After a negative experience with SARC, Concordia student decided to turn to his Indigenous roots to heal.

After Salim, a former Concordia student, dropped out of school following his negative experience with the Sexual Assault and Resource Centre (SARC), he wanted to heal. He decided to escape from what he knew about healing to finally find peace. For anonymity purposes, The Concordian is only using his first name.

Before his life changed, Salim was a history student and a member of the Concordia University Catholic Student Association (CUCSA). He had friends in the association, but when he came out to them as gay, “they rejected [him] entirely,” he said.

When he told his other friends what had happened, they were not as supportive as he hoped. Several stayed by his side, but for the most part, it was a long and winding road back to a better place.

“I don’t feel that the religious clubs are really prepared yet—not only for 2SLGBTQ+ issues, but also sexual assault issues,” said Salim.

On Jan. 29, Salim was raped by a non-student off-campus. The experience traumatized him, and he went to the SARC for help.

During his first session, he told his counsellor about this incident and that he was having passive suicidal thoughts. Even though Salim was clear about The counsellor, Salim said, had a “look of panic on her face.”

“She was calling a lot of people and I was like, ‘Okay, I’m not getting out of this session on my own.’ I was frozen because I just couldn’t do anything,” said Salim. “This was out of my control already. I didn’t have any say in what happened next. It was really tough. I got escorted to an ambulance by the Concordia security guard in front of everybody. The whole campus saw me. It was really, really embarrassing.”

The ambulance drove him to Jean-Talon hospital. He was left alone in the waiting room, so he decided to leave and go home.

“I didn’t think anything else was going to happen,” said Salim.

But when he arrived home, two police officers were waiting inside beside his parents. They told him that he had to go back to Jean-Talon hospital.

He arrived at the hospital and was locked in a room. There were no windows and no pillows, and he was forbidden from using his phone. The only thing in the room was a small bed with a seat belt. Salim was put on suicide watch, and became completely cut off from the world.

He was locked in that room for 16 hours before seeing a psychiatrist. During that time, a nurse only checked up on him once.

“I think it was my normal reaction to just scream and kick the door so they could let me out. I never thought I would be in that kind of situation in my life,” said Salim.

He recalled that most people in the emergency room were minorities. Salim is a descendant of the Quechua nation, from the Andes mountains of South America.

As an Indigenous man, he witnessed how different the treatment was towards minority groups in hospital facilities. After being sent to the hospital a second time, Salim went back to SARC for another session. He was still struggling and confessed that he was having suicidal thoughts. The counsellor had the same panicked reaction as before.

He recalled that she got frustrated with him regarding how much time had passed since he got raped. She asked him, “It’s already been a few months, you should be over it by now. Why are you still sad?”

“The incompetence I felt, the helplessness I felt—I was basically left alone. Mostly what [SARC] does, if anything, they will send you an email: ‘Are you alright? How are you doing?’ And that’s it,” said Salim. “Basically, they won’t do anything else unless you tell them to do so.”

SARC was the only resource Salim knew about. The centre he thought would help him did the complete opposite. He does not know if the treatment from SARC is different for Indigenous students. He is concerned for these students that they may not get the treatment they deserve.

The Concordian reached out to SARC for an interview but has not heard back.

“I don’t know for Indigenous students, if the process is different on their centre that they have, but I can’t imagine if there’s an Indigenous student who faces sexual assault, what kind of help they’re going to get,” said Salim. “It’s going to be even worse for them going to SARC, because I don’t think they [SARC] are trained in Indigenous visions of health and healing.”

Salim realized that Western medicine was not the cure for his trauma. No amount of medication was going to dial down the traumatic symptoms he was feeling.

“The whole psychiatric and psychological modern institution that we have is also rooted in colonial investigation and colonial visions of what is health, what is illness,” he said.

He decided to explore the roots of his Quechua ancestors and reconnect with his culture. Salim realized that he needed to shed what he knew about healing and modern science, and tune into himself to heal.

“I think that decolonizing myself also told me that, you know, that nature is with me and that I’m part of this whole entire thing [existence]. So nature healed me,” said Salim.

