Some Concordia students now consider leaving their car at home

Montreal gas prices have reached an all-time high, costing drivers up to $1.58 per litre. As the demand for driving has grown in the past few months, along with increases in crude oil prices, the gradual return to normalcy has entailed more expensive gasoline.

On Jan. 1, one barrel of Western Canadian Select (WCS) oil cost about $41.70, which then skyrocketed to nearly $76.90 by Nov. 5 — representing an 84.4 per cent increase in less than one year. However, Moshe Lander, a senior lecturer of economics at Concordia University, told The Concordian that crude oil prices are not the only factor influencing this spike.

Moshe explained that, as global transportation continues to resume, the shipping and aviation industries are competing with Canadian drivers for the same resources and thus overall demand for gasoline has increased. In Quebec, there are additional oil transportation costs because gasoline is not produced locally, on top of the price of oil refining and federal and provincial taxes.

However, Lander noted that one should look at the bigger picture, and compare the situation with pre-pandemic prices instead.

“The fact is, gas prices have barely gone up at all. Pre-pandemic, gas was around $1.40 or $1.45 in most gas stations around Montreal. So add a couple years, inflationary pressures — it’s perfectly reasonable,” said Lander. “But if you’re comparing it to lockdowns, with no one going to work […] while gas was priced at $1 or less — this looks jarring.”

Nevertheless, current gasoline prices pose financial challenges for some Concordia students, who are used to driving to the Loyola campus on a regular basis. For Ora Bar, a third-year journalism student, driving is a necessity since she commutes to and from Chateauguay four times a week.

“Last time I had to refuel, it hurt,” said Bar. “I am now considering switching to buses, though it’d take me three times as long to get to university. This would create lots of anxiety for me since I’d have to leave very early to avoid being late.”

Bar estimates that her 20-kilometre commute from the South Shore would take up to one hour and 30 minutes. The five-dollar transit ride involves several transfers which Bar is afraid to miss due to low frequency on certain routes.

“We’re still students, it is expensive! I certainly hope the government considers more practical bus schedules and reduced fares,” Bar explained, saying that she is hoping to find a more affordable alternative to driving in November.

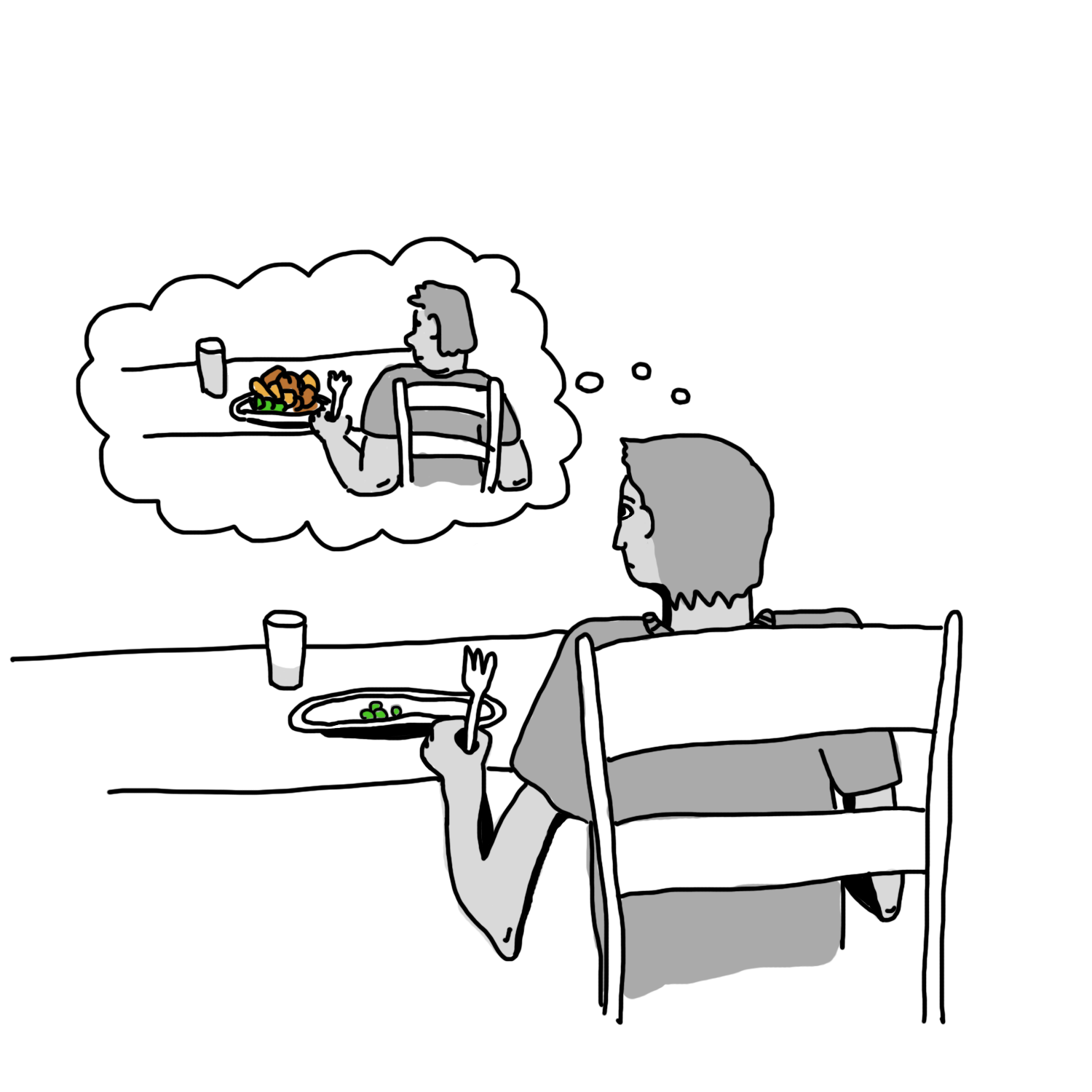

Meanwhile, Gabriela Serrano, a third-year neuroscience student at Concordia, has already decided to leave her vehicle at home for the foreseeable future.

“Because of the price increase, I can no longer drive to Loyola every single day. I realized that taking public transit is cheaper, coming from the downtown area,” she said. “But it was more convenient to drive than to take one bus, the metro, and then another bus — my commute to NDG is a bit more complex now.”

Serrano hopes the government will take action to avoid a surge in gas prices. “The pandemic was already a heavy burden for our economic situation, and now with simple things like driving to work becoming more expensive, it’s another stress,” she explained.

Gasoline, however, is already being heavily subsidized by the Canadian government. Last year, the country’s oil and gas sector received $18 billion in government financial support. In fact, Lander suggests that rising gas prices may lead to a turning point in North American car culture.

“That is a century in the past, we’re moving forward now. We have to price gasoline properly, […] at $5 a litre. As long as you continue to subsidize gas-fuelled automobiles, it’s making things worse — and it’s the hardest part for the consumer to understand,” he added.

Shifting such subsidies toward eco-friendly initiatives would help the city combat climate change. According to Lander, this would result in creating more pedestrian-friendly streets and cycling paths, limit Montreal’s urban sprawl, and make more funds available for efficient public transit.

The economist believes high petrol prices would push Montrealers to adopt electric vehicles at a faster rate. As fuel combustion makes the transportation industry responsible for 24 per cent of global CO2 emissions, rising gas prices could cause a shift towards a greener future, one driver at a time.

Photographs by Kaitlynn Rodney