Exploring the role memes play in our everyday life

No matter where you look online, memes will appear somewhere. From the most quotable movie lines to funny and controversial moments, nearly everything can be turned into a meme. But, can memes be considered art? And are memes some kind of insight into the truth about how the public truly feels about relevant topics in society?

Why do people love memes so much? According to digital marketing agency and web developers SEO Shark’s website, people tend to gravitate toward using and interacting with memes because they’re “easy to share, they’re funny, audiences relate to them and … they are topical and timely.” These reasons make memes a nearly essential part of how people interact with the world around them.

The ease of sharing memes is such a selling point because in today’s society, the quicker we access things, the higher the likelihood we will interact with it. Also, it creates a sense of connection because we can freely share memes with whomever we choose. The humour is also another element that lends itself well to meme interaction. A lot of the time, we want something that will make us laugh, and memes do that easily. So, it becomes a way for us to get that enjoyment that we crave.

When it comes to memes being topical and timely, this touches on whether or not they can be a source of truth. Often, there is a mocking tone, reminiscent of the fools in Shakespeare’s plays. The fool or the jester was able to make relevant critiques without having to face the consequences of it because they are humorous. In many ways, memes tend to play the same role. They are calling out something relevant in society, but people tend to take them in a tongue-in-cheek fashion, yet the commentary the meme is making is still impactful.

Memes are a visual medium, which begs the question as to whether or not memes can be considered art. In many ways, the answer is dependent on how one chooses to define art.

I asked the members of a private facebook group called ‘90 Day Fiancé TV Show Uncensored,’ “Do you think memes should be seen as art?” 81 per cent of respondents said no. This outcome is not surprising as memes can be seen as lesser because anyone can make them. Also, people tend to associate the term art with a lot of skill. In many ways, memes can be seen as fun, but not that they take the same skill as an artist doing a painting. However, if art is being defined as a form of creative expression, then memes would absolutely be seen as art. Perhaps, through the ways memes are being used, the way we define art might expand to include this medium.

2020 has been a difficult year to say the least, and many memes have made a presence that discuss the year we are living in.

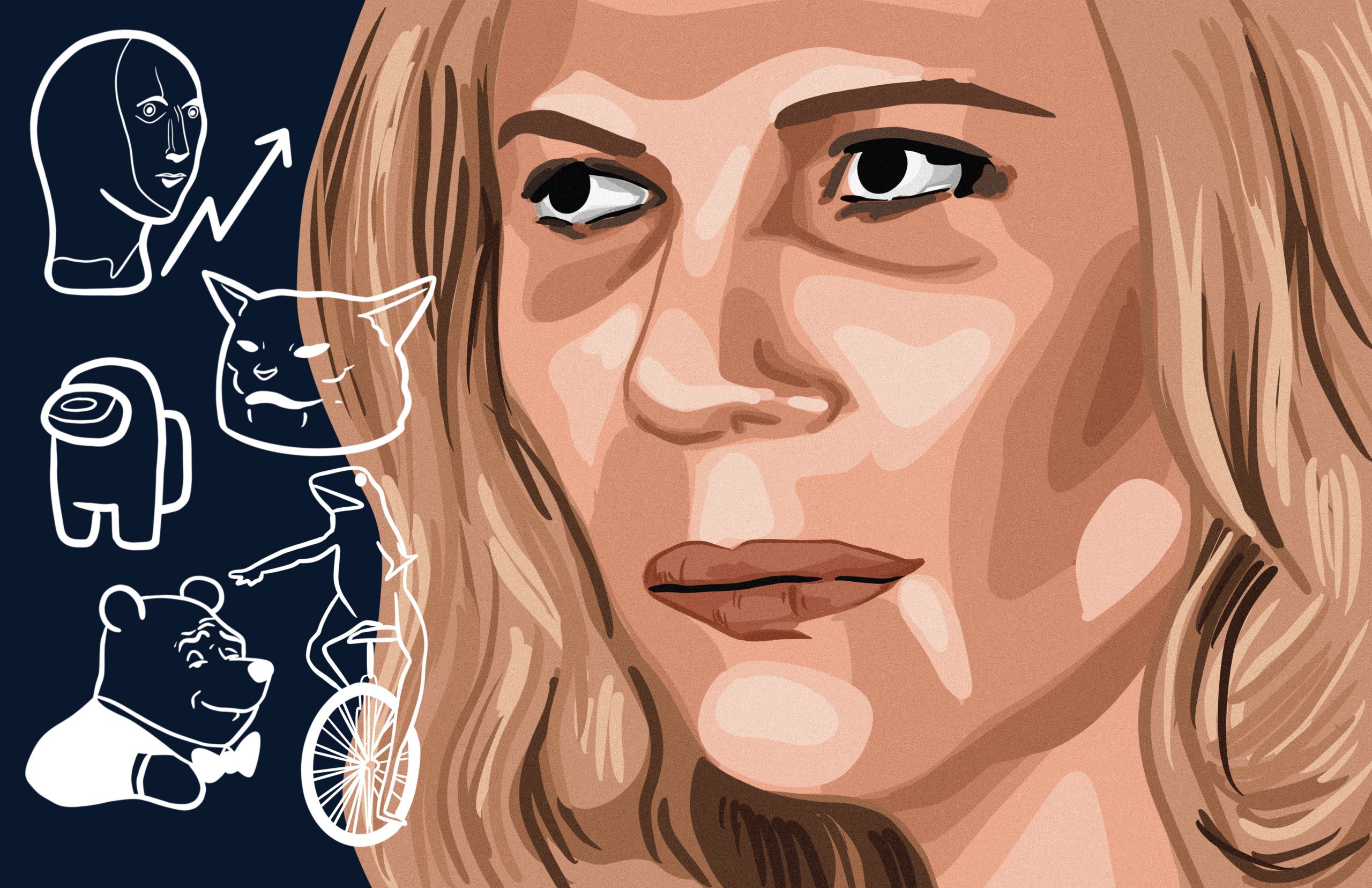

This meme, which discusses how 2020 will be perceived in the future, is an amalgamation of many older, popular memes. Aside from being humorous, it allows people to remember what made us laugh so often in the past. In many ways, it seems like 2020 has been a never ending cycle of stuff happening. This meme casts light on all of that, making it relevant.

Memes can also serve as a form of political commentary. During this year’s American presidential debate, there was a lot of talk about who has been making money off Russia. The debate in general was a bit of a mess, and this meme, featuring Spider-Man pointing to himself, captures the back and forth perfectly. This Spider-Man meme has been used many times, in many instances, and to use it here highlights how versatile memes are. It also suggests, at least within the confines of this topic, that Biden and Trump are just mirrors of one another. This meme is calling out the political sphere in a way that reaches the masses.

Memes are such a staple in our culture. They are not going to go away because they stay relevant with the times. They are a social commentary on situations that have gone through the court of public opinion. In a lot of ways, memes can actually be an indication of what people deem as newsworthy.

Personally, I think that memes should be taken more seriously than they are. I think that their accessibility makes them undervalued, but I believe that is exactly why they should be seen as more. As someone who views art as ever changing, I think memes have a place in the art world. I look at memes daily, share them with my husband, and we laugh so much. During the time we are in, I think memes are especially relevant. We need access to various forms of entertainment and art, and perhaps memes are the best way to gain access to these things.

Whether you like memes or not, they aren’t going anywhere, and I think with time people will take them more seriously.

Graphic by @ariannasivira