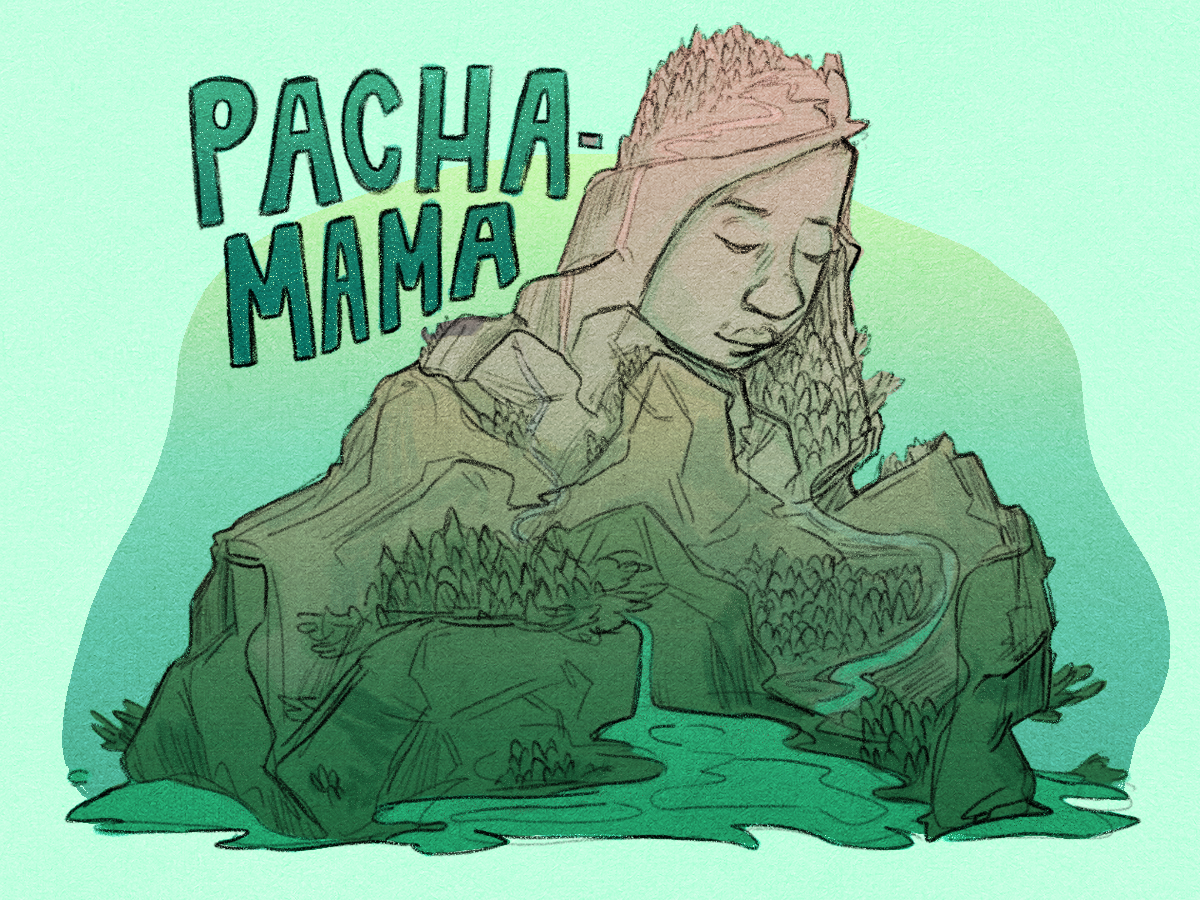

“It was something necessary for me. It’s unfortunate that it had to happen this way, but in the end, I’m very thankful that Mother Nature, Pachamama, as we call Mother Earth, took me back in her arms.”

Salim “remembered the knowledge his ancestors gave him”, by simply being present with nature, going to the park, and feeling its beauty. He recalls facing the sun, and acknowledging the heat he received from “his father, the sun, Tata Inti in Quechua, hugging him with his light.

“Now, I look at [Tata Inti] and see “oh dad, there you are,” said Salim.

As he looks at the trees, he acknowledges them that they are his brothers. As he sits on the grass, he is sitting on his mother, Pachamama’s, lap and she welcomes him home, letting him know he is safe.