Small talk, chitchat, pleasantries — whatever you want to call it — looks different nowadays

Small talk, the light conversation you have in social situations, is a ritual best known for its uncontroversial politeness. Yes, the social situations where small talk comes up are long gone, but that’s not the only reason small talk looks different in 2021.

Say you mention the weather: “It’s unseasonably warm this spring!” One might just as well respond with the facts: “Yes, well, permafrost in the arctic is melting, releasing the powerful greenhouse gas, methane, into the atmosphere. This creates a feedback loop, where the methane that’s released further warms the earth, which then melts permafrost quicker, which further releases long-stored methane, in an unstoppable loop we call climate change. But it’s perfect scarf weather.”

See how weather is a no-no?

“How’s the family?” This, while a valiant effort, is still too dangerous: “Well, my parents haven’t seen a soul beyond each other in a year, leaving them in total psychological ruin.”

“How are things?” “I’m anxious and depressed, but for no obvious reason. I have a consistent routine, a big circle of friends, I exercise, I eat well, and I sleep eight hours a night. Despite all this, something still feels deeply wrong — like a yawning chasm — in my core. You?”

What about a simple one? Talk about friends in common. Gossip, at least, should preserve through a pandemic, no? “Have you spoken to so-and-so lately? I haven’t heard from her in ages!” It should be safe, unless your friend is critical of toxic monogamy culture and the pressure cooker it’s been put in with COVID-19 isolation, responding, “That doesn’t surprise me. She moved in with her COVID boyfriend and they only see each other. It can get toxic pretty fast in those conditions. I read that domestic violence is at an all-time high in Quebec. Eight Quebec women murdered in eight weeks.”

So, “girl talk” is out.

“Have you been reading the news? This COVID thing is really wild, eh?” That could work! Right? Wrong! “Oh yes! Last week there were more than 25 deaths reported due to COVID in Quebec!”

Local news is out as well.

How about national news? Nope — the toxic waste storage and handling in B.C. reads like a pamphlet on how to be evil.

Continental? Nope — the trial of George Floyd — I mean Derek Chauvin — that highlights Floyd’s substance use as a key defense for Chauvin’s murder charges says everything you need to know about access to dignity, justice, and peace for Black Americans, and comparably, Black Canadians.

International? Nope — around the world, school-age children are out of school. Even in societies capable of creating homeschooling alternatives, children are dropping out of school. These educational barriers pose the greatest risk for youth already made vulnerable by marginalizing structures during a formative time in their cognitive development.

We can search and search to find something light to talk about. Or, we can all agree that small talk in 2021 is dead.

We can create joy and meaning in the tangible things going on moment to moment, like hearing birds sing or feeling the sun on our faces. And we can let ourselves cry when faced with the oversaturation of information, the thinning potency of entertainment, those reprehensible systems of governance, and the aloneness of individualistic thinking.

We can spend more time developing communication skills, cultivating curiosity about ourselves and others, and creating space for compassion and nuance in the human experience. There’s nothing light to talk about in 2021. So, instead of pretending that spring came early this year, let’s face the facts, and find wellbeing despite the reality. Let’s be honest about the circumstances, heavy as they may be, and plant roots in tangible sources of joy.

Don’t know where to start? Read fiction, create art, learn an instrument, practice another language, be present in the moment, take slow breaths, ask people real questions, observe animals, speak your piece and your peace, pause and think before reacting to things, massage your feet, name your feelings, make people laugh, let yourself cry, let yourself laugh.

And please, I beg you, stop making small talk.

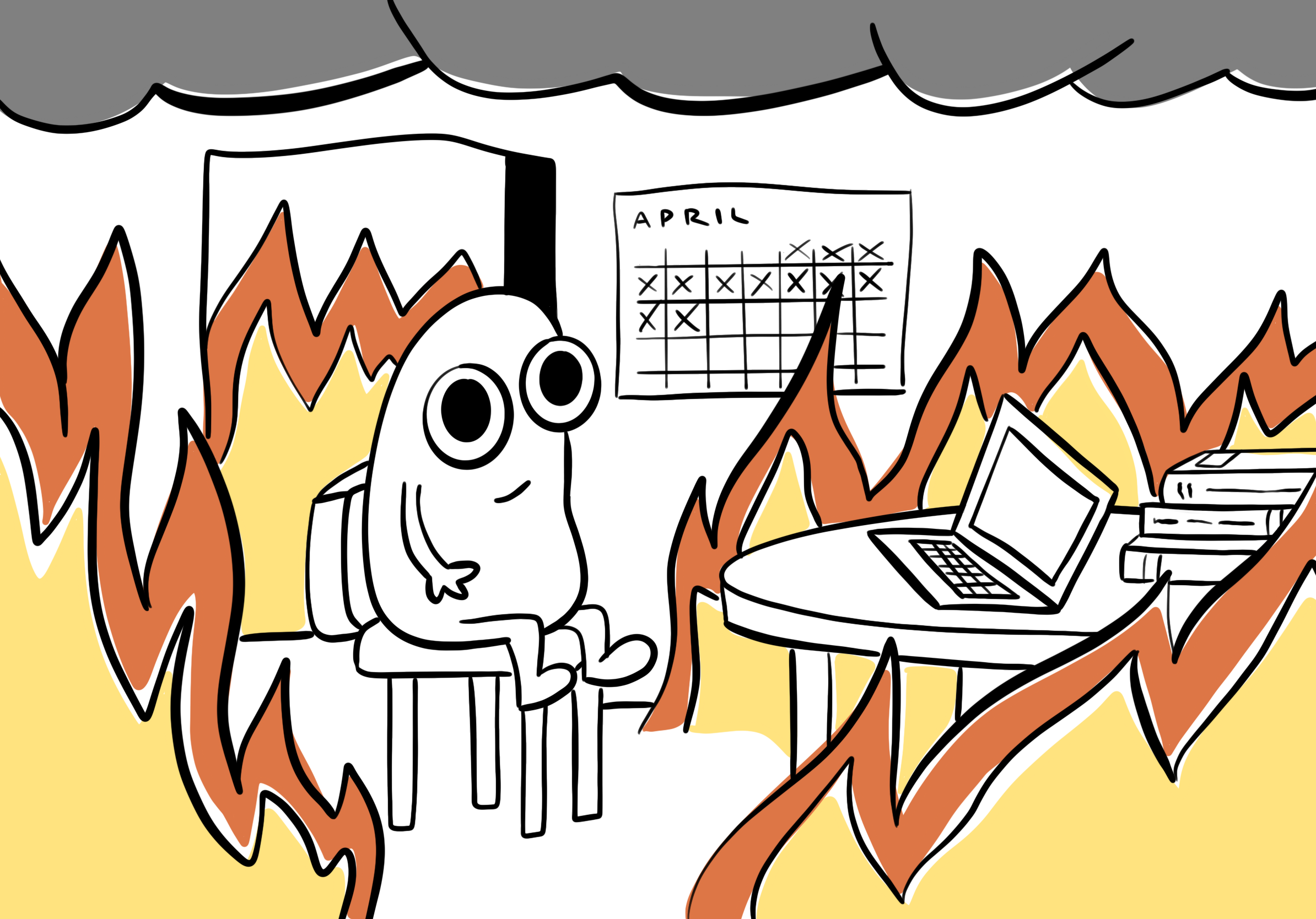

Feature graphic by @the.beta.lab