“Right now, we are not seeing a lot of positive Trudeau memes,” said Associate Professor Fenwick McKelvey. “So, will it influence the vote? That is something we walk in with an open mind, saying this could be totally meaningless. But then at the same time, it is an important part of how people understand and engage in politics.”

The lack of investigation of the role of memes in Canadian politics led McKelvey, from the Department of Communication Studies, to look at the content being shared on social media. While memes are usually regarded as harmless, humoristic tools, McKelvey argues that they are actually an important part of shaping public opinion and representing all the different political party leaders.

“I think the humour part is important because people look at these images and it helps them laugh or make a joke,” said McKelvey, “and then they identify closer with that party or with the people who created the joke.”

According to the research, which McKelvey is doing with the help of undergrad students, there is currently a tendency towards counter-Trudeau memes. And it is not only a right-wing phenomenon, but memes are also used by all parties to campaign with generic, negative messages.

The research identified 30 Facebook groups posting memes about the election, each focusing on different issues. It can be observed that from the left-wing, climate change is a recurring theme while the right promotes corruption-related memes. Yet, Trudeau’s various scandals, such as SNC-Lavalin and his Brownface incident, prevail above all.

On Sept. 27, in a meme-tweet style, Trudeau announced his latest environmental promise to plant 2 billion trees if he was to be re-elected. “We’ll plant 2 billion trees over the next ten years. That’s it. That’s the tweet.”

This tweet, which McKelvey argues was orchestrated by his campaign staff, was an attempt to adopt the meme trend and ended up backfiring on him. It was received more as a joke than anything, said McKelvey.

“It’s interesting to see the varying reactions, I mean at least from the students,” said McKelvey. “No one took it seriously. It came across as a joke.”

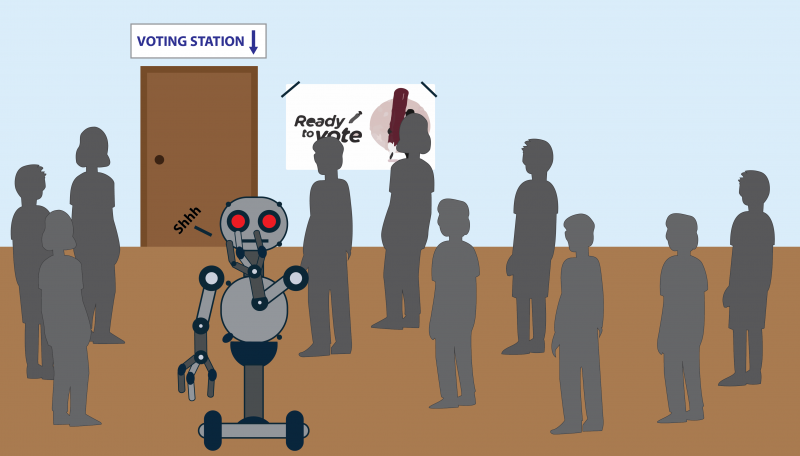

The research comes after McKelvey co-wrote a paper with Elizabeth Dubois on the role of bots in politics. Simply put, bots are the loose word to describe any automated accounts on social media that behave or pretend to be a human.

In politics, the worst scenario could be where bots push for a story to become more popular than it should be, whether false or not, impacting public perception directly. It can become terrifying knowing that, according to a study by the University of Southern California and Indiana University, nearly 50 million Twitter accounts are run by bot software.

Although, under the Transatlantic Commission on Election Integrity, political parties worldwide have now agreed to obey a code of conduct that states full disclosure on their use of bots.

Yet, while Jagmeet Singh and Andrew Scheer took the pledge, neither Justin Trudeau, Elizabeth May nor Maxime Bernier’s names can be found in the online agreement.

What about their roles in spreading false information?

Since the 2016 United States election, the existence of online-interferences from automated agents is not a secret anymore.

In fact, parts of McKelvey’s research on the role of bots was to recognize the capacity of bots to manipulate the content on social media, but also acknowledging that bots can serve important public functions, along with the public interest.

“We have the CBC using bots to help people understand how disinformation spreads online,” said McKelvey. “We also have a bot that is called the Parity Bot. So, whenever someone tweets something negative or abusive to a woman in politics, it will automatically tweet something positive. It’s a way to counter interact negativity online.”

And when it comes to memes, McKelvey argues that analyzing false information being spread through them doesn’t look at how people share information they know to be false but believe anyway. Instead, he believes in trying to think about this sharing process more as social identification; how people come to understand themselves and politics.

Graphic by Victoria Blair