The CSU criticized the university’s limited deadline and consultation process with student associations

Concordia University removed the due date for community feedback on their Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) plan after a Concordia Student Union (CSU) press release deplored the university’s limited time span for outsider input.

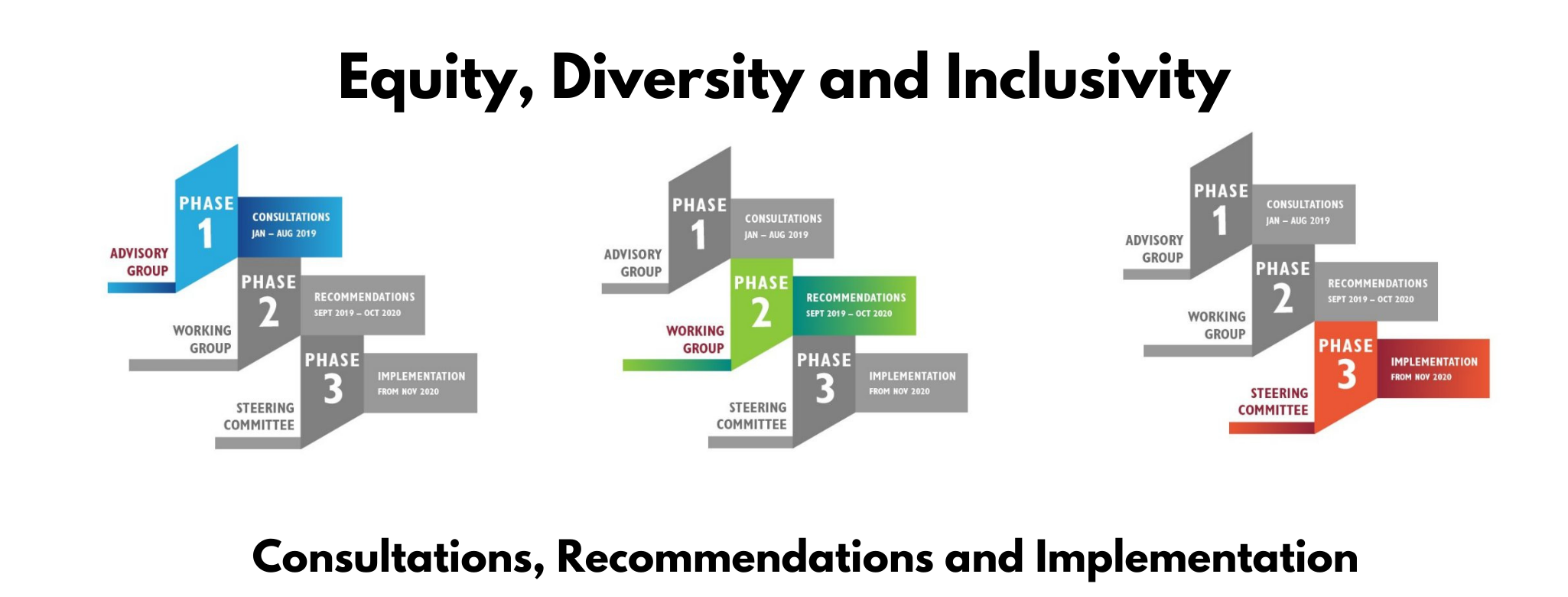

The EDI plan is a three-phase process that is aimed at implementing equitable hiring practices, increasing diversity, and fostering an inclusive environment on campus.

Phase two of the EDI plan ran from Sept. 2019 to Oct. 2020, culminating in a 32-page report recommending how the plan should be implemented. The report was published by the EDI Working Group, a group mostly consisting of Concordia staff members.

The Working Group released the report for community input on Sept. 10, as part of the last step in phase two before proceeding to the third phase in November.

Initially the university gave a 10-day limit for community input on the recommendations made by the Working Group. This was planned to run from Sept. 10 to 20, which the CSU called an “exclusionary and flawed process.”

“There has been little publicity on this important process,” read the release, published on Sept. 16.

According to Concordia University spokesperson Vannina Maestracci, the deadline was removed around Sept. 17.

Following the press release, the CSU met with Lisa Ostiguy, Chair of the Advisory Group on EDI and Special Advisor to the Provost on Campus Life.

Ostiguy said the intention behind the limited deadline was not to limit feedback, but had to do with the pre-set due date of the EDI’s plan, which is next month.

She said she heard the CSU’s concerns with the EDI plan and process during their meeting together. She said, “we would continue to welcome any feedback, and if the Working Group finalizes their work, it doesn’t mean that the feedback would be lost.”

Any input on the EDI made after the report is complete would be passed along to the third-phase steering committee.

Ostiguy said the university did include student associations’ input throughout the EDI process.

During the second phase, over 40 student groups were contacted by the Working Group and invited to a three-step consultation process in August, which included a video-call information session, a questionnaire, and small group consultation sessions from Aug. 13 to 26.

She also mentioned that Kajol Pasha, a CSU student representative, was a part of the EDI phase one’s Advisory Group and phase two’s Working Group. Both groups had other students in the members list as well.

But according to the CSU and the CSU Legal Information Clinic, more needed to be done to include feedback from student associations.

General Coordinator of the CSU Isaiah Joyner told The Concordian he felt it was problematic that the CSU and other student associations were not heavily involved in the consultation process for the EDI plan.

Joyner said the Working Group did not reach out in a substantial way to centres like the CSU Student Advocacy Centre and the Legal Information Clinic, which “deal with these issues [of racism and discrimination] on the front lines.”

Walter Chi-yan Tom, manager at the Legal Information Clinic, said he is a “frontline worker” in helping students and faculty with issues relating to racism and discrimination.

Tom told The Concordian that the majority of the discrimination complaints he deals with are made by university employees on issues they face in the university workplace.

“Thousands of files we have gone through over the past ten years, they don’t even see that we are important enough to be interviewed as a stakeholder?”

The Legal Information Clinic was not included in the list of 40 student groups that were invited to the three-step consultation process in August.

He says throughout the entire EDI process there was minimal contact to get his input, or for any student associations’ input, compared to the input faculty had on the plan.

Last year’s Advisory Group report states that student associations were “contacted” for input; Tom said what the Advisory Group’s report means by “contacted” is that an email was sent.

“Bottom line, there wasn’t any real consultation or communication,” said Tom.

As the EDI moves into its third-phase — implementation — Tom questioned the report’s general recommendations.

“They are more recommendations on the principles, not necessarily the specific measure[s] for implementation.”

The CSU’s press release listed what they see as “serious flaws” in the Working Group’s report, including no reference to Quebec’s Act of respecting equal access to employment in public bodies, “which requires, among other things, Concordia, like all other universities, to identify and remove systemic barriers to equitable representation of women, Indigenous people, visible minorities, ethnic minorities and people with disabilities in different job categories.”

The press release also stated “that a quick search of the term ‘systemic racism’ or ‘systemic discrimination’ in the report produces no results.”

However, on the report it does state, “We commit to dismantling systemic historic and continued discrimination and inequities at Concordia University.”

In a statement to The Concordian, Maestracci said, “Over the two years, the extensive community consultation opportunities included a survey completed by 700 students, information sessions and six days of consultations in small groups as recently as this August and which included students.”

“The opportunities to take part in the EDI conversation were communicated widely to the Concordia community,” said Maestracci.

Visuals courtesy of Concordia University