What the disparity between the government’s promises of reconciliation and their actions means

It seems as though every time I tune into the news, there is a story of injustice involving Indigenous peoples in Canada.

From the original injustice of colonisation and residential schools to the increasing number of missing and murdered Indigenous women whose cases have only recently been looked into, there is a large gap of inequality between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians. Not to mention the housing crisis, high rate of suicide and the gap in the quality of healthcare and education, according to The Globe and Mail. Through all of that turmoil, one word shines through and gives me hope that the Canadian government wants to take positive steps to correct these wrongs. The word is reconciliation.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines this term as “the restoration of friendly relations.” The federal government seems to want to restore friendly relations with all Indigenous people, but in my opinion, the Canadian government and people still have a long way to go to achieve true reconciliation.

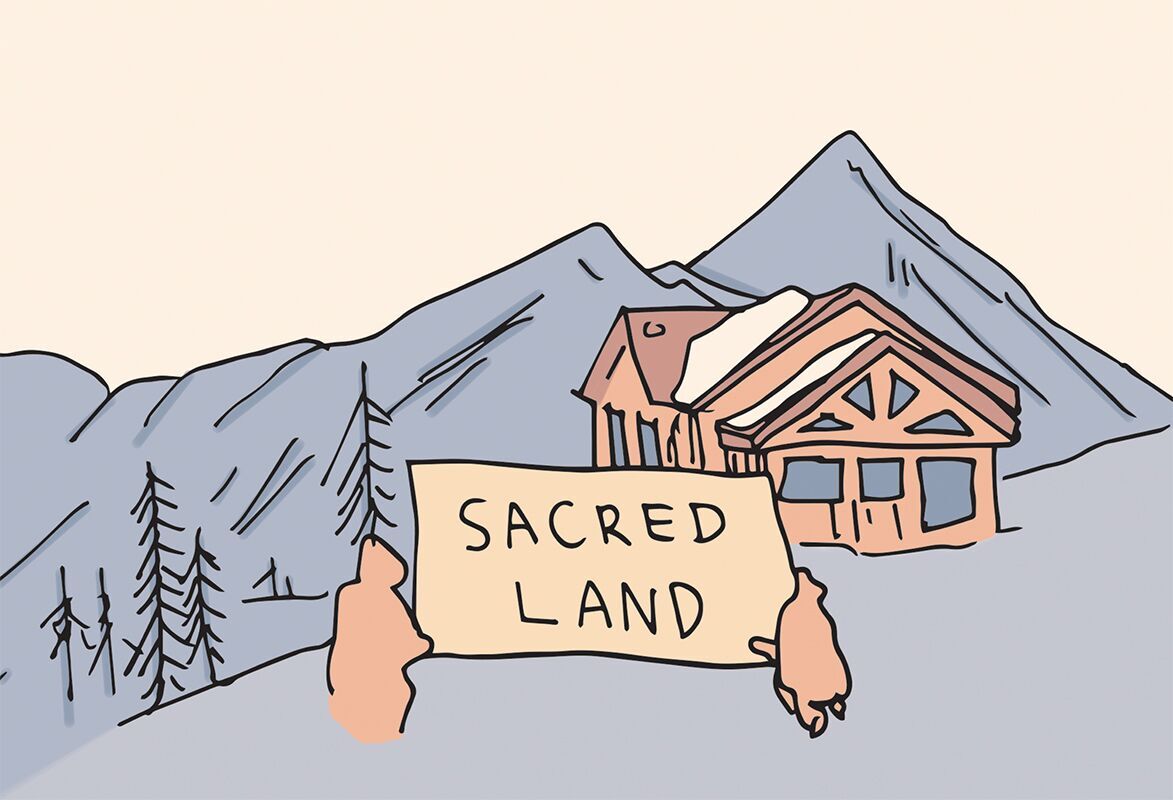

On Nov. 2, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that a Jumbo Glacier ski resort will be built on sacred land that belongs to the Ktunaxa Nation in British Columbia, according to The Globe and Mail. When asked about the situation, Kian Basso, a member of the Montagnais Nation, suggested: “The government should negotiate with the Ktunaxa Nation and try to figure out a way to meet in the middle.”

As an Indigenous person, he said he believes “it is only right that we respect the land and the people that were here before us. So I do not agree with the government taking this land because it does not belong to them, but I am not against the idea of building things on that land either. If they should build something, then it should be done with respect to the people living there and should be discussed between the two parties.” Basso’s statement refers to the lack of respect between Canada and Indigenous peoples—an issue that demands more discussion.

The Ktunaxa Nation has occupied the land in question for more than 10,000 years and use the land to worship their sacred grizzly bear spirit, according to CBC News. However, I believe it’s important to note that the Charter of Rights and Freedoms “protects the freedom to worship, but does not protect the spiritual focal point of worship.” This statement upsets me because it sets a double standard. I believe that if a church were to be torn down in order to build a ski resort, or any other luxury establishment, there would be public outrage. For the Ktunaxa Nation, their land is sacred to their culture and spiritual beliefs. I believe spirituality is equivalent to religion, so why are their beliefs not represented in the Canadian Charter?

Jill Goldberg, a specialist in Indigenous education, said, “When I heard the story, I thought, how is this even possible when we are in a time of improving relations?” She also pointed out the lack of representation in the Supreme Court. There is not one male or female Indigenous judge among the nine appointed judges. “If we want authentic reconciliation, we need to listen to them,” she added. “Let them lead the way, and let them participate. In short, true reconciliation cannot happen if we ignore those that are affected by the decisions.”

Realistically speaking, it isn’t surprising that the government places more importance on building entertainment establishments than respecting the wishes of a minority group. But when we see these stories emerge in the media, we should ask ourselves: when will Canada truly understand and take action against any and all types of injustice toward Indigenous peoples? When will we live in a country known for respecting not only the people inhabiting it, but their beliefs too? When will the value of words be strong enough to overcome any disparity between promises and actions?

Graphic by Zeze Le Lin