first post. “Submit your stories and help create a platform for others to be heard.”

All posts are referred to as submissions rather than complaints. The co-creator told The Concordian the page is not affiliated with Concordia University and the submissions “aren’t complaints in any official capacity.”

One of the posts describes witnessing how a professor teaching a sexuality class did not use the right pronouns for one of their students; another describes being severely let down by the Concordia administrations’ handling of their sexual assault complaint.

Anyone can anonymously fill in a submission form by clicking the link in Untold Concordia’s bio. They can also choose if they prefer to keep the comments on or off on their post.

“We never ask them to reveal their names and we encourage them not to reveal the names of anyone involved … for their safety and our own,” said the co-creator.

“Some of these accusations can be relatively serious, and we want it to be truly up to the submitter if they do want to file formal complaints. They have the lee-way to do that without any of these submissions coming to hurt them in that process,” they said.

One of the issues with anonymity is determining the validity of the complaints. From the beginning, both creators discussed this issue and what to do if someone were to try trolling them.

So far, the posts have all been believable. Both creators are members of minority groups who have experienced “varying levels … of oppression and systemic oppression within the University and outside, and coming from that place, you can kind of tell.”

Because the account isn’t an official complaint forum, anonymous users can feel free to describe the experience according to their understanding.

“They’re not meant to be perfect, factual re-accounts of events that happened. They are people’s perspectives; they are all true in their own way.”

“I’ve never seen one that I’ve been like — I don’t believe that — every single one of them to me is truly believable,” they said.

The posts speak to the larger issues of discrimination.

“The university is a structure like every other built on centuries of oppression that is rooted in Canadian history and much of the world’s.”

They feel some of these posts don’t refer to instances of “active hate and active oppression, but they are people not realizing how harmful what they say is and how harmful what they’re doing is just because it feels normal to them.”

“A few of our posts have been around the subject of various professors using slurs in quotations or in discussions, and saying ‘since I’m referencing, quoting a text is allowed.’ Students who are directly affected by the slurs feel very uncomfortable.”

Just this week, University of Ottawa part-time professor Verushka Lieutenant-Duval was suspended and later apologized for using the N-word during an online lecture after a student made a formal complaint. Several professors and government officials are weighing in on this issue, with Legault denouncing backlash against the professor.

They said many submitters have thanked them for the page, especially as many submitters have tried to file formal complaints and it is difficult to get through.

Concordia Student Union (CSU) General Coordinator Isaiah Joyner said that the process of submitting a complaint against someone with the University can be challenging for students.

“The whole overall process [for complaints] is not student friendly, it’s more bureaucratic…it’s very rare that you see the effects yielding the result in the favour of what the students want.”

The co-creator of the account said they would like Concordia to realize students are turning to anonymous means to voice their concerns.

“Eventually, maybe, Concordia will kind of realize that there are so many students that feel uncomfortable reporting these instances and that these instances are more harmful than they think they are, [and] maybe take action for that.”

“For these young people who are for the first time stepping into their own, there needs to be ways for them to express how they feel and how they’ve been harmed that is more streamlined and … accessible,” they said.

Concordia Spokesperson Vannina Maestracci released a statement to The Concordian on Untold Concordia: “Although we understand that some prefer to use social media anonymously to be heard, we’d also encourage all members of our community, if they want, to take advantage of our internal accountability mechanisms so that we can properly address these issues.”

“Complaints brought through our mechanisms are treated confidentially and independently and can be addressed in a variety of ways, including with support services, depending on what a student wants.”

Graphic by Taylor Reddam